NZFFA Member Blogs

Member Blogs

-

Brian Cox's Blog

-

Chris Perley's Blog

-

Dean Satchell's blog

-

Denis Hocking's blog

-

Dennis Neilson's blog

-

Eric Cairn's Blog

-

Grant Hunters blog

-

Hamish Levack's Blog

-

Howard Moore's blog

-

Ian Brennon's blog

-

Ian Brown's Blog

-

Jeff Tombleson's blog

-

John Ellegard's blog

-

John Fairweather's blog

-

John Purey-Cust Ponders

-

Murray Grant's Blog

-

Nick Ledgard's Blog

-

Rik Deaton's Blog

-

Roger May's Blog

-

School of Forestry blog

-

Shem Kerr's blog

-

Vaughan Kearns blog

-

Wink Sutton's Blog

Recent blogs:

Timber Imports mean export of environmental impacts

Roger May's BlogWednesday, May 13, 2015

This article highlights trends in timber and timber product imports. It also addresses the implications for farmers and foresters growing special-purpose timber species and owners of sustainably managed indigenous forests.

BACKGROUND

Most New Zealanders love timber. We have used it for practical reasons and to satisfy decorative and cultural needs since people arrived here. Our forests and timber are woven tightly into our cultural heritage. At first, indigenous timber was all that was available but as shipping developed, this was complemented by imports of timber from Australia and North America. By the 1920’s, three quarters of New Zealand’s forests had been cleared and 90% of that was burnt, mainly for agriculture. Early last century, New Zealand began planting large areas of exotic plantations in response to predicted timber shortages and now has over 1.8 million hectares, primarily radiata pine (90%) and Douglas fir (9%).

Before the 1970’s, the ready availability of native timber for all sorts of purposes was taken for granted. This changed as the public’s environmental awareness grew and environmental organisations applied direct pressure on government to stop the ‘destruction’ of our indigenous forests. This pressure has resulted in a plethora of legislative changes reaching back decades which have directly affected the management of our indigenous forests and the availability of New Zealand indigenous timbers. These changes lead to the dis-establishment of the NZ Forest Service, the establishment of the Department of Conservation, the closure of Timberlands West Coast and controls on the harvesting of indigenous forest on private land via the Forests Act 1993. The Resource Management Act and the New Zealand Forest Accord effectively imposed additional constraints.

At the same time, radiata pine and Douglas fir became available and more accepted as structural timbers. With a wide range of basic uses, these two exotic timbers eventually removed the need for indigenous timbers to be used for such purposes. As a result of this, together with the pressures and the legislation, there has been a steady decline in timber production from New Zealand’s indigenous forests. The annual harvest of indigenous timber is currently under 20,000 m3.

Irrespective of the quantities available, radiata pine and Douglas fir clearly do not satisfy all the requirements of the New Zealand timber user. Special-purpose timbers are still highly sought after. With the production of special-purpose timber from our indigenous forest constrained by sustainability criteria and standards and lacking adequate resources of New Zealand-grown exotic special-purpose timbers, New Zealand consumers have transferred their environmental footprint off-shore by purchasing forest products imported from overseas. It is of fundamental importance that very few of these imports carry any reliable ‘sustainability’ credentials.

All graphs are based on MPI data. Year 2013 figures are provisional.

IMPORTED TIMBER PRODUCTS – Sawn Timber

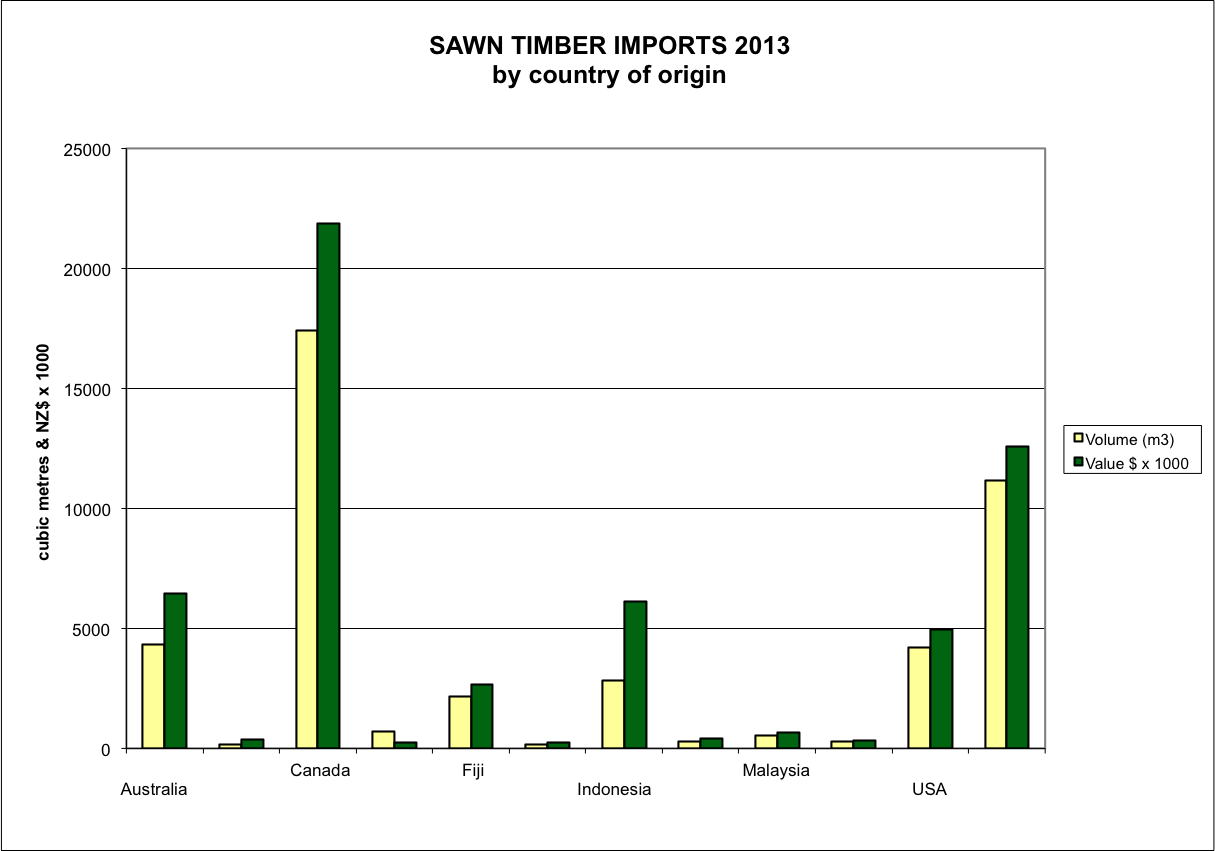

The graph below shows the volume and value of sawn timber imported into New Zealand from the main sources for the year ended June 2013.

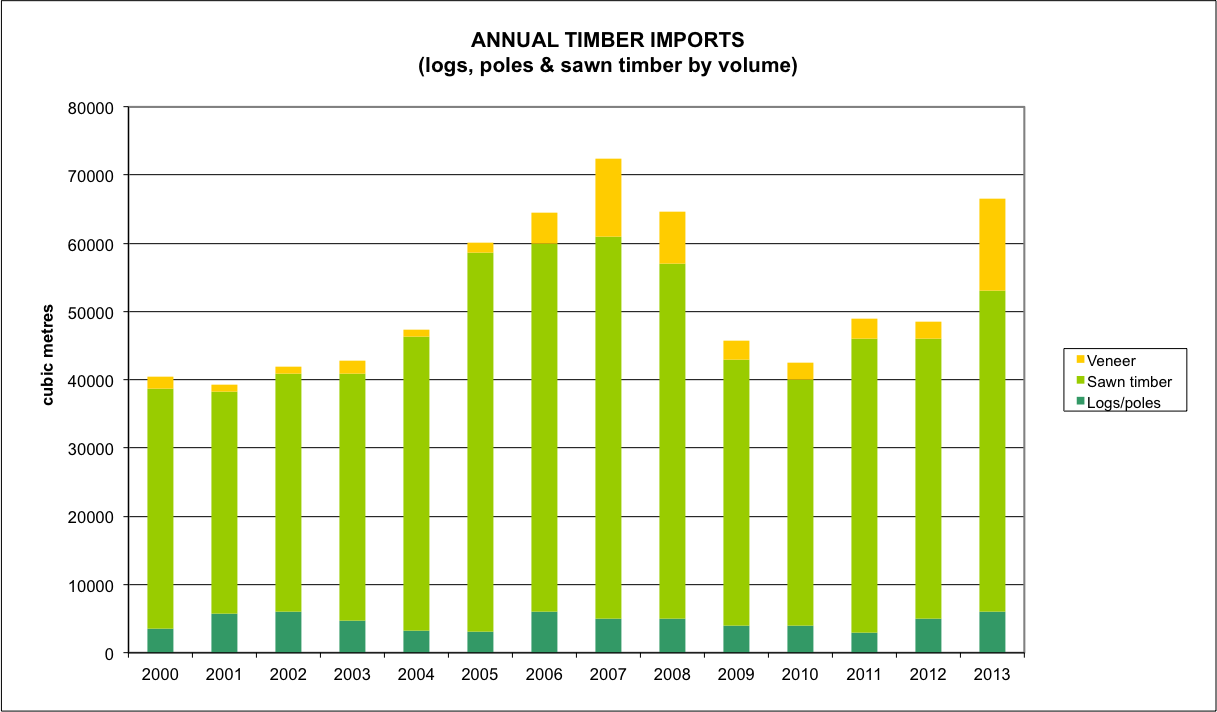

The graph above shows the annual change in volume of logs, poles, sawn timber and veneer for year end June 2000 through to June 2013. There are a number of additional points arising from the data:

- The total volume of all sawn timber imports including sleepers for the year to June 2013 is 47,366 m3 (up from 37,267 m3 for the year to June 2003).

- The total value of all sawn timber imports including sleepers for the year to June 2013 is NZ$57,429,000 (up from NZ$46,808,000 for the year to June 2003).

- Canadian Western Red cedar makes up 37% of all sawn timber imports.

- The main sources of imported sawn hardwood timbers are Australia, Fiji, Indonesia, and United States.

- Sawn timber imports decreased following the global financial crisis in 2008 but are now on the rise again.

IMPORTED TIMBER PRODUCTS – All Categories

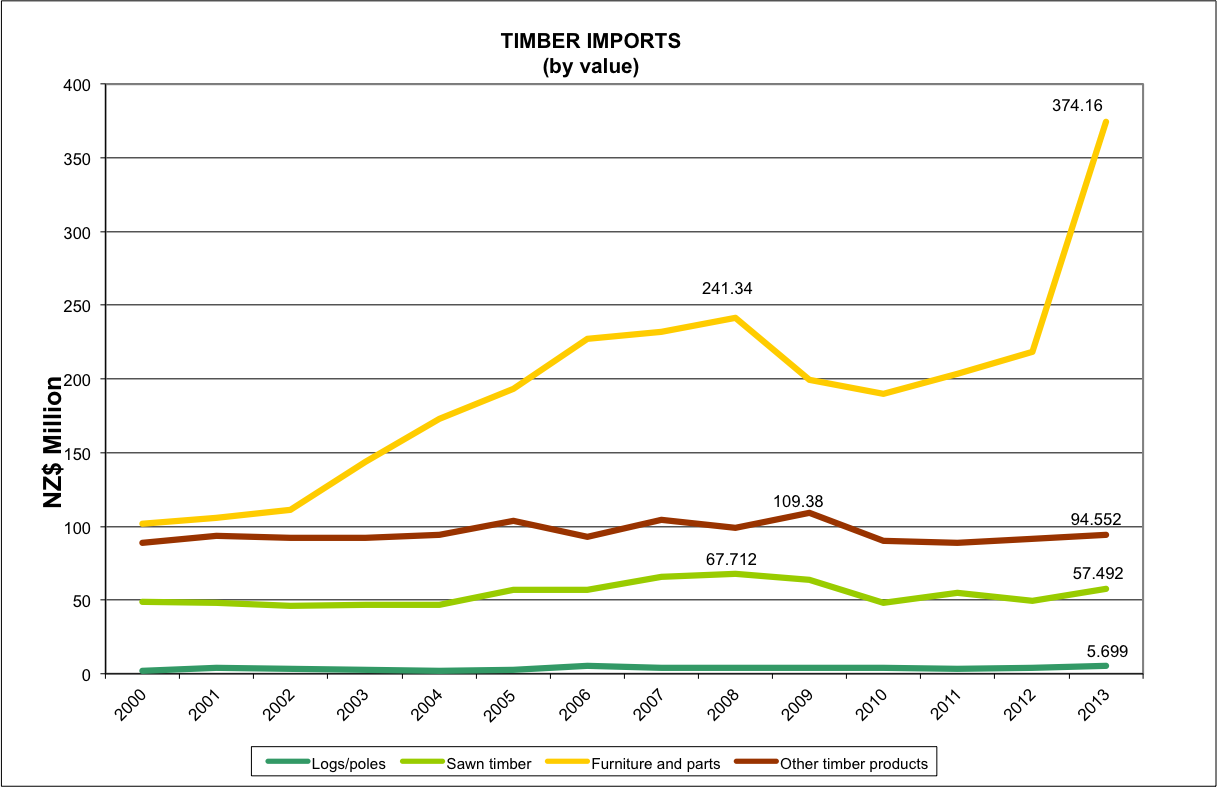

Logs, poles, sawn timber sleepers and veneer only make up part of all timber product imports. As can be seen from the graph below, furniture, furniture components and other miscellaneous wood imports make up the largest proportion of the annual timber imports.

There are a number of additional points arising from the data:

- The total value of solid timber imports has grown from NZ$88,720,000 in 1993 to NZ$284,000,000 in 2003 and now to NZ$531,900,000.

- The rate at which the value of solid timber imports is increasing exceeds 9% per annum.

- The value of imported furniture and furniture components is now more than twice all other categories of solid timber imports combined.

While some of these furniture imports may be radiata pine exported back to New Zealand, such reimportation is not recorded separately by MPI.

CONCLUSIONS

In simple terms, indigenous and special-purpose timber production in New Zealand continues to decline while imports of special-purpose timber products continue to escalate.

Many kiwis are happy to use imported timber products or specify imported timber for their floors, walls, ceilings, joinery or cladding without a thought as to the quality of forest management back at the source or the benefits of using NZ-grown wood.

In effect, New Zealanders have effectively exported the environmental impacts of their special-purpose timber consumption to other countries and failed to recognise the impacts of their actions on the sustainability of their own forests or the viability of their own special-purpose and indigenous timber manufacturing industries.

There is an obvious need to increase the public’s awareness of how their timber consumption patterns are at odds with the clean green conservation image we all cherish. New Zealander’s are unwitting partners in a double standard that requires high standards for their home-grown timbers but expect little in the way of sustainable credentials for special-purpose timber imported from overseas.

The market must operate within an equitable legislative framework if it is to reflect the environmental aspirations of the public. There is a need for legislation to be developed which controls the importation of unsustainably (not just illegally) produced timber. This lack of legislation distorts the market making it difficult for NZ producers to compete. Such legislation cannot be developed in isolation of our trading partners but World Trade Organisation restrictions can no longer be cited as reasons for not acting on this.

New Zealand’s environmental organisations also need to increase their support for home-grown special-purpose timbers and shine the spotlight on imports arriving without any sustainability credentials.

There is also a need for greater support from government departments for the use of our sustainably managed indigenous and special-purpose timbers. Currently, the government does not have a comprehensive forest policy and the level of government support for indigenous and special-purpose forestry is mediocre at best. Regional and District Councils also have a role to play. All these government agencies could support these industries by buying NZ-grown timber, especially naturally ground durable timbers.

We do not need a Resource Development Act

Chris Perley's BlogFriday, March 20, 2015

New Zealand has a comprehensive piece of legislation (Resource Management Act 1991) by which the use and development of ‘resources’ is managed. The current government is attempting to reform this legislation to make it more amenable for development interests. Corporate lobby groups are active with the government in pushing a case for reform. They essentially desire a Resource Development Act focused on money and the short-term, rather than a Resource Management Act focused on broader values and the long-term.

This article was written in response to an opinion piece by the CEO of the lobby group BusinessNZ.

I blame philosophy. I see phrases like “moving forward” and words like “prosperity” and “resources” and “development”, and have to ask, what does it all mean?

The CEO of BusinessNZ Phil O’Reilly (Dom Post 13th Jan) calls for what would be essentially a Resource Development Act to replace the Resource Management Act (RMA). He exposes his mechanical worldview – we are, along with the rocks, mere grist for the mill – and it is a wrong and dangerous one.

But ‘prosperity’ is not a matter of merely ‘developing resources’ to bring them to the factory and the market through the command and control actions of technically-trained human robots. Nor does his implicit faith in commerce and markets to think, decide, allocate and distribute the promised manna bear any relation to the real world in which we live.

The commoditising of life and land is the very opposite of where we ought to be heading if we want high wellbeing for all. The inevitable consequence of the industrial commoditisation agenda is the encouragement of power, privilege and short-term exploitation, as well as the discouragement of meaning, morality and wisdom.

The worldwide failures of this type of big-scale commodity thinking has led to calls for a more people- and place-centred version of ‘development’. There are too many names to quote[1], but they point the way out of our slide back into at best the dark satanic mills of the 19th Century, and at worst another social and environmental collapse brought about by our apparently unlimited ability to push our systems beyond the brink. We’ve collapsed many times before, but without the means until now to really destroy humanity. Understanding collapse ought to be a prerequisite for economists and those that play with money. A requirement to read a few great books might also help them develop a broader and longer perspective.

The likely-temporary prosperity that would result from Mr O’Reilly’s type of development would be a corporate dystopia suiting the narrow interests of a few who live with little concern for the future of either humanity or the planet within which we live and breath. Worse, their inability to see especially the long connections that bite back, coupled with short-term personal obsessions, will inevitably push our biophysical and social systems to the tipping point of failure.

Which is why we need the RMA. It remains one of the only community counters we have to the excesses of short-term avarice by politically and commercially powerful interests. It is also admirable in its structure and intent. Yes, have enterprise, harvest, invest, but there are bottom lines we will ensure in the interests of our future society and the values within our landscapes. Any concerns there may be are more to do with local governance and application than the Act itself. The case for reform is singularly avaricious.

There are those who believe that we don’t need the RMA because ‘the market will provide.’ With long-term natural systems and functioning societies it most certainly does not. If more money now is the measure, and future generations discounted by an exponential, then a financial case can be made to mine non-renewable resources as fast and as cheaply as possible – never mind people or place, or their descendants. It also makes perfect financial sense to simplify and destroy complex forests, fisheries and soils that take many decades to cycle and renew, and at best turn them into large-scale factories of high-input hydroponics and control – short-rotation plantations, fish farms, irrigated factory farms. Which is why financiers ought to be avoided when considering long-term issues like the proverbial plague.

W.H. Auden has a far greater understanding of exploitation than the failed – but still strangely living[2] – dogma of free market neo-liberal economics.

A well-kempt forest begs Our Lady’s grace;

Someone is not disgusted, or at least

Is laying bets upon the human race

Retaining enough decency to last;

The trees encountered on a country stroll

Reveal a lot about a country’s soul.

A small grove massacred to the last ash,

An oak with heart-rot, give away the show:

This great society is going to smash;

They cannot fool us with how fast they go,

How much they cost each other and the gods.

A culture is no better than its woods.[3]

As with finite and slow-revolving natural systems, so it is for communities. Disproportionately powerful interests will tend to exploit for a short-term increase in profit margins, which is partly why Adam Smith disliked the exclusive trade-rights of aristocrats, and those 18th Century corporations that pale before the transnational corporations of today in terms of their political and commercial influence. Conveniently forgotten, that part of Adam Smith’s writings.

The consequences of social exploitation are similar to the exploitation of natural systems. A feedback will happen, but it will likely come after the perpetrators are dead – their children’s children may be the ones to face the angry mob – or on other parts of society, or on a society elsewhere. The higher you discount the future, the more ‘rational’ exploitation becomes.

The primary purpose of the RMA is in a sense to bequeath our children legacies rather than an exploited wasteland. It is a vital piece of legislation, more so now when the rise of largely amoral commercial interests around the world seem intent on leveraging for yet more power and the right to exploit and degrade for the benefit of a few.

Chris Perley (Originally posted January 27 2015 on Chris Perley's blog >>)

Chris Perley has a background in primary sector and regional strategy, policy, research, and operational management across forestry, agriculture, community, economy and the environment.

[1] Herman Daly, Leopold Kohr, Jane Jacobs, J.K. Gibson-Graham, C.S. Holling, Manfred Max-Neef, Robert Putnam, E.F. Schumacher, Amartya Sen, Vandana Shiva to name a few.

[2] The strange non-death of neoliberal economics has shades of the non-death of communism before the ‘exclamation point’ of the Berlin Wall. Perhaps the next, bigger, deadlier global financial collapse?

[3] W.H. Auden Bucolics, II: Woods

Disclaimer: Personal views expressed in this blog are those of the writers and do not necessarily represent those of the NZ Farm Forestry Association.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand