PESTS AND DISEASES OF FORESTRY IN NEW ZEALAND

New Zealand drywood termite

Scion is the leading provider of forest-related knowledge in New Zealand

Formerly known as the Forest Research Institute, Scion has been a leader in research relating to forest health for over 50 years. The Rotorua-based Crown Research Institute continues to provide science that will protect all forests from damage caused by insect pests, pathogens and weeds. The information presented below arises from these research activities.

Forest and Timber Insects in New Zealand No. 59: New Zealand drywood termite.

(See below for introduced drywood termites)

Based on R.H. Milligan (1984)

Insect: Kalotermes brouni Froggatt (Isoptera: Kalotermitidae)

Fig. 1 - Soldier of Kalotermes brouni.

Type of injury

Nests of the New Zealand drywood termite are found in dead, sound wood. Dead, standing or fallen trees, logs lying in exposed situations, fence posts, power and telephone poles, and construction timber that has not been treated with preservatives can be suitable for nest establishment. The dead wood (heartwood) at the centre of living trees may also be invaded if the termites can gain access.

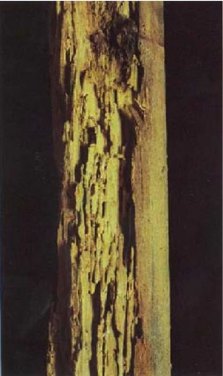

Where nests are well established the earlywood bands of the timber will be destroyed, leaving a series of longitudinal galleries separated by residual bands of latewood (Fig. 2). Smaller interconnecting passageways, which are roughly circular or broadly oval in cross section, may also be present, and may link subcolonies to the main nest. Even though no particular pattern typifies the workings, they can be immediately identified as those of a drywood termite by the shape of the faecal pellets found in disused parts of the galleries (Fig. 3). Except for the occasional small holes through which the winged adults emerge, the exterior surfaces of the timber remain intact.

Hosts

This termite will utilise dead, dry wood of a wide range of indigenous and exotic hardwoods and softwoods, and no timber species grown in New Zealand is known to be specifically resistant to damage. In living trees it has been recorded from the heartwood of Pinus radiata (radiata pine), Cupressus macrocarpa (macrocarpa), Eucalyptus (eucalypts), Metrosideros excelsa (pohutukawa), and Sophora (kowhai).

Fig. 2 - Workings of K. brouni.

Fig. 3 - Faecal pellets of drywood termites are elongate, rounded at each end, and hexagonal in cross section over most of their length.

Distribution

This native insect occurs throughout New Zealand.

Economic importance

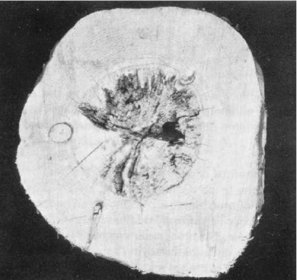

Drywood termite damage to heartwood may be so extensive within a living tree as to render logs useless for sawing (Fig. 4). In the past, heartwood damage was thought to be confined to trees that were open grown, or grown as shelter belts, but in recent years this type of damage has been found in pine trees in forests north of Auckland and in the Coromandel Peninsula. Although the incidence is not high it is of concern to forest and mill managers.

Fig. 4 - Heartwood of living radiata pine destroyed by K. brouni.

The presence of the insects in branch stubs is of no importance when trees are taken for use in New Zealand, or are milled before export, because the infestations are removed with the waste slabs during sawing. However, such logs will be rejected for export unless they are first fumigated with methyl bromide.

In buildings, conditions favouring development of drywood termites also suit the larvae of two-toothed longhorn (Leaflet No. 26) and house borer beetles (Leaflet No. 32), so it is rare for drywood termites to be the sole deteriorating agent. However, as building timber does not usually exceed 75 cm2 in cross section, the presence of even small nests can cause areas of structural weakness. In addition, because exit holes are inconspicuous and few in number, the damage may remain undetected and become widespread in the building before the need for remedial action is realised. Houses closely surrounded by neglected shelter trees may be more susceptible to damage than others.

Description

Different sorts of individuals (castes) arise from the eggs of drywood termites. The relative numbers of each caste are regulated by the needs of the particular community and controlled by hormones passed around during feeding.

By far the most numerous occupants of a nest are the young or "nymphs" (Fig. 5). They are white to pale yellow, except for the jaws which are dark brown to black. External wing buds are present which become larger each time the nymph sheds its skin. The nymph moults several times before reaching a final length of about 5 mm. The more mature nymphs undertake the function of workers - extending the galleries, removing debris, and tending the queen and other dependent members of the colony. A sterile worker caste, such as occurs in some other groups of termites, is not found in the family Kalotermitidae.

Most nymphs ultimately develop into winged male or female reproductives (Fig. 6) which emerge, disperse during mass flights, and pair. However, only a few pairs succeed in establishing new colonies elsewhere. A winged reproductive has two sets of greyish wings which, at rest, lie flat over the abdomen and project about 5 mm beyond its apex. Its body is about 5 mm long and yellowish brown. Its head is shaped like a sphere flattened above and below and bears moderately long, thread-like antennae. The segment behind the head is saddle-shaped, and wider than the head. The front part of the abdomen is narrower than the head, and widens out towards the rear. Near the base of each wing is a line of weakness. Before a pair of reproductives begin to tunnel into fresh host material, the wings are deliberately broken off at these places. The wing stubs that remain distinguish the founders of the colony from their winged offspring. The female founder can also be distinguished by her greatly enlarged abdomen.

Fig.5 - Nymphs of K. brouni.

Fig. 6 - Winged reproductives of K. brouni. (Heads and antennae became folded underneath when these specimens died.)

If a parent pair, or just the mated female, or queen, should die, or if part of the colony becomes separated from the queen, nymphal males and females can become sexually mature even though their body forms remain immature and functional wings are not developed. These "emergency" reproductives resemble larger nymphs, except that the abdomen of the female may be enlarged. They serve to maintain the population of the nest in the face of natural mortality.

Some sterile individuals of both sexes develop unusually large and abnormally shaped heads which are dark red in front and paler behind, almost twice as long as they are broad, parallel-sided, and rounded at the rear. They have robust black jaws which are about a third as long as the head (Fig. 1). This is the soldier caste which protects the colony against insect invaders, particularly ants. The jaws of the soldiers are especially shaped for seizing invaders, and are quite unsuitable for gouging out wood particles, so soldiers must be fed by other members of the colony.

Life history and habits

The lifespan of a mature New Zealand drywood termite, the time taken for individuals to develop from egg to adult, and the length of each of the developmental stages are all unknown. The development of a colony is usually a slow process, but once established its life is limited only by the availability of sound, dry wood.

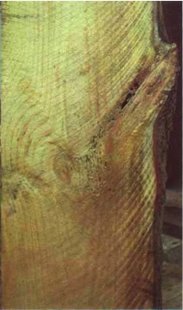

After swarming flights in the late summer or autumn, each pair of winged reproductives selects a site for the establishment of a new colony. Preferred sites are the flight holes and pupal chambers abandoned by longhorn beetles, but other concealed situations may serve. Where living pine trees are chosen, pairs start from dry suppressed or broken branches which have previously been invaded by longhorn beetles such as Calliprason pallidus (Leaflet No. 6). In macrocarpa, exit holes of the longhorn beetle, Eburilla sericea, in recently killed branches, or those of the two-toothed longhorn beetle, Ambeodontus tristis (Leaflet No. 26), in older dead wood are common entry points. The drywood termites may then advance into the heartwood through the traces of the dead branches (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7 - Damage to heartwood of living radiata pine after K. brouni entry via branch stub.

Success of drywood termites in living trees appears to depend on dead branch stubs remaining so dry that they are not rapidly broken down by rot fungi and insects. If suppressed lower branches rapidly decay back to the living stem then the branch traces become overgrown by new wood and no longer provide a pathway which drywood termites can follow to the heartwood. In conifers, resin reactions of living sapwood to wounding can also effectively deter would-be insect invaders.

Control

Heartwood damage is least likely if broken and suppressed branches are pruned back to the living stem, and dead dry wood on the ground which could harbour colonies is destroyed.

Damage to new buildings is best prevented by the consistent use of preservative-treated timbers. Drywood termite damage in old buildings is unlikely to be detected until timbers are seriously weakened, so a full survey of the extent of the damage should be made before attempting to eradicate the insects. If timbers are only slightly damaged remedial treatments such as fumigation or injection of insecticides may be appropriate, but weakened timbers should be replaced.

Bibliography

Bain, J. and Jenkin, M.J. 1983: Kalotermes banksiae, Glyptotermes brevicornis and other termites (Isoptera) in New Zealand. New Zealand Entomologist 7: 365-371.

Emberson, R.M. 1984: Forest and timber insects in: Scott, R.R. (ed) New Zealand pest and beneficial insects. Lincoln University College of Agriculture, Canterbury, pp 191-204.

Kelsey, J.M. 1944: The identification of termites in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Science and Technology 25(6): 231-260.

Kelsey, J. M. 1946: Insects attacking milled timber, poles and posts in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Science and Technology 28(2): 65-100.

Milligan, R.H. 1984: Kalotermes brouni Froggatt, (Isoptera: Kalotermitidae). New Zealand drywood termite. New Zealand Forest Service, Forest and Timber Insects in New Zealand No. 59.

Waller, J.B. 1984: Household pests in: Scott, R.R. (ed) New Zealand pest and beneficial insects. Lincoln University College of Agriculture, Canterbury, pp 205-220.

Zondag, R. 1959: Attack by Calotermes brouni Frogg. on living Pinus radiata . New Zealand Entomologist 2: 15-17.

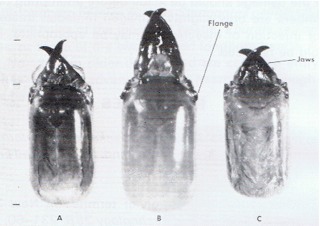

Introduced drywood termites

Two Australian drywood termites (Kalotermitidae) are present in New Zealand. Neither has yet been found in forests, and neither is expected to be of any economic importance. Generally the easiest way to identify the species is by the shape of the head and jaws of the soldiers (Fig. 8).

(1) Glyptotermes brevicornis Froggatt. First discovered in March 1977 in Auckland, and subsequently found in Whangarei (1980) and Hawke’s Bay (1991). New Zealand hosts have been logs or dead parts of live trees of Pinus, Cupressus, Populus, Fraxinus, Sequoia and Salix. Only once in New Zealand has it been found damaging a building. In 1988 it was found infesting a Dacrydium cupressinum (rimu) architrave, window sill and a skirting board. In Australia it inhabits a variety of hardwood and softwood stumps and logs.

(2) Kalotermes banksiae Hill. This termite has been present in New Zealand since at least 1939. It is established in the North Island on the east coast of the Coromandel Peninsula, and along the coastline from Castlecliff Beach near Wanganui to as far south as Waitarere and Matakana Island (Bay of Plenty). In the South Island it is found from Farewell Spit to the Boulder Bank in Nelson, on the Marlborough Coast at Kekerengu, at Cape Foulwind near Westport and Greymouth. New Zealand hosts have been driftwood, branches, fairly sound logs, or tree stumps of radiata and other pines, Salix (willow), Nothofagus fusca (red beech) and N. menziesii (silver beech) either on or very close to sandy beaches. In Australia it is known from logs and dead snags of Banksia integrifolia (coast honeysuckle tree), Myoporum (ngaio), Eucalyptus , and Casuarina (sheoak). There is one Australian report of it in pine door frames and Eucalyptus marginata (jarrah) door sills. As in New Zealand all sites were on sand near the coast. An observation that may aid in field identification of this termite is that the soldiers seem more numerous and more active than those of K. brouni.

Fig. 8 - A comparison of the head and jaws of the soldiers of the drywood termite species present in New Zealand.

A Kalotermes brouni - New Zealand drywood termite.

B Kalotermes banksiae - introduced Australian species.

C Glyptotermes brevicornis - introduced Australian species.

Note:

- The relative lengths of the jaws. Kalotermes banksiae the longest; G. brevicornis the shortest.

- The relative size of the heads. (However, within a single colony there is often quite a range of sizes, and so there is some overlap between the species. It is the relative proportions that are important.)

- The prominent flange on K. banksiae which is a useful identification character.

This information is intended for general interest only. It is not intended to be a substitute for specific specialist advice on any matter and should not be relied on for that purpose. Scion will not be liable for any direct, indirect, incidental, special, consequential or exemplary damages, loss of profits, or any other intangible losses that result from using the information provided on this site.

(Scion is the trading name of the New Zealand Forest Research Institute Limited.)

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand