Whangarei Conference 2015 - field days

Whangarei branch committee, New Zealand Tree Grower August 2015.

The annual NZFFA conference was held in Whangarei in April and as usual there were a number of field trips for attendees to take part in. Over the next few pages are reports of some of these visits. The weather was kind which was a relief to the organisers.

The previous Whangarei conference, about 25 years ago, was ‘cold and miserable’ according to some of the participants who still remembered it well. The winterless north all those years ago did not live up to its reputation, but this year the sun shone and the temperature stayed high.

Whangarei Heads

On the Tuesday morning we were taken to Reotahi on the edge of Whangarei Harbour. First there was a walk along the edge of a marine reserve and past some impressive pohutukawa trees before stopping for the first presentation. This was from Greg MacNeill who works for Refining NZ.

We looked out over the harbour at the refinery and a large crude ship which had arrived from Middle East with its oil cargo. The oil is owned by four oil companies not the port, and money earned by processing the crude is the refiners’ margin. Last year the revenue was $233 million with a profit of $10 million although in the early part of the year they were losing money due to falling world oil prices.

A total of 500 staff work at the refinery making it one of Northlands biggest employers. The refinery processes 40 million barrels of oil a year and produces about 70 per cent of the petrol and diesel which New Zealand uses. The company Z Energy have contracts with large refineries and buy at a discounted rate which puts pressure on the refinery to keep the prices competitive. Current low crude prices means that it is cheaper to process, but as processed oil prices have not fallen they admit they are making more money. Recently building means they can refine two million barrels a year more.

Northport

We then heard more about Northport which we could also see across the harbour, along with ships about to be loaded with logs and a large pile of woodchips which were ready to be exported. Ben Sweeney, an engineer at Northport, explained that 20 staff and up to 300 contractors were on site at any one time. The port is half owned by Tauranga and half by a subsidiary of the regional council. The port was constructed in 2002 so is the newest one in New Zealand. As a result all water is treated before going into harbour compared with others where it is washed directly into the sea.

The port exports 3.2 million tonnes of wood a year, of which 2.5 million tonnes are logs, the rest as wood chip. Of these exports, 80 per cent go to China and the remainder to India.

They want timber to be moved in and out quickly because the port is paid on tonnes loaded or taken off a ship. Therefore speed is important. The ships bring in coal for Golden Bay Cement, fertiliser and palm kernel extract for dairy farms.

When prices are low some log suppliers want to hold on to them until the price rises so they have to keep that under control or the port fills up. Customers get eight weeks of free storage on the port but any additional time has to be paid for. This means that bigger suppliers have better systems and are more efficient as they are likely to be able to fill a ship quickly. Ships take around two or three days to load but may have stopped at other ports beforehand.

Wood chips are loaded on to ships using a conveyor and each ship, about one a month, carries about 35,000 tonnes which takes 72 hours to load. The wood chips are trucked in from Portland. The pile of chips we could see, about two shiploads, was virtually all radiata pine with a small amount of acacia.

Fonterra send nothing out via the port as no container cranes are available and all dairy products go on rail to Auckland or Tauranga. Northport port would like cranes and installing them is in their plans. They currently have room for expansion for the 570 metres of berth space and have resource consent for another 270 metres as well as for four hectares of storage land. Rail connection would help especially for timber but would make the timber more expensive due to extra handling.

Kaeo for totara, radiata, kauri and cypress

When we arrived at Paitu, Doug Lane explained that he would be taking us around the property although he sold the farm seven years ago. Planting was started by his father and in 1990 they harvested some of these pines and this sparked his interest in trees. At the time he was making 20 dollars a hectare from his hill country and it seemed a good idea to spend money on the better land.

As a result for the next three years Doug planted 10 hectares a year in radiata, then gradually changed to lusitanica and other cypress deciding that fewer trees of higher value was a better option. The aim was to plant any land on which they could not safely take a fertiliser spreader and to make a more pleasant environment.

After the first three years Doug realised there was not sufficient income available to prune and run the farm as well. So he got a joint venture partner for pruning and thinning. The partner was to get a third of value at harvest.

Totara a native resource

We then walked to the block of totara which, we were told, was just about head height 50 years ago. As the photographs show, we were now able to see some sizable trees.

Paul Quinlan from the Northland Totara Working Group explained how they were trying to change totara from being seen as a weed to being an asset. Totara is very stock resistant so there is no planting or fencing costs. It is abundant, regenerates naturally and responds well to pruning. The old growth timber is very good but the new timber is a bit different.

The working group are trying to quantify growth response, determine wood quality of the new growth then develop a supply chain and at the same time to look for any problems. The aim is for a regional resource from all the small blocks available in the region which amounts to around 44,000 hectares in total.

Totara is not being used in any commercial scale. Its use is all informal due to lack of continuity of supply. It has potential and is a good timber with research being carried out to develop a code of compliance for use in buildings.

Local supply

In this catchment of just a couple of farms, around 1,000 cubic metres of totara a year are available on a sustainable system. Just a few more farms added would make a real difference but we were told that it can be done. It could be a multi-million dollar industry in Northland for a sustainably managed natural resource and could be a trailblazer for all sustainable species.

The productivity varies a lot from site to site. However diameter increase are from around three millimetres to seven millimetres a year with the best trees adding as much as 10 millimetres a year.

As part of the question session John Wardle said that the new growth does not have the same durability as old growth and it is a brittle timber not suitable for building. Paul said that the timber is currently being tested and did not agree that it was brittle. In his opinion it is equivalent to macrocarpa, with a market as interior lining and veneer.

Radiata harvesting at Paitu

The next part of the field day involved a radiata pine plantation. This was planted in 1991 at 1,000 stems a hectare and thinned to 400. The discussion was started by Gary Leslie of Northern Forest Products a company which buys wood from forest blocks as standing trees for subsequent harvesting.

He admitted that the business of managing forestry harvesting is cut-throat. Because for many of us harvesting a block of pine may only happen once in a lifetime, it is difficult to know when you are getting a good deal. He said to make sure that, as a forest owner, we get all the proper paperwork including a copy of the invoice which went to the mill and exactly what went into the bank account.

Gary has, in his words, put his money where his mouth is and says he is one you can trust. His company Northern Forest Products assess the forest and then offer what they think is a fair and competitive price for the standing trees, a price which can be negotiated. He pays for the wood in advance and this avoids suspicion when harvesting and is security for the forest owner. The only uncertainty for the owner is how the site is left after harvesting and he makes sure that is not a problem.

Location, location, location

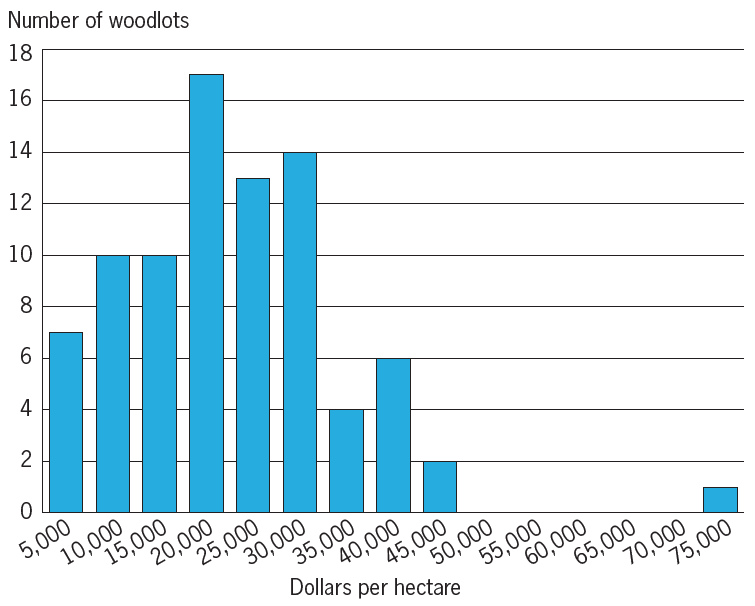

The next speaker was Graham West of Scion, mainly concerned with a promotion of MyLand which is for mapping and keeping records. The system has been sponsored by the NZFFA and is available free of charge. However, there was more interest in the other page of the handout with a graph showing the results of a survey on what a range of people got from selling their woodlots.

There was information on 84 woodlots sales in the North Island which had an average area of 14 hectares and an average net return of just over $20,000 a hectare. However, as the graph shows, some people got as little as $5,000 a hectare but at the other extreme one woodlot achieved $75,000 a hectare. As Graham said, this is because forestry is very like real estate where it is all about location, location and location.

Why did one woodlot get such a high return from its 12.9 hectares of just under a million dollars? The land was very productive, giving 800 tonnes a hectare at a tree age of 28 years. Most importantly the woodlot was near the road, on flattish land and close to a port.

Then we got back to discussing how to make better decisions and to have a good experience using MyLand. This computer software is freely available but not many people are using it. Graham said that it could well be too complicated for many people, but for those who did it was a good way to measure and keep records of your woodlot.

Kauri as a timber crop and cypress pruning

We next went to see how some young kauri were growing. These were planted in 2006 and have grown very well although almost as good as pine. We heard how plantation grown kauri on private land can become substantial trees quite quickly. Some trees 17 years old on a site north of Tauranga have a stem diameter of 34 centimetres and putting on diameter of two centimetres a year while growing between one and two metres a year in height.

Many people do not expect much from kauri and having planted them are very surprised they are not dead within a year or two. Wood density studies of the rapidly rapid growing trees shows that the density is same as in 200-year-old trees which have grown at a much slower rate. The sapwood has same strength properties as old growth heartwood but does not have the same durability.

A few cypress

The final stop was next to a block of cypress which Doug calculated had been planted in 1996 at 1,000 stems a hectare then pruned to two metres at about year three or four. The aim of the pruning was to reduce windthrow and the block had not been thinned.

We heard from Dean Satchell about cypress. His first concern was to ask about the seed line for the trees but the answer was not available or as is termed ‘nurseryman’s special’. There is very little canker on any of the cypress on the whole farm, with some on only one of the tree stems we were looking at. This was said to not be a problem as the damaged trees can be easily thinned out. The aim should be to plant enough trees so the poor or diseased ones can be removed later. Apparently if the other trees do not have canker by now they will not get it.

Pruning thoughts and discussion

There were many different options to consider with regard to pruning as is always the case at field days where cypress are being discussed. One problem is that 95 per cent of macrocarpa planted in the past 25 years are from the same canker-susceptible seed line – longwood – and this has ruined the reputation of macrocarpa. Apparently new seed lines will give good results.

If you are going to prune them, and you do not need to, follow through to and thin them also. Otherwise there is no point in pruning as the saw logs will not get big enough to produce clearwood. With radiata pine the aim is to have more sapwood but with cypress you need more clear heartwood – this is the bit of wood between the sapwood and the knotty core, so you need big logs.

On this site some growers would be thinking of lower prune heights to get fat butt logs. In this case the stocking could be down to as low as 200 per hectare but it was questioned if it was economic to grow at this density, both in terms of recoverable volumes but also risk of toppling. However, the butt log is only about half the available wood and is easy to sell. The ‘knotty’ part of the macrocarpa is a nice wood but it needs marketing for those who like wood with knots.

If you thin too rapidly there will be larger branches higher up so pruning is a bit of an art form and thinning needs to be slow and careful. Every cypress grower will give a different opinion and Denis Hocking suggested that even as low as 100 stems per hectare can work on longer rotations.

Adding value with trees

The presentation was concluded by a discussion about the value of leaving trees standing. Doug sold a block of 50 hectares which had a QE II covenant on part of it. The buyer said this was why he bought it – because it added to the value. The value is not just sale of timber, but what you get from seeing the landscape. Rural valuers will often say that trees on your farm add value. However you may only get that value in dollar terms when you sell the farm.

Parakao and the Pedersen property

The next full day of field trips started with half of the attendees visiting Parakao. John Pedersen moved to Parakao 50 years ago as a child when his father bought 240 hectares of mixed scrub and pasture. There was significant native bush in the gullies but no exotic trees of any kind. On a misty morning, John and Christine welcomed us for the last full field day of the conference.

John explained that a few years ago meat prices were so low that the only way to be one-up on the buyers was to supply less. So he decided to reduce the number of sheep and plant blocks of trees. As they planted more he said tree planting became addictive and even more trees were planted in paddock corners with Peter Davies-Colley giving advice about having trees as a resource.

John also said that it was good to start early in life with forestry and important to get children involved. Mathew, his son, explained how he was given a bit of land to plant with some trees and that always got him involved and was always keen to come back home and do some silviculture. Mathew went on get a diploma in forestry management and now works for PF Olsen.

The forestry is now at what John thinks is the fun part as it will soon to be time to cut the trees down. However, John and Christine prefer to look at the trees than see them all harvested and get the money, which is no bad thing. This comment adds to what we heard the previous day about trees on farms adding value just by being there, and again at the conference in 2014 where a recent farm valuation included up to 25 per cent for the amenity trees.

Forest research and protection

At this first stop we heard more from Scion, to add to their already significant contribution to the conference field days. This time it was about forest protection research covering insect pests, pathogens and weed control. Scion has produced a useful booklet which covers assessment, identification and control of foliage diseases of radiata pine. We were all given a copy and it is almost a dummy’s guide, in that the colour pictures and descriptions of the various common diseases of pine needles make it very easy to follow. If you want a free copy, contact Scion.

Four main common pine diseases were outlined. Dothistroma seems not to be a problem in Northland. Phytophthora diseases include red needle cast and physiological needle blight, the latter being common in Northland. Finally cyclaneusma was discussed but is mainly controlled with good genetics.

Role of soil fungi

After a pleasantly exhilarating walk up a steep hill, we reached a good vantage point where we could see most of the farm and the trees John had planted. Before we heard about some of the forestry developments visible in the distance, there was a presentation about soil fungi and encouraging good mycorrhizae. Too much fungal treatment in many nurseries removes good mycorrhizae which are necessary for better tree growth. Tree nursery costs can be reduced and there will be better results if less fertiliser and fungicide is used. If the seedling is then looked after, the mycorrhizae will stay in the roots when planting and gradually allowing those on site to eventually take over.

Some tree clones are better than others at encouraging mycorrhizae to grow with the tree. It works for no cost, although adding boron is one way of encouraging mycorrhizal development. Research on five sites around the country is being carried out to test how boron helps mycorrhizae as there is a lot not yet known about the effect of boron. Soil science has been a poor cousin and a lot more research needs to be carried out.

Scion is running some workshops to show how to sample soil and improve what you do. It is expected there will be a workshop in the North Island sometime in July or August.

Harvesting

We could see in the distance some of the harvesting which Hancock Forestry are carrying out using mechanised tethered felling and a camera operated grapple. The land we were looking at had slopes up to 45 degrees and was not a suitable site for workers with chainsaws.

We heard how the work had become more efficient as the men got used to the new machinery. The crew of nine men at first averaged 250 tonnes a day but are now averaging 350 tonnes. The overall cost is $10,000 a day, which means that for 350 tonnes the cost is about $30 a tonne. However, when transport of the gear on and off site is included this could increase to give average of around $40 a tonne.

We then got to discussing harvesting on the farm where the trees are in small woodlots and gullies.

The first part of the harvesting plan will involve 10 blocks producing around 1,500 tonnes of logs for which harvesting costs could be quite high. Traditional harvesting techniques will not necessarily work. Constructing new roads would be expensive and not a practicable option. Off-road trucking of the timber would probably be the only solution as they will not be able to get a logging truck to all the individual woodlots.

We were told that the biggest advantage you can give yourselves for efficient harvesting is time – plan well ahead and get as much information as you can about everything. Ask for advice, talk to contractors and understand what they or the harvest manager may be talking about. This will make it easier for you to understand the costs beforehand including indirect costs such as clean-up and road rehabilitation.

It was also important to develop a relationship with people you can trust, find out what others have done and what went right and what did not go right. The whole process should be fun and if you are only expecting to have one harvest in your lifetime there is no point in not liking the process. The concluding advice was to aim to enjoy your tree harvesting.

Eucalypt harvest and milling at Titoki

The second half of the last full conference field day was a visit to the Davies-Colley property where we were reminded that this had been the venue for a field trip at the 1991 conference. The farm had been bought in early 1960s by his parents Richard and Wilma Davies-Colley. It had been a dairy farm with virtually no grass and scattered totara with blackberry in between. As there were hardly any fences a lot of fencing and planting was needed to improve the productivity. The total area is around 300 hectares now, with 100 hectares of native forest remnants and plantations.

In the 1980s Peter and his wife Nikki bought the farm and developed a forest management business. As a result the farm needed a manager and it is now leased to a manager wintering 600 cattle. Peter lives on the farm where he runs his forest management business.

Is farm forestry still relevant?

Before Peter started his presentation he raised the question about whether farm forestry was still relevant. He believes that it is still very relevant and encourages innovation. On this farm conservation planting was required to reduce erosion and gullying. Frequently holes would open in the ground and these needed to be fenced off from stock although the fences often moved downhill after rain.

Richard decided to aim for multiple benefits from trees − erosion control, shelter and eventually logs and timber. They used a company which also exported logs to China and wanted more poplar. They therefore harvested 1,200 tonnes of these poplar logs. They then had to consider second rotation on the sites and could see the benefits of replanting poplar. The replanting process was a bit different from the first time when they were pushing three metre poles into the middle of blackberry.

Profitability of pruned poplar

Was it more profitable to export the pruned poplar? In theory no pruning was needed because it was the perfect agroforestry tree, combining agriculture and forestry. But to allow the grass to grow between the trees pruning was required. There is a market in China for poplar and it brings about the same price as radiata as they are quite used to working with poplar timber.

China uses poplar for veneer and can peel tissue thin veneer from the smallest branches. This is put on particle board for a high quality appearance, much better than New Zealand can manage.

Is it profitable to grow spaced poplar when it is compared with radiata? Yes, it was very profitable as the land has stopped moving, the lambs stopped falling in the holes, there was shelter and shade and poplar fodder kept cattle alive in the droughts. The nett return from the logs may be the same as radiata but there had been so much value from the trees as they grew, sale of the logs was pure profit.

You can grow good grass to the base of the tree with poplar but not with radiata as it does not let light to the pasture. This is farm forestry and solving environmental problems is not what radiata can do as well.

Special vehicle

We were given a demonstration of how Peter is now able to harvest logs from woodlots where there is no road access for a large trucks. Even small cable haulers are not cheap to set up and their availability is quite restricted. The alternative cost of new roading to and from small woodlots can increase the harvesting costs significantly and may even mean that the project is not worthwhile financially.

The truck, which Peter obtained second hand, has been modified to carry logs almost anywhere and the demonstration was impressive. There is still quite a lot of development work required and safety problems to solve. However, this kind of machine may make a significant difference to the viability of harvesting small woodlots in less accessible parts of a farm.

Pine productivity

Scion led a discussion about pine productivity and about what is going to happen after 2035 when there is less wood available due to the decline in tree planting. Investment in wood processing will not be popular without more trees being available. Harvesting could continue to increase for a while but eventually there will not be enough trees or enough harvesters.

First of all we were asked to understand a bit more about radiata productivity. The average pine productivity is about 24 cubic metres for each hectare of radiata pine forest every year. Some averages can be as high as 60 cubic metres a year in south Taranaki which has plenty of rain and suitable temperature. But if a forest owner could increase the productivity average from 24 to 29 cubic metres a year, just another five cubic metres on each hectare every year, over a period of 30 years this would be another 150 cubic metres of harvestable wood.

Wood quality

But what about the wood quality? Using trials from 1980s and 1990s looking at different spacing and effect on wood quality it seems that the wood volume is at its maximum at 400 stems a hectare. If trees are thinned to below 400 stems a hectare wood density falls. If you thin down too low you sacrifice the volume as well as wood quality and the stiffness of timber you will get at harvest.

Genetic gain has also been studied to see what you actually get from the higher GF radiata pine seedlings compared with the hopes and expectations of these at planting. It has now been shown that using improved GF gives a 25 per cent gain over the unimproved material.

There was a question about current annual increment and mean annual increment. If you wait until the trees are 30 years old when harvesting you get a lot more volume that harvesting trees at age 22. But when is the optimum age to harvest when current annual increment and mean annual increment are the same? For radiata pine this is around 28 to 30 years. If you fell after 30 years the trees will have more wood but at diminishing returns.

It was noted that for logs exported to China buyers want a minimum tree age. If they are sent younger logs, such as those from trees at just 20 years old as suggested earlier at a conference field day, it is not a good idea. China values quality and in the long term they will not be happy with low quality. Size does not matter as much as the quality of the wood.

Eucalypt milling

The final part of the day was a session on milling eucalypts and a continuation of the subject of innovation. Peter explained how he has learned to work with eucalypts since he bought an old Woodmizer and wanted to mill hardwoods. He has now developed a sawing pattern for eucalypt logs and for three months of the year he mills eucalypts and supplies a company in Whangarei which uses the wood for hardwood floors. Eucalypts have growth stress which is released when they are cut and he showed this with a section of log he had cut on the mill which had a distinctive upward curve on one side of the cut at the top. This can be a problem for most millers as this is the reference face and it is not square.

But once the stress has been released it is not there anymore and the reference face for cutting a straight board is the one left on the mill base. There is still the problem of the compression core in the centre of the log which will not dry well and an example is shown in one of the photographs. The aim is to box this out, or remove it completely. Peter showed, with his safe use of a whiteboard and pen, how to make the cuts outside the core by first marking on each of the log where the core is and then cutting it out. By cutting parallel to the first cut and turning the log over using the straight faces he does not have to keep making more reference cuts. This is followed by quarter sawing with the grain at right angles which is more stable for flooring. He made it all sound relatively simple.

Peter can cut about a cubic metre of eucalypt a day in this way with the help of a couple of assistants. It is challenging but good fun and earns about $1000 for each cubic metre. He says it confounds the critics who have said there are only two sorts of eucalypts − those easy to split for firewood and those which are not.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand