Eucalypt species selection and biological risk

Thursday, July 19, 2018, Dean Satchell's blog

It is well known amongst eucalypt growers that the wrong species choice will result in poor tree establishment, along with poor growth and poor form.

Soil fertility, soil moisture, wind exposure and frost each offer site challenges. However, it is also well known that species and genotypes can be selected for adaption to these variables.

There are also two biological risk factors that influence the success of the resulting crop. These are pests and pathogens. New Zealand has a long history of eucalypt plantations being exposed to high levels of damaging organisms, and that battlefield is ever changing. However, there are two key lessons that have emerged from the empirical evidence:

- Species susceptible to fungal pathogens require cooler, drier sites. Foliar diseases can be managed by siting appropriately.

- Insect pests are an increasing problem on the symphyomyrtus group of eucalypt species, with the list of species subject to heavy defoliation increasing steadily over time.

There is no doubt about it, biological risk is the key constraint that discourages investment in eucalypt plantations. The following summary discusses and rationalises issues that have the potential to both influence research investment decisions now, but also the future reputation of eucalypt forestry in New Zealand.

Growers observe what is happening around them and make decisions based on their individual perception of risk. The investment risk that industry as a whole faces is on delivering research outputs of value to growers. If decision makers ignore strong historical evidence suggesting that research efforts are likely to fail, if failure then occurs not only will the resulting loss of confidence in a species have been avoidable, but there will be no second chance given by the individual grower.

Biological risk factors are dynamic. Thus evaluating risk and making good decisions requires being well informed. Industry-good research must also aim for deployment at a scale that generates a valued resource and that results in a sustainable industry where investors have confidence and are comfortable with the level of biological risk they face. History suggests that this will not be achievable from species within the symphyomyrtus group of eucalypts.

Fungal pathogens

A suite of Australian fungal pathogens entered New Zealand during the 1980's. Until then siting of eucalypts was straight forward, much like Douglas fir, which could be grown anywhere in New Zealand before Swiss needle cast arrived. No longer could we plant Eucalyptus nitens and E. regnans in warm, humid sites. They became limited to cooler sites and are now known as "cool climate eucalypts". Such diseases have not actually removed these species as plantation options, they are now just limited to sites that are not warm, humid and wet. After a disease arrives we collectively learn about species limitations, but this has also corresponded to where the species is also limited in its natural environment.

Insect pests

More importantly, insect pests have frequently hitched a ride from Australia and continue to do so at a steady rate. Insect pests pose a serious problem because they can be very destructive and tend to specialise. In general, eucalypt pests each have their favourite species to attack and because they usually arrive without natural enemies, can reach plague proportions on that species.

Although the consensus from those less well informed might be that Eucalyptus carries an excessive biological risk for commercial plantation forestry in New Zealand, what is critically important to understand is that the Eucalyptus genus can be divided into two key groups, the pest-resistant group (monocalyptus) and the pest susceptible group (symphyomyrtus). This general rule helps with both species selection and in addressing risk. That is, if you are resigned to spraying your plantation with insecticides, then go ahead and plant symphyomyrtus species. If you are risk-averse then grow monocalypts.

Monocalypt species include the ash group (e.g. E. fastigata, E. obliqua, E. regnans) and stringybark group (e.g. E. muelleriana, E. globoidea, E. pilularis, E. sphaerocarpa)

Symphyomyrtus group eucalypts include the blue gums (e.g. E. globulus, E. nitens, E. saligna, E. botryoides), boxes (E. bosistoana, E. quadrangulata) and red gums (E. camaldulensis, E. teretecornis)

Lets have a look at the evidence*:

| Pest | Arrival date (approx) |

Level of damage Symphyomyrtus |

Level of damage Monocalyptus |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glycaspis brimblecombei | 2017 | Serious | Nil |

| Paropsisterna variicollis | 2016 | Very serious | Negligible |

| Paropsisterna beata | 2012 | Serious | Negligible |

| Thaumastocoris peregrinus | 2012 | Serious | Nil |

| Creiis lituratus | 2002 | Minor - moderate | Nil |

| Anoeconeoassa communis | 2002 | Minor - moderate | Nil |

| Nambouria xanthops | 2000 | Minor - moderate | Nil |

| Acrocercops laciniella | 1999 | Minor - serious | Minor |

| Uraba lugens | 1997 | Minor - serious | Minor - moderate |

| Cardiaspina fiscella | 1996 | Serious | Nil |

| Trachymela catenata | 1992 | Moderate | Negligible |

| Ophelimus spp. | 1990 | Moderate - serious | Nil |

| Ctenarytaina spatulata | 1990 | Minor - moderate | Nil |

| Phylacteophaga froggatti | 1989 | Moderate | Minor |

| Glycaspis granulata | 1986 | Moderate | Nil |

| Trachymela sloanei | 1975 | Moderate - serious | Negligible |

| Ophelimus spp. | 1930 | Minor - serious | Nil |

| Paropsis charybdis | 1916 | Moderate - very serious | Negligible - minor |

| Opodiphthera eucalypti | 1915 | Moderate - serious | Minor - moderate |

| Gonipterus platensis | 1890 | Moderate - serious | Negligible |

| Ctenarytaina eucalypti | 1889 | Moderate | Nil |

*Reviewed by T. Withers, Scion, August 2018.

What needs to be understood about eucalypt pests is that they each tend to favour certain eucalypt species. Although these "specialists" may cause only moderate damage to other species, they tend to favour one species or a small group of species, which they can severely damage. Some pest insects, however, are generalists, with any eucalypt species being a favourable host. In weighing up the risk of a catastrophic pest incursion occurring to a single plantation species, we also need to understand that there are exceptions to the rule, for example E. regnans (monocalyptus) is subject to beetle defoliation in Tasmania. Incidentally, possums also favour symphyomyrtus species and can cause severe browsing damage to trees of all ages, whereas monocalypts are not palatable.

Within eucalypt species, level of damage also varies for each pest. Once a pest arrives, genotypes can be identified that are generally resistant to that pest. This was evident when the brown lace lerp, Cardiaspina fiscella caused severe damage to E. saligna and E. botryoides throughout the North Island in the 1990’s, but some resistant genotypes of these species remained largely lerp-free. However, those genotypes are not necessarily resistant to the next pest incursion, an important consideration when attempting to breed for pest tolerance or resistance. This is important because although selections can be made that are resistant to a recently established pest, this approach does not necessarily proof those selections against future incursions (a generalisable resistance).

Biological risk is an important issue for the forest industry because of the long times frames involved. Risk mitigation must be considered in strategic planning and industry-good spending. By selecting pest-susceptible species for breeding programmes, we become locked into a perpetual cycle of protecting these species from pests into the future. Costly research into breeding pest-resistant lines holds significant risk in itself, because that goal is not necessarily achievable. Then, each additional selection criteria significantly adds to the cost of breeding. The other alternative, introducing biological control agents (i.e. natural enemies of the pest from Australia), is very expensive to get past the Environmental Protection Authority, as we know from the recent industry-led project aimed at introducing the Eadya wasp to control eucalyptus tortoise beetle. Then, following each incursion a specialist agent would be required to control it, which itself holds no guarantee of success. An existing plantation forest estate is required for industry to consider financially backing such work. For example Southwood Exports, who own over 10,000 ha of E. nitens in Southland might need to consider the impact that Paropsisterna beata will have on their E. nitens estate once it gets to Southland, and react by resourcing management of that pest, along with how to manage future damaging incursions. A research programme or fledgling industry does not have the luxury of being in that position.

Summary

It is clear from the historical evidence that insect pest intorductions tend to favour symphyomyrtus species and cause high levels of damage to species in that group. Therefore, should industry continue to invest in commercial development of those species, or refocus on the more pest-resistant monocalyptus group? There remains some unknowns and indeed there is some speculation that monocalypt eucalypts may be more susceptible to fungal pathogens not yet here, or recently arrived, such as myrtle rust. In weighing the importance of such risk factors, damage caused by fungal pathogen introductions in New Zealand has historically been a result of poor siting rather than being attributable to one group of eucalypts.

Research investment in developing "alternative" species to radiata pine has historically been at very low levels in New Zealand, which means that delivering the lowest hanging fruit, the lowest risk outputs to growers should be the focus of research efforts, with only well informed decisions made, that take into account biological risk.

Appendix 1: The history

Eucalypts have been planted as a timber crop for well over 100 years in New Zealand, and in other parts of the world for much longer. During the 20th century much interest was generated and plantation trials undertaken throughout the world because of the need for hardwood fibre and the dwindling natural hardwood forest resource. It became clear that Symphyomyrtus species produced the fastest early growth and were very adaptable to a range of climatic and soil conditions. Like every other country, here in New Zealand we started with blue gum (E. globulus) because it grew really fast and was adaptable, being a symphyomyrtus species. Before long (in 1916) the Eucalyptus tortoise beetle (Paropsis charybdis) arrived. This was an omen for what was to come, a plethora of insect introductions from Australia that target eucalypts.

Currently, with continued growth in global trade, we are finding that New Zealand is no longer unique in being subject to eucalypt pest introductions from Australia. What we have learned (or should know by now), most other countries are yet to learn. Globally plantations are dominated by fast-growing symphyomyrtus species and these continue to be selected for even faster growth. It's the story of the tortoise and the hare. The super-species, the southern blue gums, the red gums, the eastern blue gums... all symphyomyrtus and the fastest growing hardwood species on the globe, are bug fodder. Now, as a result of unfettered global trade, devastating Australian pests are arriving in these industrial plantations.

Luckily most growers here in New Zealand gave up on symphyomyrts years ago. I say luckily because New Zealand growers are unwittingly ahead of the rest of the world in our understranding of Eucalypts. So what is our understanding?

- Symphyomyrtus species are favoured by pests. This includes insect pests and possums.

- Most class 1 durable species are symphyomyrtus.

- Monocalyptus species are not favoured by pests and grow well in New Zealand despite the large range of Eucalyptus pests present here without their natural enemies.

- Symphyomyrtus species are better adapted to soil with poor drainage than monocalyptus species.

- Monocalypt species have similar soil requirements to radiata pine and are equally subject to soil diseases.

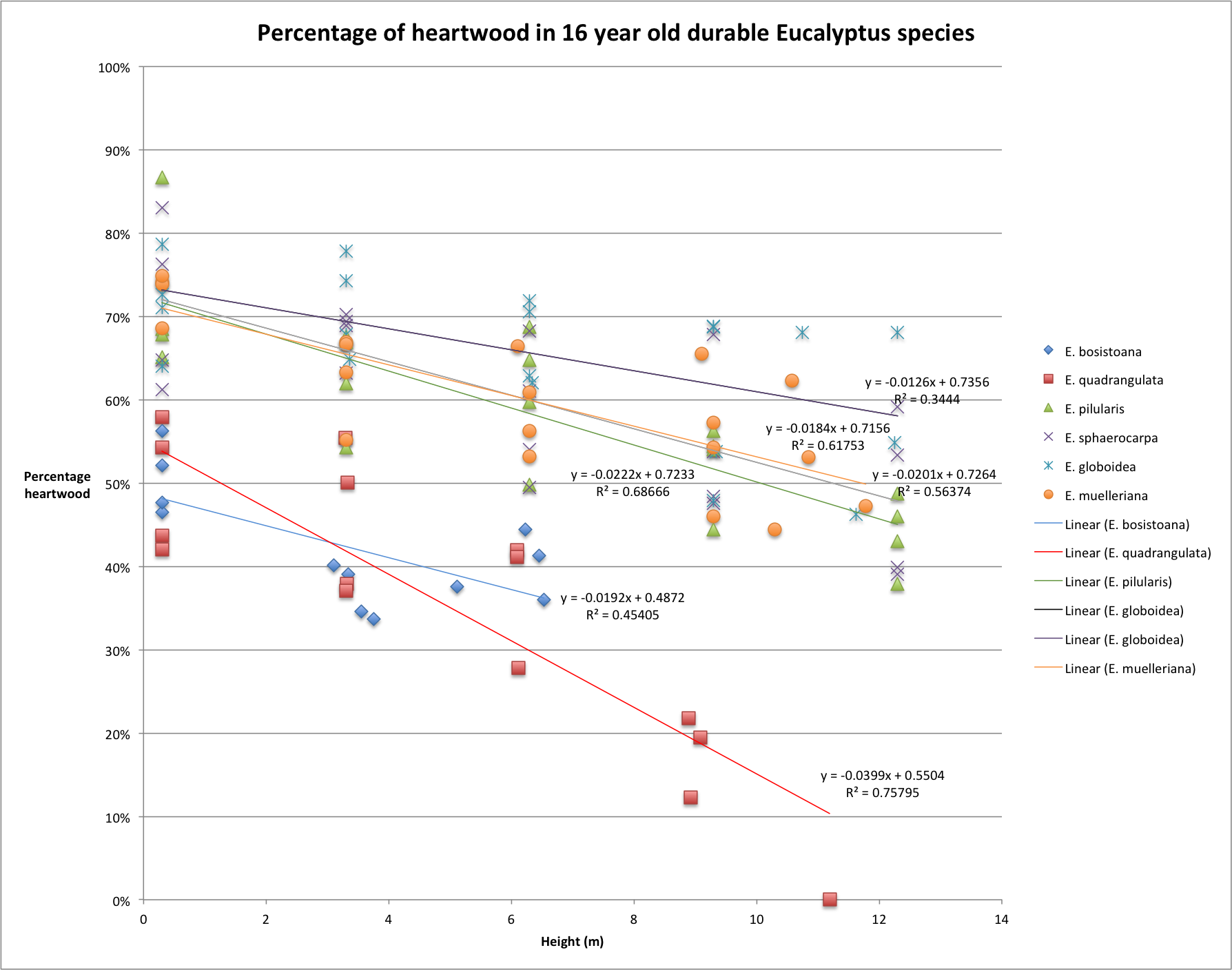

- Heartwood content is much higher in monocalyptus than symphyomyrtus species.

Disclaimer: Personal views expressed in this blog are those of the writers and do not necessarily represent those of the NZ Farm Forestry Association.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand

One post

Post from McNeill Trust on August 17, 2018 at 7:47PM

Add a post