The spike in harvest by woodlot owners - Coming sooner than you think

Chris Goulding and Hamish Levack, New Zealand Tree Grower November 2012.

Most farm foresters and the non-corporate small-scale forest owners are now aware that there will soon be a rapid rise in the number of forest stands available for harvest at about the same time they were thinking possibly of selling their logs. This rapid rise will be followed by a sharp drop, causing a spike in the volume of wood which is ready for harvest.

The spike is due to the short-lived, very high levels of new planting in the 1990s, mainly carried out by farmers and small-scale forest investors. The land planted is in small blocks but while it is often on the poorer parts of the farm, is still likely to be inherently more productive than that of the typical large-scale industrial forest. In some cases, where there had been a history of fertiliser use, this productivity is more than double the national average of the mean annual increment of 17 cubic metres a hectare of the stands currently being harvested.

On the other hand, the stands of trees may not have been professionally managed, perhaps with damage from stock, gaps in the canopy, subsequent mortality and varying degrees of log quality. However, radiata pine in particular, is reasonably tolerant of neglect and the trees still continue to grow while the owners are sleeping.

Forecasting available harvest

Forecasts of wood availability were carried out occasionally by the Forest Service, its successors the Ministry of Forestry, the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry and now the Ministry for Primary Industries. The most recent national forecasts are those of March 2010 following publication of a series of regionally-based forecasts. These separate the large-scale forest owners owning over 1,000 hectares from the small-scale owners.

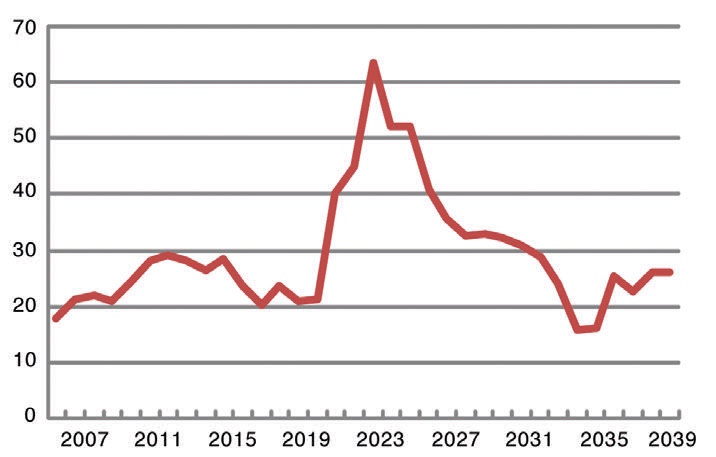

Market conditions, the intentions and the operations of forest owners determine the actual volume of wood harvested in any one year. Therefore the forecast exercise modelled several options to demonstrate a range of potential wood availability. The option termed Scenario 4 is often considered a probable indication of what may happen. This depicts a smoothed but steep rise in the national wood availability from 25 million cubic metres a year in 2019, to 35 million cubic metres a year a couple of years later. This increase would last until 2034, to be followed by a decline.

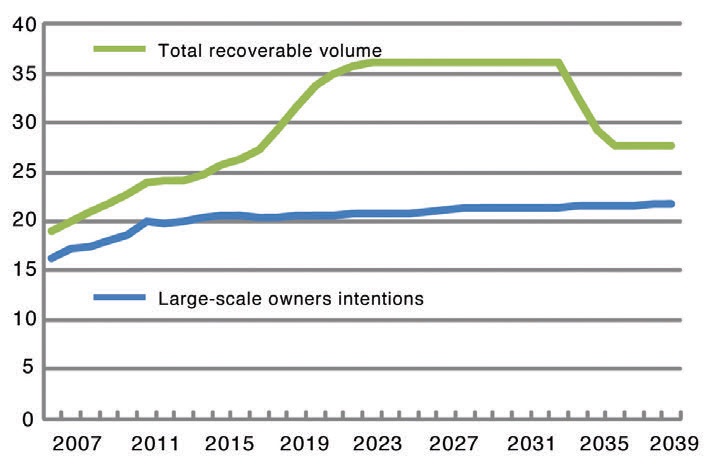

The forecasting exercise used the planned harvest intentions from the large-scale owners but it was uncertain of the intentions of the small-scale owners. The following graph shows the wood availability if all the small-scale owners harvest their stands when the trees reach 30 years of age and the large-scale owners at their planned levels.

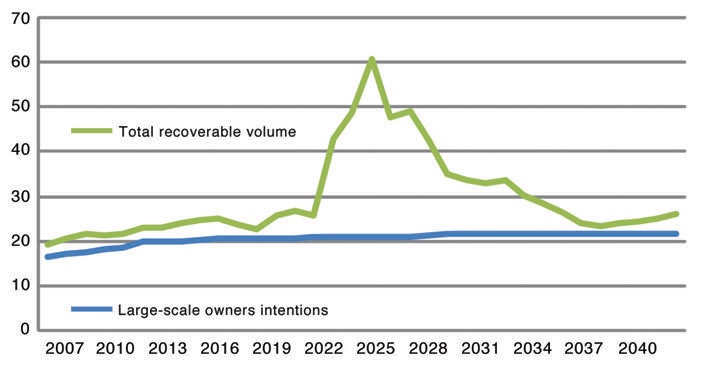

The next diagram shows the underlying issue which is what would happen if both large-scale and small-scale owners harvested their stands at 30 years, assumed to be the optimum rotation age. The volume profile which results is very unlikely, but shows the underlying pressures of potential over-supply in the short term.

The wood availability increases to 40 million cubic metres a year in 2022, peaking at 63.5 million cubic metres a year in 2024 before dropping sharply. The small-scale owners’ harvests could come on-stream dramatically, rising to 22 million cubic metres a year in 2022. This would be an increase from around six million cubic metres a year over the preceding three years, a four-fold increase.

Unknown area of forests

There are few reliable statistics on New Zealand’s small-scale forests, unlike those from the large-scale, professionally managed forests. The net stocked area of small woodlots is not known with any reliable level of precision. The National Exotic Forest Description data on them is compiled from returns on survey forms sent every second year to 1,820 owners who have between 40 and 999 hectares. These survey forms are completed by the owner to provide a hopefully accurate estimate of net stocked areas.

The National Exotic Forest Description data on owners with less than 40 hectares is based on the 2004 AgriQuality, now AsureQuality, survey. From 1992 to 2006 it was apparent that survey returns were missing significant areas of new planting. To put this right, annual surveys of nurseries converted reports of seedlings sold into estimates of hectares of new planting. This assumed a standard number of trees planted, subsequent mortality and tree stocks sold but not planted, and accounting for the number used in replanting the estimates of harvested areas. During the years of the small woodlot planting boom of 1992 to 1999, this adjustment was in excess of 15,000 hectares each year.

The year 2022 is only a decade away and the scenarios were modelled using average yield tables. Many woodlots on former pasture land with a history of some fertiliser application have more volume per hectare than in the large- scale forest. The individual trees will be growing faster in diameter and maturing earlier. A well-managed woodlot − well managed may mean little more than well sited, well planted, keeping the stock away and not thinned too heavily − may mature five or six years earlier than the 30 year rotation expected. In other words, this would be within the next few years.

Small-scale forest owners in other countries

In other countries where farm foresters produce a significant proportion of the harvest, forest management associations provide harvest planning services and a modicum of yield regulation. However, owners generally harvest when their trees are mature and when they require finance. In Sweden, the so-called Volvo planning method is when you need a new Volvo, you harvest some trees.

There is a range of ages within which is the optimum time to harvest, all other things being equal. New Zealand’s range is much narrower than in Europe. If the trees are too young log quality will be poor, too old and the large end diameter will be too big for the more efficient sawmills. Many owners here will be first-time sellers of timber.

Imagine an individual farmer trying to persuade a purchaser who has more than enough supply to offer a high net price. It is like asking a plumber with a full order book to quote on a small home job. Under such a scenario the forest owner is unlikely to realise the full value of their trees.

The Scandinavian option

Smoothing by market forces alone is unlikely to provide the best cash return to the small-scale grower. Would regionally-based forest management associations work in New Zealand as they do abroad?

Scandinavia has a long history of forest management associations dating from the 1930s. In southern Sweden, Sodra is an association with 58,000 members. Its objective is to help the forest owner members run a profitable forestry business. From its beginnings as a cooperative selling the timber of its members, it now owns three pulp mills and 10 sawmills. In 2009, despite the global crisis, it paid its members a dividend equivalent to $75 million. As well as providing domestic and international markets, its members are certified with both PEFC and FSC.

In Finland there is a hierarchy of regional forest management associations, the first originating in 1907, with membership now legislated by government. It is compulsory to join giving an owner voting rights, but it is not compulsory to participate further, although most farm foresters do. Each regional association employs a small number of professional staff. There are training and education days available to all. For an additional fee, an owner can request help in marketing, harvesting and silviculture.

A separate organisation, Metsaliitto, could be regarded as the equivalent of the Fonterra of Finnish forestry. It was formed in 1934 when the ‘intention was to invite forest owners to sell their logs through it’. Metsaliitto is now a large multinational wood-processing company owned by 131,000 small-scale forest owners, half the private forest area of Finland. Its mission is to competitively procure, market and upgrade Finnish wood at its own production units so as to enhance the value of its owner members’ assets. In 2010 it had sales of €5.4 billion with 25,000 employees in 12 countries.

The relevance of the European experience

Last year, the northern European countries, where the forests are owned mainly by the small-scale forest owner, displaced New Zealand as Australia’s chief supplier of wood product imports.

The New Zealand farm forest sector should not think of itself as small and insignificant. The smoothed annual harvest of 36 million cubic metres is 70 per cent of the size of the current Finnish harvest, with the New Zealand small-scale owner providing 40 per cent of the nation’s future supply. Will the small-scale forest owner benefit financially from their combined strength to the extent their European equivalents do?

We are different

Small-scale forestry in New Zealand differs in several ways from that in Europe. Different methods will be needed, at least initially, to achieve a sustainable and profitable harvest.

In New Zealand the small-scale forest owners have yet to get organised. The Ministry for Primary Industries estimates that there are 15,000 small-scale forest owners, but individual owners within regions do not even know each other. Even the total area of their forests within any wood supply region is not known with any certainty.

No public list of addresses of individual small-scale forest owners exists. It is thought that most of these owners are first-time forest investors with little understanding of good forest practice or of the potential benefits of joining a forestry cooperative. On the other hand, in Europe, it is usual for a family to have owned its woodlot for several generations and to already be in a well-established, powerful forestry cooperative.

Cooperation needed

European countries are not facing a wood supply spike to the extent in New Zealand. Here, small-scale forest owners may need to cooperate to spread their tree harvest age from 25 to over 35 years. In Europe there is no pressure to modify when an owner decides to harvest, except the owner’s financial needs, regulated within an approved forest management plan.

The more uniform age-class distribution of small scale forests in Europe make it relatively easy for the free market to operate, and for competing wood processors to obtain a sustainable cut which provides the feed stock for their mills. Because of continuity of supply and work, contractors are able to keep down the cost of harvesting and delivery, with forest owner revenues maintained. Conversely, in New Zealand the highly skewed small-scale forest age class distribution will result in the potential for much higher costs, lower owner returns, and reliance on exporting logs rather than processing domestically.

Conclusion

To transform the New Zealand small-scale forest wood availability spike into a sustainable yield, some of the trees must be left to grow very much older than the average harvest age of 35 years. Alternatively, new planting rates could be increased to about 20,000 hectares a year during the next decade and the small-scale forest owners cooperate in selling their wood and spreading their harvest ages to between 25 and 35 years to achieve a wood availability profile similar to that shown below.

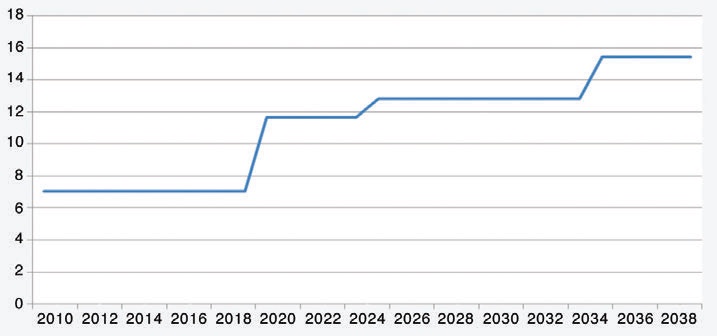

Last March the New Zealand forest and wood products industry strategic action plan was launched. It aims to achieve $12 billion a year of national export earnings from the forestry sector in ten years’ time, instead of the current trajectory of about $6 billion a year. It would do this by domestically processing the increase in annual wood supply of the smoothed 10 million cubic metres a year which is coming available.

Almost all the potential 10 million cubic metres a year which is coming on stream is owned by small-scale forest owners. Therefore equitable ways will have to be found to encourage the cut to be spread. Without the clear expectation of a sustainable wood supply, investment in new wood processing will not be forthcoming and the $12 billion target will not be reached.

Part of the strategic action plan refers to developing options for sustainable and mutually-beneficial wood supply agreements between growers and processors, and including small forest growers. Another part of the plan refers to facilitating collaborative business models that lead to industry co-operation. These are very sensible proposals, but nothing will happen without a serious and concerted effort by the forestry sector with the full support of the Ministry for Primary Industries and government. We need to −

- Identify, involve and educate the 15,000 small-scale forest owners

- Aggregate small-scale forests via some form of cooperative

- Set and achieve appropriate regional new planting targets.

Chris Goulding is a Principal Scientist at Scion, and Hamish Levack is the owner and manager of Levack Forests.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand