Recognising site quality for forest productivity

Michael Orchard, New Zealand Tree Grower November 2010.

If we were a big organisation looking to buy the optimal piece of land for forestry production, we might go to the fertile pumice lands of the Bay of Plenty or ash country of Taranaki. There we could laugh in the face of the fertiliser salesman, as we could in Poverty Bay, although occasional tropical cyclones and erodable soil slipping from under the tree roots would be a danger.

Similarly we could go to Canterbury, covered in fertile loess over a shingle base, or similarly along any major river in New Zealand with recent alluvial silt deposits. However, we might first need the big soil-ripping tynes, or to ensure our stop banks were in order, and we would have to worry a bit about fire, drought and little furry pests.

Important points

For any land use, including forestry, there are many important criteria to consider. These include −

- Availability of skills and labour

- Knowledge of establishment techniques and management

- Potential species for the site

- Availability of good roading materials and machinery

- Ease of logging

- Future processing plant availability

- Distance to the mill and markets

- Regulations of the local territorial authorities.

There will always be potential competition from other land uses, depending on the state of the economy at the time. Some regions are just natural forestry areas. These include the West Coast and Northland, as well as just about anywhere that there is good rainfall. Native forests have been growing there successfully for at least 10,000 years, mostly without disease and pestilence, and will continue to do so. However, the high rainfall has meant some of these soils have become compacted and impoverished, often with iron pans forming.

Site index

A forestry technical measurement of site productivity is the

site index. The site index of a stand of trees is defined as the mean top height or the mean diameter of the 100 largest trees per hectare, at a given reference age. This is 20 years for radiata pine and 40 years for Douglas fir. Other reference point systems could be developed internally for West Coast conditions and tree ages.

The site index is an easily measured estimate of productivity but relationships may vary between species and from region to region. Site indices for radiata pine may be broadly classified as ranging from poor at 22 metres, through to good at 35 metres. The productivity of a stand can be increased by cultivation and fertiliser, but may be decreased by the passage of heavy machinery.

In earlier times both the Forest Service, and private companies would have had site index rankings for all their forests often by applying averaged data to soil map typing, and would have used these for internal tree management planning, and new land purchase decisions.

Good for forestry

For successful exotic forestry, just as for farming, these impediments have to be overcome. For native species the trees just keep on growing, with a little help from 1080 and similar products to keep possums at bay. It is well known on the West Coast that if you keep fire out of a native block which may have been heavily harvested, then it will naturally regenerate to its original forestry type.

Even if the economics of harvesting has meant a probable reduction in planting of pine by the government, then such hill country areas are eminently suitable for carbon farming. On more of the front country, they will be managed for high quality timber production as long as they are wind-firm long rotation species such as Douglas fir, redwood and cypress. They could be mixed in with deciduous hardwoods and native timber species, then managed on continuous cover forestry principles.

Many of these opportunities will be on private farms as that is where the only real land banks remain.These will be on the periphery of their core farm areas such as wet sites, terrace sides, back hill blocks, shelterbelts, or even along streams in conjunction with native under storey species. These zones will be most under pressure for planting to meet clean stream accords. Many farms on the West Coast have sizable areas of regenerating or semi-mature indigenous forest that could be integrated into this process.

The following examples have been designated good and lower quality sites for the purpose of comparing biological productivity within the West Coast. It is important to note that with its deeper soils and wetter peat areas the good quality site will be the most expensive for road construction and harvesting, as they may require hauler use with gravel to be trucked in. The low quality site, where rotation length will probably have to be longer on an old rocky glacial moraine, will be cheaper and easier to log by ground based machine.

Good quality site

This seven hectare Arahura site near Fox Creek was a deep peat flax swamp. It was originally failed wet farmland reverting to gorse, sphagnum and weed species. We did not initially notice the tall and dense regenerating kahikatea forest forming the northern boundary when looking at the potential pine block area. While we were V-blading we could hardly see the top of the bulldozer over the short scrub, which appeared to be working in a deep brown soupy mess.

Occasionally it would get caught on an old podocarp stump and eventually we had to stop half way, because of the wetness, to dig an additional main drain and return to finish the job the following year. However once we saw the dense tall regenerating trees in the kahikatea forest block we knew this had to be a good site for growing more trees.

Some good radiata

This has certainly turned out to be the case, and the radiata pine in the photograph below is 14 years old and will become a wall of wood on its own. It looks dense because it is unthinned, although pruned and standing at over 600 stems per hectare. It is too difficult to thin now because of potential windthrow and cost, so we hope there is a good pole market around at time of harvest. The kahikatea mature pole stand is probably standing at between 1,000 and 2000 stems per hectare and there are some reasonable sized diameters on the bigger trees.

I estimate that the site index for radiata pine at this site to be over 30 and will carefully measure it at age 20 years. Between the main exotic and native blocks there are two drains and an access road. Along this, partly for amenity purposes, I thought it needed some longer rotation exotic coniferous trees to be compatible with the stature of the native forest edge. As a result some 13-year-old Chinese fir and coast redwoods can be seen as part of the species mix.

Good for native trees

Ecological site productivity is also related, and should be encouraged on all farm forestry properties. Native birds regularly use both sites, and there is a variety of fish, insects, spiders, fungi and special plants in among the exotics.

The natives have a rich forest understorey. In autumn the kahikatea trees annually produce large quantities of berries, and the forest becomes a cacophony of sound and pigeons soaring. In spring tui closely barrel through the pine forest in twos and threes, at such speeds you really need a hard hat, and the bellbirds enjoy the flax and eucalypt combinations.

In the younger exotic forest, fernbirds, moreporks and brown creepers have been seen, in addition to all the more common weka, fantails, tomtits, silvereyes and grey warblers, with pukeko in farmland next door. One day I may block off one of the drains in the upper reaches to recreate a wetland pond.

Lower site quality

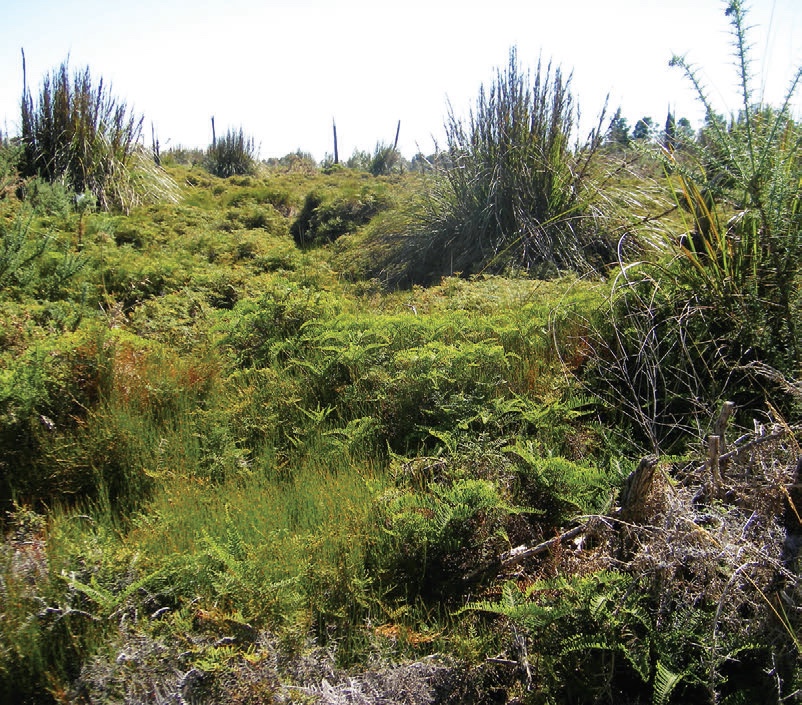

Farther up the road on our other 20 hectare joint venture site on the better drained hill soils, the gorse and scrub was over five metres high in places. The area was completely inaccessible until we carefully followed behind the blade of the first tentative bulldozer passes, and the lie of the land and eventual planting pattern could be determined.

The mixed podocarp forest on the hilltop had deep well-drained black forest soil, which extended out to the tall regenerating manuka stands under which many other young native plants were beginning to appear. But outside this area depleted soils and naturally poorly drained pakihi areas on iron pan or impeded grey clay base soils were very shallow and nutrient depleted.

Lower site index

As a result the trees we planted were much shorter at 14 years than on the good quality site. Canopy spread was less, so when fertiliser was applied it was partly taken up by the gorse and shrubland between the trees. In the longer term it will still be released to the trees as the gorse and understorey vegetation dies and rots away.

I estimate that the site index for radiata pine at this lower quality site to be under 25. But although productivity is lower and growth slower in comparison to the first deep peat soil type, access on the rolling pakihi and moraine hills is very good. There is plenty of rock for road building, and harvesting would be cheaper as it is all accessible to wheeled or tracked ground hauling machinery.

With lower fertility, it is standard to have wider spaced trees, to allow more root spread for each to take up their essential nutrients, so this site has been thinned to about 350 stems per hectare. Trees can be expected to be shorter and stouter at harvest, and growing in the rocky side slopes may be slightly more wind firm.

Better in eucalypts?

Nearby one wetland area was so deep in organic peaty material that the soil looked more fertile and discussion was held as to what more interesting production species might be tried there. Most species are generally more specific in their site requirements than the ubiquitous radiata pine. So Eucalyptus nitens was chosen for the flat and E. fastigata for the hill slope, both being reasonably frost hardy, along with some attractive amenity eucalypts around the perimeter.

Spacing for eucalypts needed to be much wider as the purpose is to grow large diameter trees that have reduced growth stress for milling. The intended use is for veneer or sawlog and pruning, especially of big branches, should be undertaken. Therefore the stands have been thinned to below 200 stems per hectare so that large crowns can develop to produce big trunks. The site is still poor so we have skinny trees, compared with the large volume eucalypt trees that we can grow on fertile lowland sites.

On the environmental side, eucalypts are favoured trees for native birds with tui and bellbirds often looking for insects under loose bark or feeding off nectar from the flowers. E. fastigata is particularly impressive, with great numbers of yellow flowers in season, attracting many insects, and feeding frenzies of fantails and other insectivorous birds. A large deep infertile swamp with different vegetation occupies the bottom of the basin on which all of the above trees grow around the side slopes.

Fertiliser application and spraying

All trees on the West Coast need regular periodic nutrient deficiency testing and fertiliser application of many essential elements, particularly phosphate, calcium, magnesium and boron. Even fast growing previously healthy stands can simply stop when nutrients run out. You begin to see thin canopy leaf density and dead branches on the lower stems just above pruned height, even though canopy closure has not occurred.

Often signs of yellowing or deformation of stems are clues in pines. This discolouring should not be confused with dothistroma or other fungus diseases which should be surveyed for regularly and treated.

Luckily we have very few introduced leaf browsing eucalypt pests on the West Coast. Although our native pinhole borer will attack trees under stress, eucalypts often kill them, so the timber is usually not degraded. Eucalypts under stress generally have red colouring of the leaves as nutrients are re- mobilised to be sent back up to the to growing tip, and often require extra slow release nitrogen fertiliser in addition to those other basic nutrients listed above.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand