Stop bugging me: Giving eucalypt pests the push

Stephanie Sopow, Toni Withers, Lindsay Bulman and Michelle Harnett, New Zealand Tree Grower May 2016.

Nibbling, noshing, chewing, sucking − Australia’s vast variety of eucalypts are fodder for a wide range of insect pests. With trade and weather patterns, many have made their way from their homeland to New Zealand where they threaten eucalypt trees planted in local parks and forests. Some, such as the eucalyptus tortoise leaf beetle, have been in the country for a century or more, others are recent arrivals with their presence only being noted in the last couple of decades.

The task of combatting serious threats to planted eucalypt forests falls to New Zealand’s forest entomologists, such as those at Scion, who can identify, monitor and work out ways to fight old and new pests, and try to anticipate what might pose problems in the future. These are some of their stories.

Keeping bronze bug at bay

The bronze bug Thaumastocoris peregrinus is a recently recorded arrival from Australia. It was first found in central Auckland in 2012. A sap feeder, its presence is concerning as it can lead to premature leaf drop, branches dying, and in severe cases, tree death.

Over 40 species of eucalypts have been recorded as hosts of bronze bug worldwide, but the most severely affected species in New Zealand so far appear to be Eucalyptus nicholii and E. viminalis, both popular amenity trees. With the exception of E. argophloia, the eucalypt species thought to be suitable for dryland hardwood production in New Zealand have not been reported as hosts so far.

In the autumn and spring of 2015, Scion scientists surveyed the North Island for sightings of bronze bug and found it had spread to Auckland’s North Shore and as far south as Hamilton, a distance of approximately 130 km. Bronze bugs were not found on its favourite hosts in Rotorua, Tauranga and Hawke’s Bay, but it is feared the pest may soon reach the Bay of Plenty region due to its ability to disperse. Another survey will be carried out in autumn this year.

Help find bronze bug

The 2015 findings, and earlier observations, have been recorded on the NatureWatch website. NatureWatch is a public forum encouraging citizen science. Anyone who notices bronze bug is urged to enter their sighting at www.naturewatch.org.nz under the project ‘Spread of Bronze Bug in New Zealand’ and help entomologists map the spread of the pest in New Zealand.

Autumn is the time of year when bronze bug damage to eucalypt trees is most apparent. Heavily infested trees can be identified from a distance by their rusty colour. The leaf discolouration is called winter bronzing. When bronzing is not visible, or for trees with foliage out of reach, infestations can often be confirmed by looking for clusters of black eggs on fallen leaves on the ground. This is a good way to establish the bug’s presence because both unhatched and hatched eggs are very visible.

There is a note of warning. If you come near infected trees be very careful not to accidentally pick up hitchhikers and spread the bronze bug further. It is good practice to spray clothing, shoes and even vehicles with household fly spray before leaving a confirmed site.

A bug-eat-bug world

The tortoise leaf beetle Paropsis charybdis was first recorded in New Zealand in 1916. With few natural enemies in this country, it is a ferocious pest of eucalypts. Females can lay up to 4,000 eggs in their lifetime and both the larval stages and the long-lived adults prefer the flush foliage of E. nitens, E. macarthurii and E. globulus.

Attempts have been made to introduce biological agents to control tortoise leaf beetle. An egg parasitoid was successful in reducing pest numbers for many years until a natural incursion of one of its enemies reduced its effectiveness. A ladybird has also been spread to a few parts of New Zealand, but this was never thought to be an agent that would solve the tortoise leaf beetle problem. Now, the potential of a new control agent that targets the beetle’s larval stages is being evaluated.

Biological control

Eadya paropsidis is a parasitoid wasp from Tasmania. It lays its eggs inside tortoise leaf beetle larvae. On hatching, the wasp larvae eat the beetle larvae from the inside out and eventually kill them. The wasp larvae then pupate and emerge in the following spring.

One of the first steps in introducing a new biological control agent is rearing it in laboratory conditions. The entomologists working with E. paropsidis knew this would be a challenge. During 2015 a small number of the parasitoids were successfully over-wintered. Daylight hours and temperature were manipulated in a high security containment room to mimic those occurring in the parasitoid’s native Tasmania. Then it was a case of crossing fingers and waiting.

The project team members were relieved to see a small number of the parasitoids began to emerge from over-wintering at the end of November 2015, synchronised with the emergence of their Tasmanian relatives. Although a ‘baby step’ in relation to the entire project, the successful over-wintering, as well as successful wasp matings in the laboratory, were breakthroughs for the team.

Testing the control

Another necessary step before releasing a new organism is to make sure that the control agent only attacks the target host. Over the next two years the team will be checking to see if E. paropsidis is host specific, or if it attacks other beetles closely related to the target pest, whether native or introduced for weed control.

This work has started using a combination of approaches. One is a forced exposure to either the target or non-target larvae alone. Another is a ‘two-choice assay’ with exposure to target and non-target larvae at the same time. Two beetles in the same subfamily as tortoise leaf beetle have been subject to screening so far, the tutsan weed leaf beetle Chrysolina abchasica, which could potentially control this weed, and the broom leaf beetle, Gonioctena olivacea.

The results are promising so far. In tests, female E. paropsidis tend to ignore both of these alternative species. Instead, they carefully and repeatedly search the eucalypt leaves and stalk tortoise leaf beetle larvae. The team are rearing all the target and non-target larvae to confirm these observations. An update on this research will be available on the NZFFA website later this year.

The work on E. paropsidis is supported by a Sustainable Farming Fund grant from the Ministry for Primary Industries with co-funding from NZFFA, Southwood Exports, Oji Fibre Solutions, the Specialty Wood Products Partnership and Scion core funding.

Very hairy caterpillar update

Arriving around 1992, the gum leaf skeletoniser moth Uraba lugens is now found from Auckland to Nelson. As well as reducing gum leaves to a skeleton, the caterpillars are covered in long hairs which can be intensely irritating to human skin.

Scion entomologists found that the parasitoid wasp Cotesia urabae was a promising biocontrol agent for gum leaf skeletoniser − see the article in Tree Grower, May 2015. The first wasps were released in 2011 in Auckland where they have become established. Further releases of wasps and gum leaf skeletoniser caterpillars infected with wasp larvae followed in other places around the country. Dr Toni Withers, the scientist leading the project, has just recently received confirmation that the wasp has become established in Napier.

The presence of C. urabae is good news for residents of suburbs such as Napier Hill. The summer weather has favoured the pest caterpillar, which has proliferated to such an extent that it is a health hazard in gardens and backyards with overhanging eucalypt hosts.

Invasions, incursions and infestations

It is impossible to predict what and when the next incursion might be. The only sure thing is that there will be new incursions of eucalypt and other plant pests, and that the number of establishing pests could increase with climate change and increasing global trade.

Forest biosecurity surveillance, monitoring insect traps and trees around ports and other high risk sites and inspection of imported goods intercepts many pests every year. However, nothing is fool proof. Ten forest insect pest incursions on eucalypts have occurred in last two decades. One of these was successfully eradicated. Improving forest biosecurity surveillance is another part of Scion’s work. The way biosecurity risk is assessed is being revised with the aim of improving early detection of new pests and pathogens.

It is more efficient to look for unwanted organisms in areas where they are most likely to establish. To this end, the Scion team are looking at the risk of pests arriving via pathways such as sea vessels, containers, dunnage, used vehicles imported from overseas, furniture and people to predict where the pests might first make landfall.

The pests being used as models in this work originate from Asia, Europe and the USA. While this may not seem particularly relevant to eucalypts, there is a real possibility that eucalypt pests could reach New Zealand from countries around the world where plantation eucalypts are grown. The bronze bug, for example, is found in South Africa, South America and Europe.

Predicting discovery

The aim is a surveillance scheme which detects the next incursion by predicting where along the pathway pests are most likely to be found. The Asian gypsy moth pest often enters on imported cars and is far more likely to be discovered in car yards than at a port or registration site. Knowing that, it is possible to work out where in the country it might be discovered. Perhaps predictably, the points of highest risk are around ports and urban areas.

Considering the highest risk areas, and the cost of forest surveillance around the country, it is possible to identify where surveillance efforts should be concentrated to get the best value from limited resources. The Kaikoura region provides a good example of how effort can be optimised based on risk. It is expensive to monitor forests around Kaikoura and the risk of exposure to Asian gypsy moth via a car yard in this part of the country is low. Therefore, it makes more to sense and cents to concentrate surveillance on regions where the risk is higher, such as Auckland or Tauranga.

Risk and cost

The forest biosecurity surveillance highlights that the major points of entry are air and sea ports, which are generally located near urban areas. This complicates the logistics of trying to eradicate pests using methods such as broadcast aerial spraying. The need to be able to deal with pest incursions in cities has led to a new research programme funded by Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment and led by Scion.

The overall aim of the project is to improve New Zealand’s ability to eradicate plant pests before they become established based on −

- Active surveillance to detect populations while they are small

- Developing alternatives to broadcast aerial spraying to reduce pesticide use and concerns from the public

- Understanding communities to communicate risk better and to involve residents in planning and preparation for eradication efforts.

The results of the research are also likely to lead to more efficient methods to manage already established pests and to improve the protection of native plants.

The project’s budget is $4.5 million over three years. This sounds expensive but must be weighed against the potential costs of a high risk plant pest becoming established, in term of lost production and the possible effects of other countries closing down trade due to concerns that exported products could be transporting the pest. Improving New Zealand’s biosecurity is estimated to be worth $2.5 billion.

Pest potential

Improved surveillance and detection methods at ports are all very well, but pests can be blown across the Tasman Sea. The westerly conditions suitable for trans-Tasman migration occur 20 to 30 times year. Australian moths, butterflies, other invertebrates and pathogens are arriving all the time. The most likely landing places are thought to around Nelson and the Marlborough Sounds, and near the Manawatu Gorge, Mount Taranaki and low lying areas north of Hamilton.

With climate change, some areas of the country are predicted to become warmer, others wetter, and more frequent and extreme weather is expected. The big questions are which pests might establish themselves in a warmer and wetter New Zealand, and how will those that are already here react.

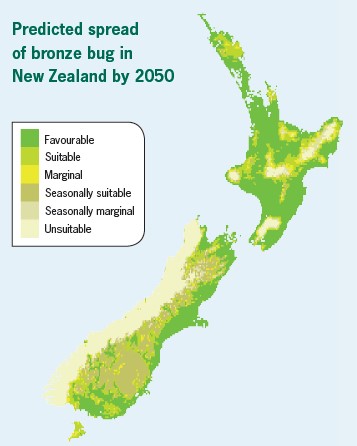

Indications of what might happen over the next century can be generated by modelling how particular species might react under different climate scenarios. Using bronze bug as an example, and conservative climate predictions, the results suggest that it has potential to establish throughout most of the North Island and in the northern and eastern regions of the South Island.

Not always a problem

Trying to anticipate which eucalypt pest could arrive next, and whether or not it might cause serious problems is nearly impossible. For example, tortoise leaf beetle, which is perhaps New Zealand’s worst eucalypt pest, is very rarely a problem in its native Australia.

Some clues as to which insects and diseases have the potential to cause trouble in New Zealand can be found in planted eucalypt forests growing outside Australia.

Beetles from the genus Trachymela, which are close relatives of tortoise leaf beetle, are pests in South Africa and California. Some species are have been reported in New Zealand but do not seem to be a serious threat, but considering that Australia is home to more than 120 different species of Trachymela, it is quite possible one or more could cause problems in the future.

On an optimistic note, an incursion and even establishment does not necessarily mean an insect is here for good. Odd-looking beetles reported on eucalypts by an Upper Hutt resident in 2012 were identified as Paropsisterna beata. A programme using targeted spraying was successful and the P. beata population was eradicated.

For the insects that do slip over New Zealand’s borders, the best protection is active surveillance and early detection. Owners of small to medium size forests, who know their trees and their land, are in an ideal position to spot new or unusual insects and other pests. Suspicious pests should be reported on the MPI hotline 0800 809966.

For more information on eucalypts pests contact forest entomologist Dr Toni Withers, toni.withers@scionresearch.com and for more information on forest biosecurity contact Lindsay Bulman, Science Leader Forest Protection, lindsay.bulman@scionresearch.com

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand