Options for changing the Cost of Standing Timber provisions

Howard Moore, New Zealand Tree Grower May 2016.

Sections of the Income Tax Act 2007 behave as a barrier to the aggregation of small forests. Aggregation would allow coordinated harvesting, continuity of supply and economies of scale, all of which would improve forestry sector returns, investment, tax flows, resource consent processing and environmental control.

At present the Income Tax Act treats standing trees as inventory, regardless of the fact that crop rotations in forestry occur over decades rather than the weeks or months of common items. Over such long periods, inflation and the time cost of money badly distort tax equity.

When standing trees are sold the seller must pay tax on the sales income while the buyer cannot claim a matching tax credit until the trees are harvested or resold. When immature standing trees are sold several years before harvest, inflation and the time cost of money combine to erode the benefit of the buyer’s tax credit.

The erosion of value creates a different expectation between the buyer and the seller. Calculations suggest that depending on the age of the forest, the buyer’s offer might be 40 per cent lower than the seller’s expected price assuming as, an example, that the forest is 15 years from harvest with inflation at two per cent a year and real cost of funds three per cent. It means there is little likelihood of agreement. While immature forests do sell, the market is thin, illiquid and not necessarily rational. This is not good for the sector or for the country.

The problem

About 14,500 different entities own forests in New Zealand. Around 90 per cent of these, approximately 13,000, have forests of less than 100 hectares. Because forestry is not really the focus or main source of income for these owners their blocks are scattered, of mixed quality and often planted on poor country. Despite this, their trees are worth a total of around $15 billion if they can be harvested.

At present, however, each of the 13,000 owners has to apply for their own resource consent, pay for roading, engage their own contractors and then take legal responsibility for their health and safety. After managing the stress of learning about and then actually doing this, they may find that total costs outweigh income from log sales leaving no return.

Poor returns from small forests have been widely experienced and are becoming common knowledge as a result of research published by the University of Canterbury. Unless grower returns improve, many small forests may not be cut and New Zealand would not realise the $15 billion of value and potential cash flow of what is now growing on marginal land. The carbon benefit of letting those forests get older and older, rather than harvesting and replanting, is a tenth of that. This is based on allowing for windthrow and fire, long-run carbon dioxide storage of 800 New Zealand Units per hectare and a nominal value of seven dollars a unit for the 265,000 hectares.

- To improve returns growers must reduce costs because they cannot raise international prices.

- The best way to reduce costs without compromising wages and safety is to look for economies of scale.

- Economies of scale can be obtained by aggregating small forests to operate them as a single estate.

- Aggregation of small forests is discouraged by the Income Tax Act.

There are at least four options for improving the situation.

Allow the buyer of standing trees immediate deductibility

The buyer and seller of standing trees would be treated equally if the buyer could immediately deduct the cost from his assessable income. The IRD is opposed to this because it would treat standing trees as being different from other inventory. It would also allow someone to claim a credit on the purchase of trees never intended to be harvested, and so avoid tax. These are both weak arguments.

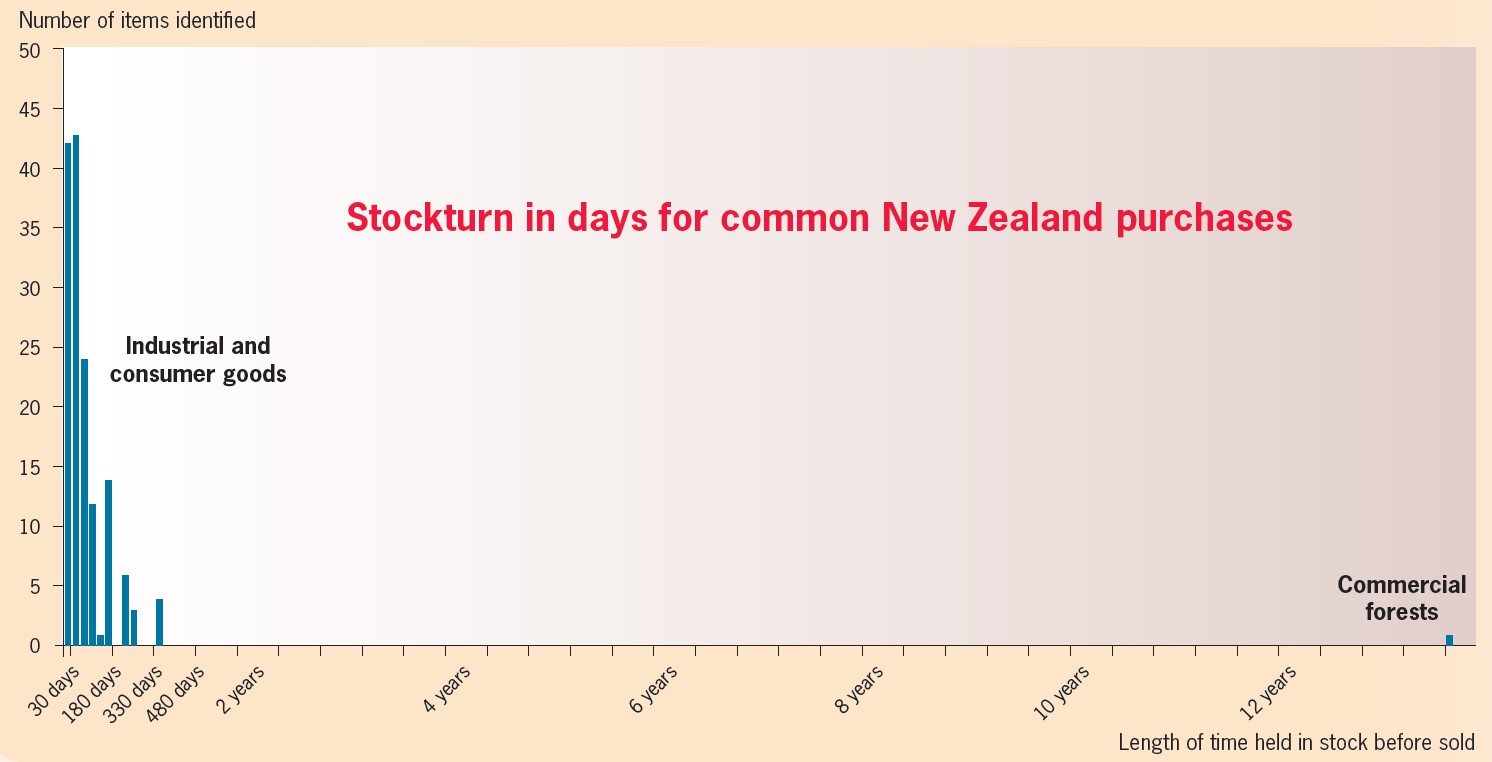

Standing trees are different from other inventory. In a US survey in 1998 the average time stock was held before resale was 30 days for retailers, 33 days for wholesalers and 45 days for manufacturers. For an immature forest sold after 15 years, the time is 5,475 days. A local analysis was done of 150 common items sold in New Zealand and as the graph below shows, in statistical terms, forests fall 60 standard deviations from the mean and clearly do not belong to the population of objects called inventory.

The IRD already recognises this to some extent, and has bent its inventory rules to allow the immediate deductibility of most costs associated with growing a forest. That variation, which the IRD admits is grudgingly allowed, is intended to encourage planting and management which would not otherwise occur. It is not offered or taken as a handout. The grower still pays 72 cents in every dollar and the tax deduction is returned many times over from the ecosystem services his forest creates, whether or not it is ever harvested.

Consumer or retailer

Few people buy and sell trees they never intend to harvest, but it can happen in estate planning where assets are bought and sold among family members. In such circumstances you might think it important to prevent someone from claiming a tax credit against a forest inventory they never intended to sell such as when their role was in fact a consumer buying a finished product rather than a retailer buying trading stock. Here the Act more or less works, as it seems reasonable for the IRD to charge tax on the transfer of inventory and allow the buyer a deduction on its resale. If no resale happens, then the buyer was obviously a consumer after all, and the deduction is worthless. If the buyer chooses to wait years to re-sell and his tax benefit is eroded, that is their choice.

However, this inventory approach ignores two important things. First, it costs money to maintain standing forest. The owner must protect it from fire, windthrow and trespass, keep fence lines and power lines clear, and pay the rates. No-one willingly takes on these costs for years without expecting some assessable return. Consequently, the likelihood that the buyer of standing trees will prove to be a consumer and not harvest them is actually remote.

Second and more importantly, the inventory approach ignores ecosystem services. While most of these are not monetised, privately owned or taxable, they still exist and are widely recognised. The owner of a forest holds an asset which prevents soil erosion, avoids pollution and creates habitat while improving water quality and landscape values. These benefits to the country have been estimated as worth over $5,000 per hectare each year. So, while the owner of a 100 hectare forest will get few benefits from the standing trees, the taxpayer may receive the equivalent of $500,000 a year in services.

That wealth transfer, from private investment to public good, is recognised under the Emissions Trading Scheme, the Afforestation Grant Scheme and the Sustainable Land Use Initiative. Here, both the Ministry for Primary Industries and the IRD encourage growers to establish and manage forests which might not be harvested. Not only does the IRD allow the growers to deduct the costs of these, but the Ministry for Primary Industries offers incentives by way of grants and carbon credits.

Out of step

How can anyone buying a forest that will not be harvested, such as a protection forest, be regarded as a consumer of the trees? Seen in this wider perspective, the Act’s inventory approach looks simplistic, clumsy and badly out of step with today’s realities.

Allowing immediate deductibility on the sale of standing timber might result in some people claiming tax breaks for forests they did not intend to harvest. But that would not be evil. In effect, it would treat them exactly the same as if they were the ones who had planted the trees in the first place. A fully equitable policy would be that the one who held the trees and provided the benefits got the tax deduction, and when he sold, they paid. This policy is simple, workable and updates the Act by explicitly recognising the benefits to the country of standing forests.

A variation of this approach was suggested by Copeland in 2012, when he proposed that the buyer might apply for the seller’s tax payment as a refund, once that payment had been received and processed by the IRD. That would give the IRD an opportunity to request and scrutinise the details of the sale, and decide whether or not it agreed to the refund.

Charge no tax on the sale of standing trees

Following from the above, you might eliminate income tax on any sale of standing timber, so that neither seller nor buyer had to declare the transaction. The deduction for planting and management would remain, together with tax on the income from harvesting, but any intermediate transaction which did not affect the forest, such as simply changing the name on the title, would be ignored.

In this case standing trees would be treated as a special category of inventory, with no regard for changes of ownership during ‘work in progress’. Whoever planted the trees would get a tax deduction and whoever harvested them would get a tax liability. It would not matter if they were different people. This is not a radical idea. It is how the IRD treats GST in the sale of a going concern.

The IRD might argue against the idea on fiscal grounds, because it would lose tax revenue on the intermediate sale of standing trees. However, this is an unpredictable figure which is not budgeted, and the IRD would lose nothing but windfall gains made at the growers’ expense. If it did try to quantify this, its calculation would have to acknowledge that the income tax lost would be offset by reduced deductions available to the owners on harvest, and even if it did forego some cash flow it would not lose tax over the forest rotation. Its calculation should also take into account the costs of enforcing the present Act to ensure that standing trees are sold at fair market valuations.

Charge no tax if there is no change in beneficial ownership

As a variation on the above, it could be argued that the IRD would lose nothing if it allowed forests to be aggregated tax free when beneficial ownership was preserved. For example, when a group of owners formed a company or cooperative to buy their forests at valuation for shares, or exchanged partnership shares for company shares. They could then run their forests as a single estate and achieve economies of scale without any third party.

Viewed from a distance such an operation might look like the owners were simply cooperating, rather than legally combining their assets. Indeed, the purpose of adopting a legal structure would be to formalise cooperation amongst members − setting common goals, timetables and protocols for resolving disagreement rather than to encourage cooperation by using a central manager to impose decisions. Because the owners could achieve aggregation and cooperation without a legal structure, why should they incur the ‘cost of standing timber’ provisions for making it formal, and adopting an enforceable set of rules? It is not the intention of the Act to discourage transparency and good business practice.

Proxy sale that avoids passing title

If none of the above were acceptable to the IRD, forest owners might use a fourth option. This is to avoid the ‘cost of standing timber’ provisions altogether by selling a proxy for the trees rather than the trees themselves. As the proxy is simply a financial instrument, it falls under a different section of the Act.

Still under discussion, the proxy would work like this.

- A buyer wishing to aggregate forests for economies of scale approaches the owner of an immature forest.

- Assessing the forest, they offer to buy the cheque that he believes the owner will receive when they sell the trees at harvest.

- The price of the cheque is the owners’ expected nett return at harvest discounted back to the present day, calculated in the same way as if valuing the forest.

- Obviously, the price of the cheque is similar to the sale price of the standing timber.

- Along with the promise of the future cheque, which is based on the sellers’ nominated harvest date, the buyer obtains the right to determine when the trees are cut, within an acceptable period each side of the nominated date. This gives some flexibility in harvest scheduling.

- The buyer secures the promise of the future cheque and harvest flexibility with a contingent ‘forestry right’. Being contingent, the ‘right’ does not incur the ‘cost of standing timber’ unless and until it is exercised on default of the forest owner.

- After completing a number of such purchases the buyer then holds the paper until the first forest matures.

- The forests are harvested by their owners on a schedule determined by the buyer, who receives the harvest proceeds from the owners as agreed.

- The forest owners are responsible for their own income tax following harvest. The buyer, who has taken the market risk that log prices have risen or fallen over the period, is responsible for income tax on the profit he has made on his receivables.

With suitable contractual arrangements, each preserving the owner’s title to the trees, the aggregate forests might be managed as an estate and achieve economies of scale.

We are told that this ‘forestry derivative’ would fall under the accruals regime of the Act. The buyer would pay tax annually on the appreciation of the receivables, which would rise in value as harvest approached.

Conversely, the seller or forest owner would claim a matching annual loss, which would reducing the final tax bill on the full nett harvest revenue. These matching tax streams would, of course, cancel each other.

Conclusion

The author fully supports the idea of a robust, simple and fair tax system which applies equally to all sectors. The provisions for the ‘cost of standing timber’ in the Income Tax Act however do not produce these values. They are clumsy, unfair and badly out of step with the government’s approach to land use.

At present they act as a barrier to the aggregation of small forests, reducing grower returns, investment, tax flows and national benefits. Small and logical changes to these provisions might remove this barrier allowing the sector to make a greater contribution to national well being. These changes should be considered under the IRD’s current programme for ‘Making Tax Simpler.’

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand