Leaving the ETS - Potential problems for owners of post-1989 forests

Ollie Belton, New Zealand Tree Grower May 2014.

International units have ruined the New Zealand carbon market. Ironically these same cheap units have also allowed many forest owners to wipe their carbon debt for as little as 25 cents a tonne by leaving the scheme. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, by June 2013 only around 190 of the approximately 2,800 registered post-1989 ETS participants had left the scheme. However since then, that number has grown considerably and no doubt will increase until May 2015 when the foreign credits will be banned from New Zealand.

Many forest owners are choosing to opt out of the ETS completely. Some have had enough of carbon and want no more to do with a scheme they regard as bureaucratically complex and a failed environmental policy. Others have harvest dates approaching and see no point in re-joining and having to deal with carbon liabilities and the associated administration. But for the most part, those leaving are immediately applying to re-join the ETS and earn carbon credits again from 1 January 2013 onwards.

In the process of re-joining, a number of people have encountered difficulties, with the Ministry for Primary Industries rejecting areas even though they had previously been registered. MPI explain that this is due to acquiring new aerial photography to assess applications.

Improved mapping is a welcome development as eligibility is an area of concern which was covered in the February issue of Tree Grower. MPI have said that updating their imagery ‘provides an opportunity to improve mapping accuracy, clarifying carbon entitlements and liabilities.’

Definition of an eligible forest

The MPI’s aim in assessing a forest application planted after 1989 is to determine whether the land is eligible and that it was not in forest in 1990. In this context, forest means woody vegetation which covers at least 30 per cent and consists of tree species capable of reaching five metres or more in height at maturity under the land management practices and environmental conditions prevailing.

This definition excludes gorse, broom and other scrubby species. It also excludes tree species which have not yet reached five metres in height and never will because of land management or because of the growing conditions. For example, in some regions such as exposed montane environments, manuka can never grow to five metres. Another common example is where areas of young bush are within actively farmed paddocks and subject to a history of regular regeneration and clearance before reaching the five metre height threshold.

Problems arise where MPI’s historic satellite or aerial imagery show up dark patches which could be vegetation around the year 1990. The onus then falls upon the applicant to prove the land is eligible.

Is the hurdle set too high?

The best evidence is historic aerial photography which can show with sufficient clarity that the land was not in forest. In one recent case, MPI initially rejected 30 per cent of a re-application due to their newly acquired imagery showing possible vegetation in 1990. The forest had originally been accepted into the ETS in 2011 with 140 hectares, but on re-application in 2013, preliminary assessment was that only 98 hectares were eligible.

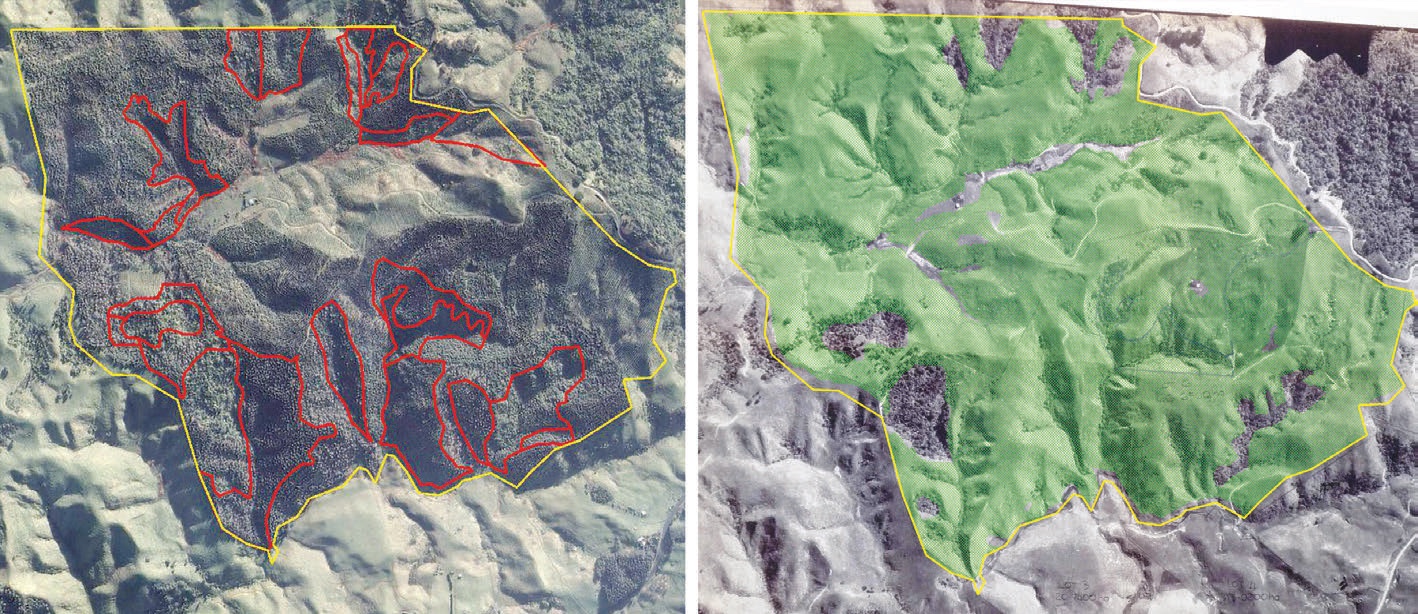

After reviewing MPI’s imagery it was apparent that most of the dark signatures were shadows and not forest, being on south-west facing slopes and showing up as such on recent aerial photographs. Fortunately the owners had an aerial photograph dating from 1985 which clearly showed the areas in question were predominantly rough pasture. In the end 137 hectares was accepted and re-registered.

In the photographs the map on the left shows areas initially disputed by MPI mainly on shady slopes shown by the red lines. The map on right is a 1985 aerial photograph with final area accepted shown in green.

Less clear-cut are cases where the history shows scrubby vegetation. Applicants need to prove the vegetation was either non-tree species such as gorse, or it was juvenile trees subject to land management that would have prevented them from reaching five metres. In these instances the evidential threshold required is high. Other than historic aerial photographs, evidence that MPI will take into account is limited and includes ground based photographs, planting and farming records. However, given that most of the forests in question were planted over 15 years ago, and may have changed ownership, this documentation can often be unobtainable.

One applicant remarked that without a time-machine to go back and take photographs of their block they had to give up the battle. Written information such as statutory declarations such as by previous owners who farmed the block, or circumstantial evidence, is given little or no weight. MPI could take a more pragmatic approach, especially in relation to forests planted on farmland. If young regenerating bush was present in 1990 but within actively farmed paddocks, the presumption should be that bush would not have been able to become a forest. To expect farm records going back 20 to 30 years to be obtained is a near impossible demand.

Inconsistent with Kyoto reporting

The government appears to have taken a more liberal approach at a national level to determine whether forest is pre-1990 or post-1989 for New Zealand’s Kyoto Protocol obligations and reporting under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. The governments’s land use and carbon analysis system tracks land use change and forestry for the years 1990, 2008, and 2012 and forms the basis for New Zealand’s claim for Kyoto units from post-1989 forest. One of the other cited benefits is to help verify land under the ETS.

There is a non-forest category called ‘grassland with woody biomass’ which covers areas where in 1990 ‘grazing/grassland management exists and the vegetation present does not ... meet the forest definition.’ According to the interpretation guide, evidence of grassland management includes ‘pasture in immediate locality, fence lines, cattle troughs, farm tracks and accessibility to farm grazing stock.’

This evidential approach to land management is less onerous than MPI’s and the discrepancy between the two is becoming more apparent. For example, a number of the post-1989 ETS re-applications recently rejected by MPI are classified as post-1989 forestland being ‘grassland with woody biomass’ in 1990 and planted forest between 2008 and 2012.

Arguably the land use and carbon analysis system is not always accurate on a property-by-property basis, and has a margin of error the effect of which is acceptable once averaged out at a national level. However, it seems unjust that the government can define a forest as post-1989 and claim the carbon benefits under Kyoto at a national level, while the actual owner of the forest is unable to register under the ETS.

Pre-1990 allocations and exemptions

A series of questions has arisen with regard to forests previously classed as post-1989 and now re-classified as pre-1990. Firstly, can these recently re-classified forests apply for a pre-1990 allocation of units to compensate for the loss land value? The cut-off dates for applying for units was 30 November 2011. As yet this question has not been tested, although it is unlikely given the deadline was absolute, with no allowance for extensions. A related matter is exemptions for pre-1990 forest land of less than 50 hectares. The deadline for applying was 30 September 2011, but there is provision for MPI to accept applications after this date on a case-by-case basis. MPI have said that forest previously registered as post-1989 forest that have been recently re-classified as pre-1990 are good candidates for a late exemption application.

What about non-exiting ETS forests?

The discussion so far has centred on owners of post-1989 registered forests leaving the scheme and then encountering problems when re-applying. But how does MPI’s new and improved mapping affect the classification of currently registered ETS forests which have no intention of exiting?

Experience now suggests that there could be quite a number of participants that successfully applied between 2009 and 2012 as post-1989 forests which would not pass MPI’s eligibility assessments today. Are these forests in danger of being audited and pulled up by MPI in the future? The good news is that this is unlikely to happen. MPI have advised that once land is determined as post-1989 eligible forest and accepted into the scheme they have no power to change this determination unless misleading or false information was provided. Nevertheless, are there possibilities where re-classification down the line is a possibility? Imagine a post-1989 registered forest is purchased with the intent of harvesting and conversion to pasture. Before the sale the buyer requires the seller to leave the ETS and repay the emission units. The new owner believes they have purchased a post-1989 forest unencumbered with carbon liabilities, are free to deforest. However, now the forest has left the scheme is it possible for MPI to re-classify it as pre-1990 and subject the new owner to a deforestation liability?

Obtain evidence and ask for advice

The continued mapping developments by MPI present risk for those leaving the ETS and planning to rejoin. However, the ability to re-classify a forest once it leaves the scheme also creates a legacy of risk for all present and future owners of post-1989 forests. If current or prospective forest owners are worried about eligibility and the possibility of re-classification to pre-1990 forest, they should try to obtain supporting historic evidence and talk to their consultant about those concerns.

Ollie Belton is the Managing Director of Carbon Forest Services Ltd, with over eight years of experience in providing services to carbon forest owners.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand