Trees for protection – native or otherwise

Jim Flack, New Zealand Tree Grower May 2013.

In geological terms, New Zealand is a young country and still growing. Tectonic plates grind beneath us, pushing the land upwards, while our maritime weather systems try to wear it down again. These are difficult conditions in which to keep productive soils in place, and as a young country our soils are very fertile and should not be wasted.

Fortunately nature provided a wonderful solution for most of New Zealand – the forest. Trees and plants of all sizes protect the soil from direct assault from the elements, slowing down the wind and the rain. Leaf litter slows the rain further and a net of roots from all the trees and plants bind the soil.

Many of the original forests have gone, but we have worked out their value in keeping our soils in place and many of us do what we can to replicate that effect where we need to. In this article we have a look at some of the methods for treating erosion-prone land and protecting riparian areas.

Water, wind and gravity

We are up against water, wind and gravity. Soil particles are round and can become mobile in water, particularly when rain is being driven into a hillside by wind, and gravity is trying to take it as efficiently as possible to the plains. In fact, erosion can be 16 times greater under pasture than native forest.

It is a typical scenario in our hilly landscapes. Fine sediment can surreptitiously sneak away in run-off, slopes can spectacularly let go and slide downhill, and soil can literally flow like a glacier – slow and relentless. Rivers are also constantly gnawing at their banks.What do we do about it?

Steep country with limited production

Steep country often struggles to maintain good pasture cover, particularly in drier years, leaving the soil partially exposed to the elements. Rain can wash away soil and fertility, and heavy rain can lead to slips. Some steep country has had 100 years or more of this sort of exposure and provides little income. There are still expenses, such as fencing, tracks, fertiliser and potential stock losses.

Many landowners have made the decision to retire this land from grazing and concentrate their efforts and expenses on more productive parts of the farm. In many cases, this increases overall production. Depending on access, the steep retired country can be put into plantation forest or encouraged to revert to native cover.

Radiata pine has the proven ability to bind soil on hillsides with its roots and works in about a 30-year cycle before harvest. Land owners may choose Douglas fir if a longer cycle, such as 60 years, is desired. If you want a permanent and maintenance-free solution which will last generations, then allowing or encouraging native vegetation to revert is the way to go. But bear in mind that whatever way you choose, the tree species must have the ability to establish roots and stabilise soils faster than they are eroding.

Hill country pasture

Productive hill country pasture is the mainstay of many farming regions, particularly on the east coast. We have lots of it and we need to protect the soils to keep this land in production for its communities and the country into the future. Ensuring that the soil is locked on to the hillsides also keeps it out of streams, rivers and lakes, where sediment can smother the bottom and nutrients can fire up all sorts of nuisance weed growth.

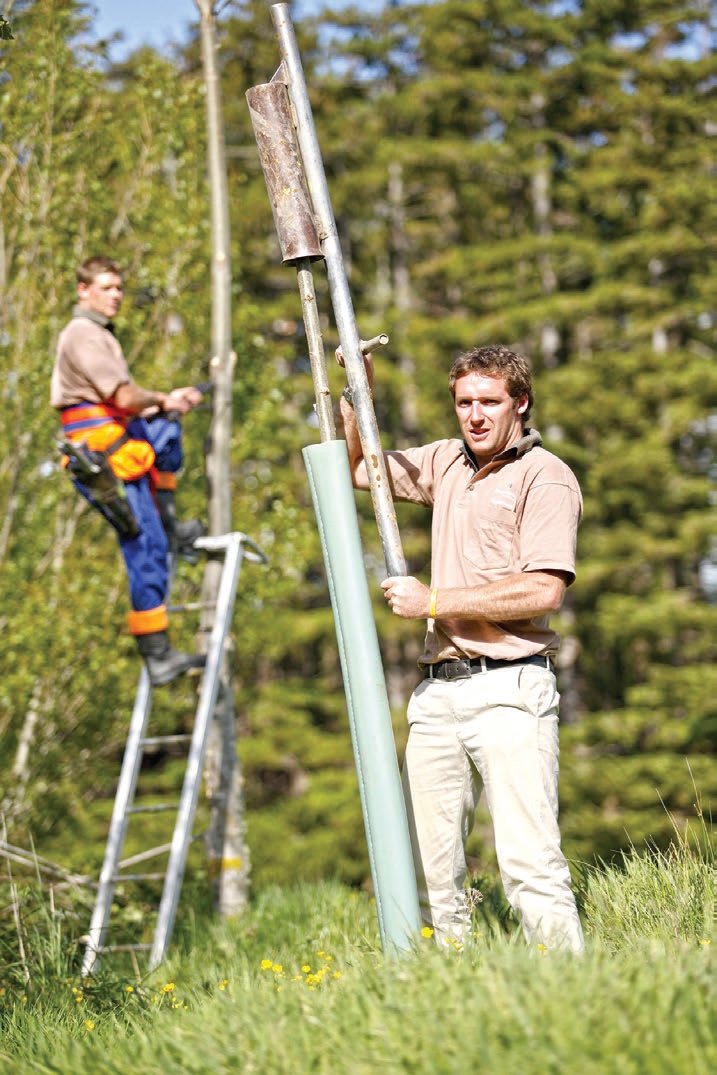

From the 1940s, farmers and soil conservators began experimenting with tree species with root systems which bind the soil and can be established on exposed hillsides without suppressing the pasture beneath. Lombardy poplar and silver poplar were early species used. The amazing ability of poplars and willows to establish root systems from a stem-cutting driven into the ground singled them out as the preferred option for treating erosion-prone land. They can be protected from grazing cattle, deer and sheep with a two metre long plastic sleeve that tears open and comes off as the trunk of the tree expands.

Fodder bonus

Space-planted at roughly 15 metre centres, about 60 to 70 stems a hectare, poplar and willow hold erosion-prone soils together. They keep these hillsides productive and sustainable for long-term grazing. They have the added bonus of providing a fodder crop if pruned while in leaf, with some farmers managing the tree shape and pruning regime specifically for this purpose. It can be a very useful practice during a drought.

Poplars and willows have traditionally been reliable at establishing the lower slopes, but were less effective higher up the slope where it is dryer. This made upper slopes difficult to treat without retiring the area from grazing until the trees had established, something that few land owners were prepared to do unless the erosion was dire.

Soil conservators experimented with varieties of eucalypts which could tolerate the drier slopes, planting them in wire cages and only grazing sheep in those paddocks until the trees were established and out of reach of cattle. This technique of poplars on the lower slopes and eucalypts higher up was particularly successful at curbing erosion on the property of Peter Gawith in eastern Wairarapa.

However, eucalypts were more time-consuming to plant and harder to protect from stock. Staff from the Greater Wellington Regional Council and the former Wairarapa Catchment Board tested many varieties of poplars and willows as a solution on the middle and upper slopes of Wairarapa hillsides throughout the 1970s and 1980s. They came up with a suite of varieties which will treat almost any pastoral situation. These varieties are propagated for harvesting poles at the Greater Wellington Regional Council’s 40-hectare Akura Nursery on the outskirts of Masterton to treat erosion-prone land predominantly in Wairarapa.

Protecting you from the river

If your property is bounded by a river which gets angry and likes to wander, you are probably going to want a thick buffer of vegetation between the riverbank and your paddocks. Many of these erosion problems around braided gravel rivers arise from squeezing the river into too narrow a channel and farming right up to the bank. The river wants to expand and meander and we want to farm as much of the fertile alluvial plains as we can.

For a cheap and quick fix to this problem the new varieties of less invasive willow are the answer. Booth and Moutere are varieties that are far less invasive than the original crack willow, which has clogged many a waterway. These varieties establish very quickly and bind the gravel, making it less mobile and erodible. Between the willow and pasture, landowners can encourage the reversion of native vegetation for an extra buffer and a bit of native biodiversity. As a rule, the more room you can give the river to do its thing, and the wider your vegetative buffer, the better.

Some of the best examples of vegetation stopping river erosion are in the forest parks around the country. There are complex communities of native trees and plants of all sizes along the side of the river banks. Each plant is managing in this site because it can handle most of what the river can send its way. This network does a god job of holding some extremely erodible country together.

Protecting rivers, streams and wetlands

Rivers and streams are often the source of erosion in themselves and on some properties this has been dealt with by leaving the native vegetation adjacent to the stream, particularly in hill country. Hardy and less palatable natives such as manuka tend to dominate, but if these areas are fenced, the full array of streamside natives from your catchment can appear.

Degraded water quality and fencing waterways have become a major environmental problem. Fonterra’s Clean Streams Accord was developed to tackle this concern and there is pressure for these measures to apply to all farming operations. Fencing and planting waterways means banks are less likely to erode and release sediment and nutrients into the water as stock cannot pug the banks. A good buffer of vegetation, preferably native, will intercept much of the effluent and fertiliser run-off from paddocks.

Planting waterways is a great opportunity to improve the environment. Catchment care groups and restoration societies are being set up all over the country. These riparian areas could provide important habitat for native plants and animals which have become scarce on the plains. Trees also provide good shade to cool the water for native fish.

Each region will have its selection of native streamside plants – olearia, coprosma, flax, cabbage tree, pittosporum, kowhai, ribbonwood, toe toe and manuka all leap to mind. Greater Wellington Regional Council has a 30-page booklet on how to plant a stream with natives.

It is recognised that fencing all waterways in hill country would be a massive and very expensive task. In response to the problem, Greater Wellington Regional Council, Federated Farmers, Beef and Lamb, Dairy NZ and Fonterra have developed a best practice guideline for grazing around waterways and it is available at http://www.gw.govt.nz/assets/Healthy-Waterways-Stock-Access-to-Waterbodies.pdf.

For medium-term erosion solutions to allow production to continue, it would appear exotic species are the way to go. But for permanent solutions which give the best protection to the environment, Mother Nature with her toolbox, honed by natural selection, will be the best choice every time.

Jim Flack is a former journalist working for Greater Wellington Regional Council.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand