Managing poplars and willows on farms

Deric Charlton, New Zealand Tree Grower May 2006.

There is a huge asset growing on our farms and in recent years it has been neglected. I am referring to the widespread and increasing population of poplar and willow trees that conserve erosion-prone pasture land and provide shelter and shade for farm livestock. Millions of these trees have been planted on farms in recent decades, but once they are well established, they have received little or no management and they then become a huge asset in more than one sense.

According to a farmer-led project in the lower North and South Islands, the time has come to manage poplar and willow trees for multiple gain. This project is funded mostly by MAF’s Sustainable Farming Fund (SFF) and is backed by regional council land managers and with technical support from Massey University, AgResearch, HortResearch and several relevant consultants (see the report here).

Clean timber and more pasture

If the poplars had been thinned and pruned regularly, they would have grown clean, knot-free timber, and the pasture understorey would receive more light and grow more pasture feed during summer. Well managed poplars and willows have better wind resistance and are therefore less dangerous for farmers and their livestock, reducing the chance of them blocking farm tracks, creeks, culverts and roads when storms occur. Pruning some well established poplar and willow trees on a farm every summer will also produce useful by-products – supplementary fodder for livestock grazing dried pastures and firewood for the farmer or for sale.

Practical farmer guidelines

The main aim of the project is to integrate poplar and willow trees into livestock farm systems for multiple aims including nutrient management, harvesting for supplementary fodder, and sustainable control of parasites in lambs. This is all in addition to maintaining the trees for their well known roles in conserving hillsides and providing shelter and shade.

The main components of the project are the development of a planting and management plan for poplar and willow on farms for various uses. Much of this information is widely dispersed, and so the experiences of farmers and land management officers is being collated and added to relevant new findings.

Using this information, a best practice set of guidelines for farmers and lifestylers is being developed. The most appropriate management will be defined for general and special purpose tree pasture systems, such as pollarding, coppicing and growing browse blocks.

Other options include establishing tree pasture browse blocks on sheep and beef farms with wet unimproved areas, to increase the feed supply and to enhance the farm environment.

Browse blocks for parasite control

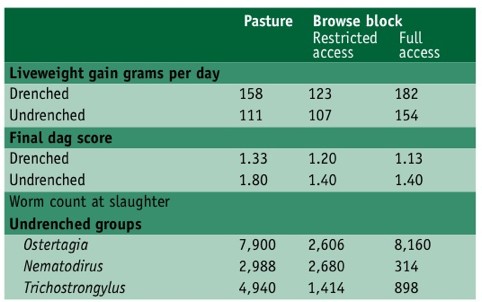

The potential of willows in a tree pasture system for naturally controlling parasites has been studied by looking at the effect of feeding willow on hogget reproductive performance. A trial at Massey University’s Riverside Farm, ran from early December 2004 until mid-March 2005 and involved three lamb groups, each comprising 60 weaned lambs.

They grazed either willow browse blocks all the time, grazed for a week on browse blocks and then three weeks on control pasture, or just grazed a ryegrass and white clover pasture during the dry summer period. All the lambs were drenched at the start, and half the lambs in each group were drenched every four weeks. The remaining 30 lambs were never drenched again during the trial. The drenched and undrenched lambs were grazed separately on each treatment and all groups were given weekly feed breaks in a rotational grazing system over 14 weeks.

The same feed allowance was given to all six groups, starting at four kilograms of dry matter per lamb each day and increasing to six kilograms by the end of the trial. Feed available in the willow browse blocks was a mixture of the low growing trees and unimproved existing pasture. The browse blocks were planted with one-metre willow stakes at 6,000 per hectare in 2001 on wet, rush-infested land that was unsuitable for pasture development. Since then the trees have noticeably dried the soil in the browse blocks and allowed good pasture to develop among the grazed low growing trees.

Reduced rates of re-infection

During the first half of the trial period all the herbage was green, but later on the herbage in the control pastures, including the restricted access group, turned brown because of the dry summer. However, the herbage growing among the browse willows remained green, and legume content was consistently greater than in the control pastures.

weaned lambs

Undrenched lambs grazing browse blocks showed some reduction in the burdens of the three main internal parasites. Parasite egg counts during the trial indicated reduced rates of re-infection in the lambs given full access to the willow browse blocks. Live weight gain was similar for drenched lambs grazing pasture only and for undrenched lambs given full access to the browse blocks.

The trial ran at Riverside Farm from early December 2004 until mid March 2005. Drenched and undrenched lambs were grazed separately on each treatment and all groups were given weekly feed breaks in a rotational grazing system for 14 weeks.

It therefore seems that growing willow browse blocks on areas of unimproved land offers one useful option for resolving the growing drench resistance problem. In addition, during summer and early autumn these browse blocks offer livestock a temporary haven from other pasture related livestock disorders, such as ryegrass staggers and facial eczema. When sheep are in these areas they have less exposure to ryegrass and dead matter that harbour the toxins responsible for these threats.

Costs and benefits

Another aspect covered in the poplar-willow project is a cost benefit analysis for tree pasture systems being undertaken by farm consultant John Stantiall of Wilson and Keeling. Analysing financial benefits of fodder trees can be challenging because the range of options is broad and there are different views about which costs should be included or excluded.

Options include poplar trees, planted specifically for fodder or mainly for erosion control, that are pollarded for drought feed, shrub willows grazed by sheep or cattle, and the concept of growing shrub willows for absorbing dairy effluent. The initial establishment costs, loss of grazing during establishment and labour costs are obvious factors to be considered.

To date, John Stantiall’s analysis suggests that fodder trees may break even in some situations provided that the labour cost is not included. The farm systems were initially modelled using information recorded from available trials and several similar scenarios were developed to investigate the impact of variables like the effective farm area planted in these trees. The model Stantiall used could be developed for farmers to use their own information and determine the economic benefits of tree planting on their own farm, for fodder use or for disposing of dairy effluent.

Getting rid of giant trees

Many old poplar and willow trees have become too big to manage effectively, and this will become an increasing problem as many thousands of trees age. It is vital to determine what to do with these trees and this project will develop robust guidelines on optimum tree management and future planting patterns.

Ian McIvor of HortResearch is working on two Manawatu and Rangitikei farms that have some very large poplar trees and is looking at the best methods for killing these giants. The trees for the trial are growing on steep slopes and range from two to over three metres in circumference at breast height.

Two herbicides, sold as Escort and Roundup, are being evaluated at either varying strengths or volumes to see what kills the trees most effectively. Holes at least 7 mm in diameter are drilled at a downward angle through the bark and at least 30 mm into the tree. The herbicides are then injected into these holes using a hypodermic syringe, though a farmer could use an old drench gun.

The holes are spaced 10 cm apart around each tree at around waist height and two millilitres of chemical are injected into each hole. Escort was applied at three concentrations ? half, one and two times the recommended rate. Roundup was used undiluted so the hole spacing was varied – either 20 cm, 10 cm or 5 cm apart.

The treatments were applied last spring and continued until April to identify the most effective poisoning time and what dose is satisfactory, either for effectiveness or economy. The results will be published in the poplar-willow project’s twice-yearly newsletter PWNews, available from project manager Dr Grant Douglas of AgResearch.

Pollarding poplars in Otago

Otago consultant Dr Barrie Wills has monitored a poplar forage trial at John Prebble’s Dunback farm, near Palmerston in coastal Otago. John has pollarded poplar trees for drought fodder since the 1980s and is keen to see the concept developed and refined. Pollarding treatments on Flevo poplars started in November 2004 when re-growth was trimmed, leaving branches either around 20 mm in diameter or branches less than 20 mm diameter. Some trees were left untrimmed.

It appears that trimming pollarded poplars to leave branches less than 20 mm in diameter will enable a farmer to harvest more and slightly heavier branches than leaving thicker branches when pruning. The untrimmed trees show just how these poplars can grow, and gain branch weight, within a year. Unless they are trimmed regularly they can develop dangerous heavy branches.

But the big question with these trees remains – does a farmer keep the trees growing for a significant drought, or should the trees be trimmed at regular intervals anyway, to keep them leafy and bushy? John Prebble is now considering a rotational block-cutting regime to prevent accumulation of heavy branches. It would ensure sufficient mature trees were always available, and spread the labour for tree maintenance.

Absorbing effluent

Effluent management is an increasing issue on intensive dairy farms, and one possible option for these farmers is to spray irrigate their dairy effluent on to special purpose blocks of trees that take up nutrients. So another Otago trial is looking at the possibility of using willows for absorbing dairy shed effluent. The work is based at Wharetoa, by the Clutha River just northwest of Balclutha, on a dairy farm owned by brothers Dick and Tim Sharpin, where a block of willows was planted for the purpose in 2003. Effluent is being sprayed among the growing trees, using a K-line irrigation system. The willow yield and survival has been assessed in late summer during the past two years.

It is intended that the trees will be coppiced? cut to ground level? regularly and the material fed to cattle. The Sharpins do not intend to use the feed for their cows, but will use their young stock to eat the willows. Water quality around the site is being monitored by Bruce Monaghan of Otago Regional Council to ensure environmental requirements are maintained. So far the water quality in the nearby Washpool stream is impressive, and the stream is clear and very much alive.

While this work is only at the experimental stage, the concept is one that could well become important as the need for pollution control on dairy farms increases.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand