The farm forestry model: Peering into both silos

Denis Hocking, New Zealand Tree Grower February 2008.

This article was originally aimed at a pastoral farming audience, therefore its evangelical fervour. However as the NZFFA is keen to promote the Farm Forestry Model, it is reprinted here as a summary of some of the key arguments supporting the integration of forestry into the land use mix

Forestry, and in particular plantation forestry, is a significant land use in New Zealand with plantations covering approximately 1.8 million hectares of New Zealand's land area. However, as people in the Taupo and South Waikato area are only too well aware, that area is now shrinking for the first time in history. Plantations are also a significant land use on New Zealand farms but no reliable statistics exist for the areas involved.

Integrating plantation forestry

Farm forestry, which we will define as the integration of plantation forestry, or in a few cases, indigenous forestry, into a farming operation, has a long history and certainly pre-dates the establishment of the NZ Farm Forestry Association in 1955. However, it has never been widely accepted by mainstream farming interests. Therefore, although the old NZ Forest Service, and subsequently the Ministry of Forestry, as well as the Catchment Boards to a lesser extent, championed farm forestry, the Department of Agriculture and the original MAP, Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, showed little if any interest and in some cases apparent hostility.

|

|

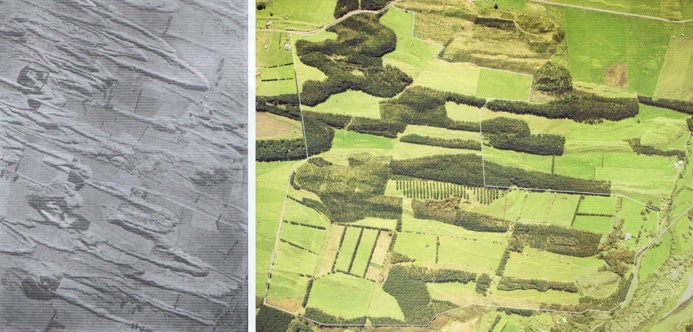

| Aerial photograph 1949 of local sand country showing land forms | Aerial photograph 2003 of Rangitoto showing what farm foresters can do to sand country |

Considering the importance of their extension services through into the late 1980s, attitudes in MAF were influential in guiding land use policies in New Zealand and constraining farm forestry plantings. In turn, attitudes in MAF probably reflected attitudes in the universities, where we saw little interest in, and no courses available for farm forestry till the 1980s, around 30 years after the establishment of the NZFFA. It has, for the most part, remained a minority interest and recently Lincoln University has reduced its forestry offering. I host the Massey University 'Trees on Farms' students each year and have seen numbers move from a dozen or so in the 1980s to a peak of around 50 for a couple of years during the planting boom of the mid 1990s back to 12 to 15 since 2000. Not all these students are doing agricultural degrees. Forestry training is, of course, kept well clear of agriculture and other land uses in the School of Forestry at Canterbury University.

Support for farm forestry

There have been other indicators of mainstream agriculture's discomfort with forestry, notably at local government level and culminating perhaps in the Wairoa appeal of 1977, which severely restricted farm forestry in the Wairoa County but ironically, may well have opened the way to Roger Dickie's investment forestry purchases in the area 20 years later. Attitudes probably derived from earlier generations who saw trees as the enemy and worked so hard to clear the bush to make way for pasture. As outlined above, farmers have not been exposed to forestry in their education and training.

However there have also been some interesting examples of support for farm forestry. A 1963, Massey, MAg Science thesis looking at land use in Manawatu coastal sand country concluded that 'dairy farming combined with farm forestry (on the different soil types) was more profitable than either enterprise on its own'.

This may all seem ancient history, but bear in mind that forestry is a long term land use strategy and it is the plantings of the late 1970s, planned perhaps in the mid-1970s, that are being harvested today. In addition, the development of any farm forestry operation tends to be an extended operation, involving steady planting of appropriate land over a generation or more.

No extension service

Today's Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry has no extension service and no official advocacy role. Amongst the numerous private sector and industry farm and forestry consultancy services there seem to be very few, if any, that handle the various farming and forestry land uses in an holistic fashion.

There was renewed interest in forestry in the wake of the 1993 log price spike and high levels of planting followed. A significant part of this new planting was on farms, but it can also be argued that this planting boom did not result in optimal land use decisions with little of the land that needed forest cover actually being planted and significant areas of class V land or better being planted.

Over the last five years, new plantings have dropped to close to zero and deforestation has become the norm. While this might be blamed on declining log prices, the Green Solution Calculator, a computer programme designed to compare forestry and pastoral farming returns, indicates that on land carrying less than five stock units per hectare, radiata pine is generally more profitable at six to seven per cent discount rates. In addition, returns for Douglas fir and, in particular, good quality cypress logs, have been very good.

Forestry advantages

So, what are the advantages and disadvantages of forestry compared to pastoral farming. Many of the advantages of forestry are environmental in nature, though major economic consequences flow on from a number of these effects.

Forestry offers the following environmental advantages over pastoral farming —

- Reduced soil erosion

- Improved water quality in streams and water bodies, with reductions in nutrients, sediments, faecal coliforms and water temperatures, though with the risk in some situations of reduced flows

- Carbon sequestration

- Increased indigenous biodiversity

- Improved animal welfare with shade and shelter

- Amenity gains, though this is inevitably subjective

In addition, it should be recognised that forestry is not generally competing with pastoral farming on the more fertile, productive pastoral land. As the Green Solution Calculator confirms, forestry is generally better suited to lower productivity, class 6 and 7 land. The farm foresters' experience has been that on hill country properties, considerable areas can be afforested before stock numbers need to be reduced. This reflects the fact that —

- The sensible approach is to start planting the low productivity, often erosion-prone land.

- Significant grazing is normally available in plantations from year two to three through to about 12 years.

- Inputs such as fertiliser, weed control, even time spent mustering, can be saved and invested in higher performing parts of the farm.

- Planting awkward gorges and gullies may well reduce stock losses.

Another advantage of forestry is that the harvest is a flexible feast and can be advanced or delayed several years, or in the case of cypresses, several decades, depending on markets and financial requirements. If the landowner, or more likely family, can do the work, a well planned afforestation programme can be undertaken with comparatively few dollars spent.

A sizable asset, such as a well managed plantation, can be a great asset to aid inter-generational property transfers — paying off the siblings or retiring the aged parents.

On the other hand there are disadvantages to forestry:

- It is a long term investment, with significant early investment, typically $3,000 to $4,000 a hectare, perhaps higher for alternative species, and little prospect of returns before 10 years, and a full rotation of close to 30 years for radiata pine. Cypress offer greater flexibility than radiata pine and can be harvested at younger and older ages.

- The time factor increases the risk of losses from wind throw, disease or fire, probably in that order.

- Forestry is an illiquid asset, with the tax system penalising any sale of a partly grown plantation, even if a market existed. At present the expectation is that the same individual or family should plant and harvest any plantation, while lambs and cattle can change hands several times in a few months or years.

- The real estate market does not appear to recognise the value of plantations on a property.

- Most farmers are unfamiliar with forestry processes, including harvesting and marketing, often seem reluctant to seek out advice and horror stories are quite common.

Is it profitable?

So is farm forestry profitable? In my own case, Rangitoto Farm, the property is on Foxton phase, coastal sand country close to Bulls. Approximately 45 percent of the property, basically the sand dunes and limited areas of drier sand flat, is forested. Approximately 70 per cent of the plantation area is in radiata pine, five percent cypress, four percent blackwood, and 20 percent various eucalypts, mainly E. muelleriana, E. pilularis and related stringybark eucalypts.

The dunes are a fragile land form at risk of wind erosion, summer dry, relatively infertile and with limited stock carrying capacity, typically three to five stock units per hectare. By contrast, the soils on the flats are more fertile with variable moisture status and stock carrying capacities of 12-20 stock units per hectare.

One of the unusual features of the sand country is the lack of natural run-off. There are few, if any streams, rather an unstable water table that can fluctuate some metres through a season. Combined with the highly anoxic nature of the iron-saturated ground water, this can make the flats a rather hostile environment for trees.

Forestry history

The first plantings were of radiata pine in the late 19th century, with a small macrocarpa plantation planted around 1930. When the family bought the property in 1955, there were about 15 hectares of untended plantations. These were harvested in the 1960s and replanted so that when I took over in 1975 there were approximately 30 hectares of generally well tended plantations, mainly radiata pine, but also some cypresses, eucalypts and arboretum plantings.

Log sales have been a significant part of gross farm income since the late 1970s, with production thinning initially, and annual clear felling harvests starting in 1990.

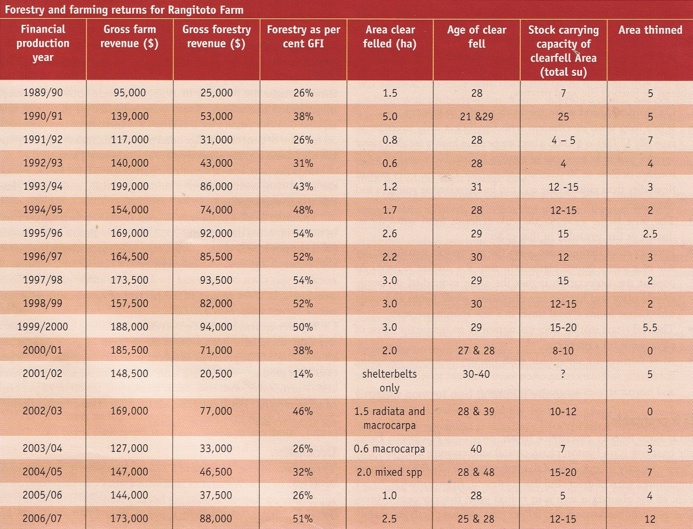

The contribution of forestry to gross farm income is summarised in the table. Note that up until 2002, sales were almost solely radiata pine, but since 2003 other species, especially macrocarpa, have been sold either as logs or sawn timber. In 2005 a considerable volume of eucalypt was sawn on farm and used for new cattle yards and farm structures. In 2004 an area of 0.6 hectare of macrocarpa returned, net of harvest costs, over $30,000

Forestry returns listed are gross returns including harvesting costs. Typically these have been around 20 per cent of gross returns for clear felling radiata pine, but in recent years have approached 30 per cent. For production thinning with contract crews, costs are higher and returns lower, with costs often accounting for 80 to 90 per cent of gross returns. For most years, clearfell harvesting has accounted for 70 to 80 per cent of gross returns.

Conclusion

Throughout the 1990s a total of 500 stock unit years of forestry made up of two to three hectares of land with a stock carrying capacity of approximately five stock units per hectare committed to forestry for 30 years, matched returns from approximately 2,000 stock units for one year. Currently it would take closer to 1,000 stock unit years of radiata pine to match 2,000 stock units of sheep and beef. Cypress would still be close to 500 stock unit years. Farm forestry is still a valuable, commercial land use, even before the environmental gains are considered.

Some farm statistics

- Area 247 hectares - approximately 130 hectares in pasture, 112 hectares in plantations.

- The family purchased 160 hectres in 1955 with a further 87 hectres added in 1989.

- Soils Foxton black sands approximately 40 per cent, Awahou/Himitanga sands on drier flats approximately 40 per cent, Canarvon sands perched water table approximately seven per cent, Pukepuke brown sands fertile flats four to five per cent, Ohakea silt/loams eight per cent.

- Livestock 100 breeding cows, dairy cross to Simmental terminal sire, 750 to 800 Coopworth ewes half to terminal sire and half to Coopworth and 200 to 250 ewe hoggets. Breeding operation only with sale of early store lambs and weaner calves.

- Climate average rainfall approximately 900 mm, high wind run and normally summer dry. Significant frosting on the flats with some bad frost hollows.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand