The battle to hold the hills

Denis Hocking, New Zealand Tree Grower February 2006.

Erosion is an inevitable feature of the New Zealand landscape. Well it certainly has been over the last 20 million years or so when New Zealand has been pushed up and buckled around by tectonic forces. Rapidly rising land forms, large areas of soft rocks derived from marine sediment and periodic intense rainfall are a recipe for erosion. Of course, you can also add earthquakes and volcanic eruptions to the mix. This is geology on amphetamines.

A natural phenomenon

If erosion is a natural phenomenon for New Zealand, the present rate of erosion in our softer sedimentary hill country soils is not natural. In the 80 to 150 years since much of our hill country was converted from forest to pasture cover, rates of soil loss have increased about ten fold, especially from surface slipping, gully erosion and earth flows. The results are numerous and often spectacular.

- Rapid thinning of the depth of topsoil from perhaps a metre under indigenous forest to 10 to 20 cm or less under pasture. This means a loss of nutrients which can, and generally have been, replaced ‘out of the bag’. But inevitably there is also an irreplaceable loss of moisture holding capacity and a sustained decline in pasture productivity on old slip scars.

- Damage from slipping to farm and public infrastructure such as fences, tracks, roads and culverts.

- Increased sediment loads in many of our rivers, with a loss of channel capacity, often a raising of river beds, extra silting on flood plains and a huge dump of soft sediment out on to the near shore sea beds.

- There is also a significant loss of sequestered soil carbon, significant amounts of which will be converted to the greenhouse gas methane from fermentation in anaerobic sediments.

Serious environmental problem

Soil erosion has to be one of New Zealand’s most serious environmental problems and has been for many years. It is over 80 years since Guthrie Smith wrote about the problems of deforestation and soil erosion in his classic Tutira. Catchment Boards were established in the 1940s and 1950s, prompted in large part by the 1938 Esk flood and we did see some response to cyclone Bola in the form of the 1992 East Coast Forestry Project.

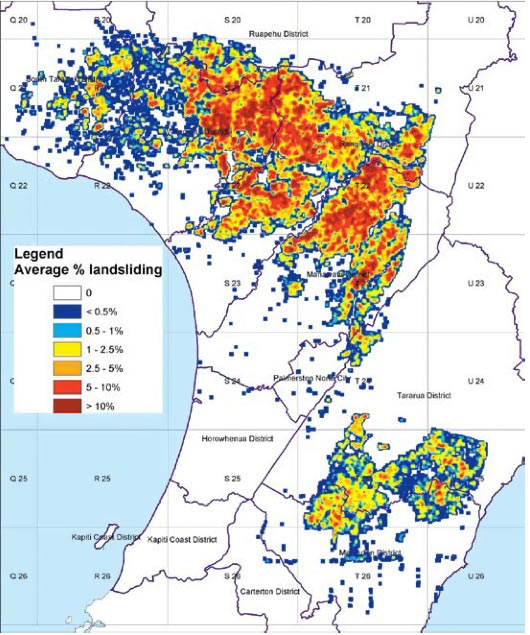

There have also been numerous studies on the impacts of different floods and storms, including the 1977 Wairarapa storms, cyclone Bola, and the 1992 winter and 2004 flood in Manawatu and Wanganui.

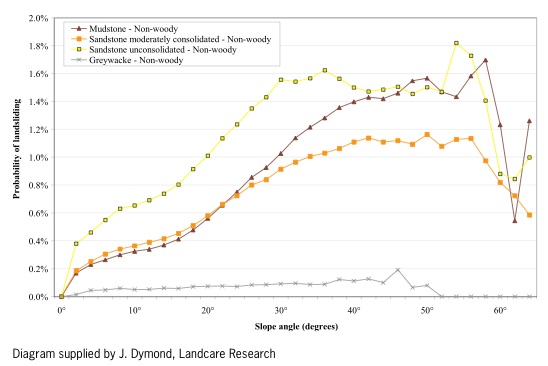

All these studies came to the same conclusion – closed canopy forest cover, be it indigenous, exotic plantation or even taller scrub cover, reduces soil erosion on unstable slopes by around 90% compared to pasture cover. The 1992 study also looked at the efficacy of spaced poplars and concluded that well maintained, spaced poplars reduced soil erosion by about 60% to 70%, while poorly maintained poplar plantings had minimal effect. In other words, there is still three or four times as much erosion under good spaced, poplar plantings than under closed canopy forest.

Yet for all this experience and research, it is difficult to avoid the feeling that over the last 10 to 15 years, soil conservation has dropped below the political radar and off the national consciousness. Central government has washed its hands of the business and it has been relegated to the recesses of the regional councils.

How trees reduce soil loss

Landcare Research scientist Mike Marden seemed to come to rather similar conclusions in an excellent paper in the November 2004 NZ Journal of Forestry. Anyone interested in the issues of soil erosion and land use should read this paper, which is one of the best reviews of the subject that I have seen.

As Mike Marden’s paper emphasises, we know a lot about the processes of soil erosion and how trees and forests act to reduce soil loss. There are several mechanisms. The canopy reduces the damage that is done directly from falling rain by interception and significant re-evaporation, transpiration reduces excess moisture in the soil, but the key effect is the mechanical reinforcement of the soil provided by tree roots. The article by Leith Knowles explains this effect and the requirement for about 30 tonnes of radiata pine root mass per hectare to ensure effective protection. Poplar and Douglas fir have less root mass but higher tensile strength, resulting in similar levels of protection per tree.

There is more debate about whether forest cover reduces the speed and scale of flooding during major storms. It probably does, but according to a recent FAO report, the effect is relatively minor compared to the role of forest cover in stabilising soil cover. However, local anecdotal information suggests that this effect can be quite significant.

Why so much erosion prone hills?

Why so much erosion prone hills?

If we know about the problem and understand the solution, why do we still have millions of hectares – variously estimated at two to five million hectares – of erosion prone hill country in pasture rather than forest? We can only conclude that despite the talk of clean, green and sustainable, many hill country landowners are quite happy to settle for brown, scoured and a quick buck. A Kyoto related meeting in Wanganui in September gave a rather disconcerting insight into the thinking of a group of high profile hill country farmers – dedicated to eradicating scrub, singing the praises of subsidies to this end especially the old Land Development Encouragement Loans of the 1980s, and overwhelmingly opposed to plantation forestry. But, as noted above, we have also had changes in local and central government over the last 20 years that have shifted the focus. With regional councils succeeding and subsuming the old Catchment Boards in 1989, and being delegated many other resource and environment related functions, soil conservation seems to have taken a distant back seat in most cases. Meanwhile central government, which had played key roles in soil and water issues through the Ministry of Works and the National Water and Soil Conservation Authority, dispensed with these institutions in 1988, washed their hands of soil and water issues and devolved all responsibilities to regional councils.

Today I think it is fair to say that there is renewed interest in soil and water issues in Wellington, but it is not clear where any responsibilities fits. And have you noticed how old most soil conservators seem to be these days?

Lessons learned from the field day

What are the lessons we took away from the field day described below (see NZ tree grower, February 2006 pg 20)? I fear that the first, and perhaps most significant, was the complete lack of interest by surrounding landowners. It would appear that most of our hill country farmers are just not interested in trees and sustainability and we do not have the institutions in place to educate, enthuse or enforce farmers over land use issues. Various farm forestry branches may do their best, but we desperately need a vigorous, well funded education, extension, technology transfer programme from regional councils and central government. I think the monitor farm programme in particular needs to put a lot more emphasis on land use and sustainability issues.

The second point is that on the Frecklington property, virtually all the plantations were on comparatively low productivity, pastoral country. And if it is not low productivity now, it will be after the next slip. Nor are the plantation areas devoid of grass. This property illustrates very well the common finding that afforestation of the most erosion prone areas does not result in dramatic losses of stock carrying capacity. However I should add that in my experience, sheep tend to find shaded plantation pasture unpalatable, and it is generally better used for out of season cow maintenance. Further to this point we are not talking blanket afforestation in any but a few extreme cases. The Landcare Research group explained that their work on the East Coast typically gave a 50% reduction in soil loss with 20% forest cover in a number of problematic catchments.

Pastoral farming and forestry can co-exist to mutual advantage, something we farm foresters have never doubted.

The need is for trees, not necessarily radiata pine. Blackwood, cypress and eucalypts were all doing a very effective job at Rewa and there are other options such as fodder trees that might be worth exploring. Spaced poplars have their place on lower erosion risk country, but are definitely much less effective than closed canopy forest. One of the lessons learnt from the 2004 storm was the need for more fastigate form poplars, tall and skinny like the old Lombardy poplars with less sail area and shading. Several new clones that are in the system fit this bill.

Loss of institutional knowledge

Perhaps one of the most worrying features with this whole problem is the loss of institutional knowledge and experience within the remaining institutions dealing with soil conservation. As outlined above, central government washed its hands of soil and water issues almost 20 years ago and the obvious repository for such issues and expertise, the Ministry for the Environment, has neither the funding nor staff to handle it. In addition, some regional councils seem to have lost, or even actively dispensed with, soil and water expertise.

It is not too late to rescue much of this expertise, but we must move quickly. We also need to move very quickly to entice capable, new entrants into the field, train them and then offer them attractive career paths. Soil conservators, or whatever name you want to burden them with, need to have a status beside, or preferably above, farm consultants.

Funding and subsidies

Funding is another issue we have to tackle. Who pays, and how much, for soil conservation services from plantations or reversion to indigenous forest? In National Water and Soil Conservation Authority and Catchment Board days significant subsidy funding flowed through from central government to Catchment Boards and from there to landowners with Catchment Board schemes. But many of these were wasteful – Rolls Royce standard schemes where only a Suzuki standard was required – and economically inefficient. Inevitably, direct subsidy schemes tend to reward mediocrity and devalue the efforts of good operators who do the job themselves. Brian Connell, then National Party spokesman on forestry, made it clear at the Frecklington field day that they had reservations about direct subsidies. Would joint ventures, with government bodies sharing the funding and the proceeds, be more acceptable?

The question of responsibility

Underlying this debate is the question of responsibility for soil. Under the Resource Management Act, soil is in a different category from air and water and in essence belongs to the land owner. But should the land owner have a responsibility to keep this topsoil on the hills and out of the waterways, or are soil conservation plantings a public service justifying tax payer or rate payer funds? It is noteworthy that Horizons is trying to pursue a big, tax payer subsidy approach to soil conservation.

I am undecided about these issues. In a perfect world, landowners take responsibility for their land and act accordingly. In the real world this obviously does not work, or it does not seem to work very often, but I think we should be questioning the extent to which landowners should have their shortcomings covered by tax payers?

The one argument that is unassailable in my opinion is the need to need to bombard these landowners with the technical and educational information on the role of tree cover in soil conservation and the range of possibilities available. It is all old hat to farm foresters and there was once a time when we thought we were world leaders in this area. But how effective has the message and the messenger been in recent years? I still feel the real battle is for the hearts and minds of hill country landowners and there is no doubt in my mind that the whole country needs to join in that battle.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand