Establishing native hardwood trees for timber

NZFFA Information leaflet No. 24 (2005).

There is in New Zealand a constant demand for high quality wood products made from native species, including hardwoods, principally for joinery, furniture and the tourism markets. As greater restriction is placed on extracting timber from the dwindling natural forest estate, the most logical long-term solution is to establish new hardwood plantations managed for, amongst other values, timber production.

A survey of native tree plantations by Forest Research in the mid-1980s (Pardy et al. 1992) identified species that showed promise for growing or managing for timber production in plantations. The two most commonly planted and best performing hardwoods were the predominantly North Island species, puriri (Vitex lucens) and rewarewa (Knightia excelsa). However, other hardwoods with well-regarded timber qualities (visual and working) include kohekohe (Dysoxylum spectabile) and mangeao (Litsea calicaris).

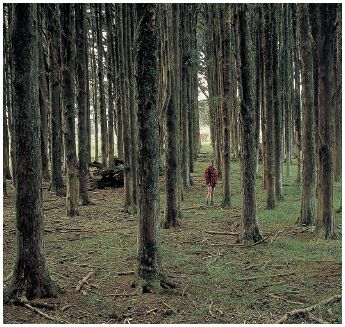

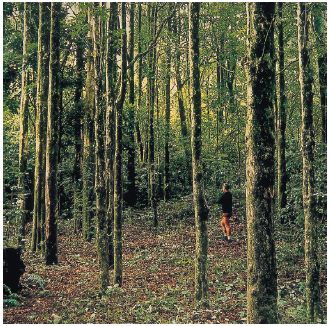

Despite being healthy, having high survival and good growth, stands that were established without a sheltering nurse crop often had little usable timber due to poor form. In contrast, stands growing within or surrounded by a tall cover of vegetation produced straight boles despite the frequent lack of tending.

Therefore a research programme was initiated to investigate methods to improve on what had been observed during the survey.

Sites with existing natural scrub cover

(“If you’ve got it – use it”)

Rather than removing existing high vegetation before planting, where possible and practical such cover should be regarded as a nurse crop and an asset for the development of new plantings. These nurse crops may comprise single or multiple species native cover, frequently manuka (Leptospermum scoparium) and kanuka (Kunzea ericoides), or mixtures with exotic species e.g. gorse (Ulex europaeus). Forest Research has established a number of trials on the East Coast of the North Island where hardwood seedlings have been planted beneath existing vegetation using different methods of establishment including lane and gap planting.

Lane planting: Lanes have been cut in scrub to allow planting of a range of indigenous species and to compare different lane widths and their influence on survival, growth and stem form. Lanes vary between 1 and 6m wide, with widths based on the height and vigour of the surrounding vegetation and the individual requirements of the species being planted. Initially lanes exceeding 3m increase the incidence of frost damage to young seedlings, although over time lane widths narrow as further growth of the scrub occurs. An undisturbed dense canopy suppresses or slows seedling growth and/or results in damage or hindrance to emerging leaders.

Although stocking rates have not been tested thoroughly at this stage, it is unlikely that there is a need to exceed 400 to 500 stems per hectare of the desired hardwood tree species. Lane centres 8m apart and seedling spacing of 3 to 6m will result in stockings of 200 to 400 stems/ha. In one trial using this method of establishment, puriri, titoki (Alectryon excelsus) and rewarewa planted in 3m wide lanes are up to 6m tall after seven years, with predominantly single leaders. Estimates of costs in 1997 to cut 3m wide lanes in scrub with minimal understorey over 1ha of scrubland using 8m lane centres are $500 @ 44c/m.

Gap planting: An alternative to lane planting is to establish parallel access tracks through scrub and at regular intervals cut circular gaps 4 to 6m in diameter within which 3 to 4 seedlings are planted. A planting pattern with access lanes at 10m intervals, gap centres at 15m intervals along lanes and 3 to 4 seedlings per gap equates to a stocking regime of 180 to 240 stems/ha. In a trial in the Auckland Region, puriri planted in gaps in 4 to 6m manuka cover were 2 to 3m tall after 4 years, but did not show as strong a tendency for single leaders as those planted in lanes. Canopy gaps exceeding 6 metres in diameter appear better suited to light-demanding species, but will place frost-tender hardwoods at risk.

Artificial nurse crops

A number of trials have been initiated to establish nurse crops on open pastureland prior to the eventual planting of hardwood timber species. The aim of these trials is to determine appropriate species and planting patterns for nurse crops, and to establish woodlots of hardwood timber species for future research.

After almost 10 years the three most successful nurse crop species are manuka, kanuka and tree lucerne (Chamaecytisus palmensis), although akeake (Dodonaea viscosa) has also shown good potential. Nurse crops were established as single-species blocks, and to date a number of stocking regimes have been tested ranging from 800 to 2500 stems/ha (3.5 x 3.5m – 2 x 2m).

The advantages of higher stocking rates have been better weed suppression and the development of a sheltering cover for the final crop species sooner than for lower stocking regimes. Advantages of lower stocking rates revolve around the cost of establishment as fewer seedlings are required but releasing and weed control costs are higher.

At the highest stocking rates, frost tender hardwood species were planted within 3 years of the establishment of the tree lucerne and 4 years for the manuka/kanuka nurse crops. At the lower stocking rates, the establishment of frost tender hardwoods was delayed until 5 years after planting. For all planted nurse crops canopy closure occurred within 4 years of planting with most species having attained a minimum of 3m in height.

Although not tested in these trials, other species known to be suitable for use as nurse crops, either in mixtures or as pure species cover include the Pittosporum and Coprosma species.

Removing grazing from pastureland and establishing a nurse crop resulted in an immediate up-rush or re-growth of pasture and minor weed species.

While initially this is unsightly, observations suggest that the humus produced by decaying grass and root activity by the new seedlings has resulted in a substantial improvement in soil quality and worm activity 2 to 3 years after planting. By age three most plantings were suppressing grass growth beneath the developing canopy, and birds (native and exotic) were using the sites for nesting. Within 3 to 4 years of planting, viable seed was produced by all nurse crop species, and natural regeneration was seen within but not outside the trial areas.

Beneath these nurse crops, a number of native timber species (hardwoods and conifers) were planted in small single-species blocks.

Experimental stocking rates for hardwoods have been between 250 to 2500 stems/ha although initial stocking rates around 400 stems/ha (e.g. 4 x 6m spacing) will allow for some selection further in the rotation once suitable bole lengths have been formed. The use of the very high stocking rates would assist with form development as young trees emerge from the canopy, but would require substantial future thinning which in these plantings is probably wasteful of expensive seedlings.

Height increments exceeding 1m/yr for individual puriri beneath various canopy types have been recorded in recent trials, while the original survey identified mean annual height increment for puriri and rewarewa of 32 to 49cm for the first 20 years. After four years puriri and rewarewa planted in these new trials average 3.6m and 3.1m in height, with growth exceeding 60cm/year. The majority of these young, emerging trees have single leaders, and are slender and lightly branched.

If this order of height increment is maintained a merchantable bole length of 5 to 7m will be in place by age 10, although merchantable diameters will take considerably longer to be achieved.

A number of reports (e.g. Herbert et al. 1997, Pardy et al. 1992) suggest that, for these faster growing species, diameters exceeding 50cm at breast height will take between 60 and 80 years to achieve, although well-tended plantations on good sites could be expected to improve on these figures. However, it is unknown how much heartwood there would be in comparatively young fast-grown hardwoods at this size. Larger diameter stems (60 to 70cm) may therefore need to be achieved before harvesting to ensure adequate heartwood content.

Recommendations

The early growth and survival of planted native hardwood trees will be improved with attention to the following:

- Control of browsing animals, including fencing to exclude domestic livestock, before any planting;

- Provision of shelter or use of a suitable existing nurse crop;

- Use of high quality nursery-raised seedlings and good planting practices. Seedlings should be tall (preferably 50 to 80cm) especially for sites where competing regrowth is expected. Container-grown seedlings are preferred over bare-rooted seedlings for most hardwood species;

- Good site preparation – pre-plant spraying of grass with herbicides, and where appropriate, cutting lanes or gaps in sheltering vegetation;

- Regular weed control, especially during the first years after planting.

Conclusions

There is now sufficient research to show that native hardwoods timber species can be successfully established where the aim is long-term specialist timber production. Many of these species will grow successfully outside of their natural range with appropriate site selection and establishment practices while their ecology makes them suitable for sustainably managing as either single or mixed species in even or uneven-aged planted stands where future harvesting will involve low-impact selection logging techniques.

Although the management of native hardwoods for timber production will be on longer rotations than exotic conifer species, other values including amenity, landscape and environmental are often important additional objectives incorporated into plans for planting. This may tip the balance for potential growers in favour of planting native hardwood timber species for high value timber production on selected good quality sites.

References:

Herbert, J.W.; Bergin, D.O. and Steward G.A. 1997: Native trees for production forestry. What’s New in Forest Research No. 243. New Zealand Forest Research Institute Limited.

Pardy, G.F.; Bergin, D.O. and Kimberley, M.O. 1992: Survey of Native Tree Plantations. Forest Research Institute Bulletin No. 175.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand