Getting back to basals

NZFFA Information leaflet No. 11 (2005).

There are numerous measures and numbers associated with forestry, some more familiar to farm foresters than others. We hear a fair bit about site index (height at 20 years) that is often used perhaps rather courageously as a proxy for productivity. Likewise, total standing volume and/or recoverable volume are other common measures. While total volume is productivity, it is not necessarily profitability. Along with these height and volume figures we have mean annual increments (MAI), the total volume or whatever divided by age, and current annual increment (CAI), the current year to year increment.

The figure I would like to see acknowledged and used more widely is basal area. In simple terms it is the total cross-sectional area of tree trunks measured in square metres per hectare. To be more precise, it is the under bark crosssectional area at a height of 1.4m, the dbh height. It may not be quite as simple as height and volume but it does tell you about the potential yields of pruned butt logs and so has quite a lot to say about potential profitability.

The basal area (B.A.) and B.A. increment that a plantation can achieve is a variable and depends on numerous factors:

- Age – simple enough, it takes time to grow.

- Stocking rate – to a certain extent. Higher stocking rates will achieve higher B.A.s and B.A. increments earlier, but final B.A.s are less affected.

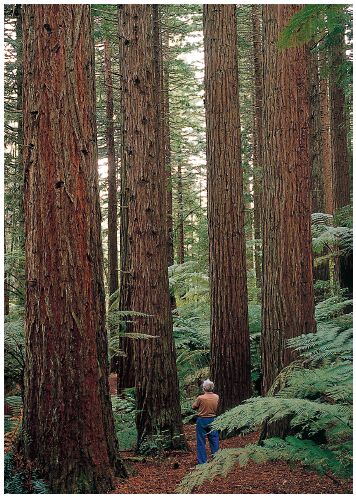

- Species – different species have very different B.A. potential. For example, eucalypts are generally much lower than radiata pine, cypresses are rather higher, and redwoods much higher.

- Fertility – for any individual species, B.A. probably reflects site fertility more directly than any other measure. The more fertile the site, the larger the B.A. and B.A. increment at any specified age and stocking.

- Forest health – tree death seriously undermines the quest for high B.A.s so the lower altitude, higher temperature, drought-stressed or higher humidity and more sheltered sites often lose out on this one.

What is a good B.A.?

Generally, for radiata pine, B.A.s increase quite rapidly to about 45m2/ha, when canopy closure starts to slow the trend. But what sort of final B.A.s should we expect for radiata pine at 25 to 30 years?

I had always been led to believe that they would be in the range 60 to 100m2/ ha, perhaps less on the poorer sites, more on the highest. In fact, the evidence suggest that this is a bit optimistic. At Tikitere, generally regarded as a good site, the 400sph plots had only achieved 70 to 80m2/ha at 25 years, and they would not have touched 100m2/ha till about 40 years, if they could have achieved it at all.

Similarly, a quick flick through the permanent sample plots by Mark Dean could not find any other plots above 70m2/ha at 20 to 25 years, though he did find a redwood plot at 200m2/ha at 90 years. If 70m2/ha is a good B.A. for a farm plantation at 25 to 30 years, then this tells us a bit about appropriate stocking rates.

At 300sph, a B.A. of 70m2/ha means an average dbh of around 55cm. While some might regard this as adequate in a pruned stand, it probably means a good number of pruned logs with small end diameters (SED) below the 40cm minimum for the premium P1 grade.

Still, mathematics being the just slightly perverse subject that it is, even if the average SED is 40cm, a majority of the volume will be in the bigger, more valuable logs.

In an over-stocked stand, smaller diameter trees overall is one possibility, but often dominant trees will continue to grow while subdominants head off to become (pruned?) huhu tucker.

This seems to be the situation in the 400sph Tikitere stands.

On poorer sites, such as many of the sand dune sites, the message is that limited B.A. capacity will severely limit optimum stocking rates and/or diameters.

There are plenty of low fertility, 40 to 50m2/ha B.A. sites and here you won’t get 60cm diameter trees unless the stocking rate is significantly below 200sph.

Crown: stem ratio

Basal area also lends itself to another common rule of thumb – the crown: stem ratio. This is the ratio between average tree separation and final stem diameter. It is quoted typically, as about 12:1 for radiata pine, and 15 or 16:1 for eucalypts. In fact these correspond to B.A.s of about 55m2/ha and 30 to 35m2/ ha respectively and are probably rather conservative for better sites. For radiata, 10:1 might be better for good sites, out to 12 to 13:1 on poorer sites.

As already discussed, B.A.s are good indicators of potential yields of pruned butt logs, but other factors do help, including a high site index. Taller trees will have less taper along with better top logs, of course, but B.A. and B.A. increment is the big factor in yield of pruned logs. With a B.A. increment of 2m2/ha/year (quite feasible, and indeed routine) and a high yield of P1 logs, you can be looking at around 12m3/ha/year of top grade wood. At present net values of around $130/m3, this is approximately $1500/ha/year net value increment for the pruned component alone. It compares pretty well with most other land uses I know of. Blessed be the basal area.

This article and photograph by Denis Hocking appeared in the February 2000 issue of the New Zealand Tree Grower.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand