This is free.

Substituting imported wood with New Zealand timber

Karen Bayne, Jonathan Harrington and Harriet Palmer, New Zealand Tree Grower February 2024.

Small-scale forest owners are the main growers of specialty timber species. Growers have invested in planting stock and silviculture with higher costs than radiata pine in the expectation that high-value markets would emerge for them to obtain commensurate rewards.These high-value markets remain elusive to many.

If you visit a large store you will find imported timber and timber products galore, but few locally grown options. New house builds and renovations feature attractive timber joinery and floors, almost always all imported. Growers are justified in thinking that New Zealand timbers could substitute for some of these imports. But how can our alternative species penetrate markets currently supplied by timber from overseas?

The Scion team investigated how the value chain operates, from international suppliers through importers, to the architects, designers and builders who specify the products in building projects.They assessed opportunities for displacement of imported timbers by locally grown and manufactured wood products, with a focus on durable exterior products such as decking and cladding, interior fitout, furniture as well as other miscellaneous wooden items.

Main research questions

Three key questions in the study were –

- What is the current specialty timber resource base in New Zealand?

- What timber species are being imported and why?

- How are architects and designers selecting timbers for projects?

The researchers reviewed the available data on the current New Zealand trees growing and being harvested, and the sources, volumes and values of different species and products being imported.They also undertook a series of interviews.They talked to importers, architects and designers as well as New Zealand growers and processors of alternative species.They visited people and businesses considered to be examples, and finally held an on-line workshop to discuss the most promising opportunities for gradually introducing New Zealand grown timber into the markets identified.

The current market for specialty timbers

The current import mix involves over 30 countries including more than 50 species and products. Of these, 28 main species were identified with around 20 countries supplying most imports. China is by far the largest supplier of imports. In 2022 China supplied over 70 million tonnes of mainly manufactured goods, followed by Indonesia with around 32 million tonnes, then Australia, the USA, Canada, Chile and Germany.

Eight of New Zealand’s larger timber importers provided information about the species mix they import. Not all importers bring in the same species, but almost all importers stock kwila, purpleheart and vitex. Most stock western red cedar and oak, either American white oak or European oak, as well as various hardwoods.

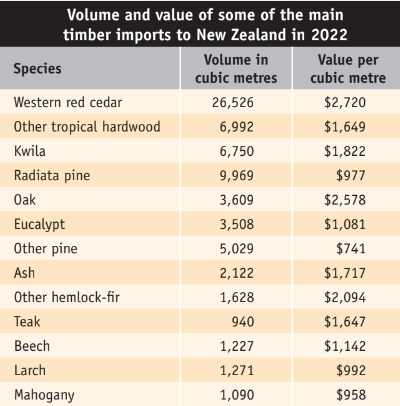

The table below left shows the quantities and value of the main imports by species.Western red cedar used mainly for cladding is by far the predominant import by volume. Highest prices per cubic metre are paid for kwila, western red cedar, oak and walnut, although very little walnut is imported.There is a big range in value, from almost $3,000 a cubic metre to less than $500 a cubic metre. Almost 10,000 cubic metres of radiata pine were imported at an average value of $977 a cubic metre. Some trends include consistent growth in the volume of western red cedar imported and recent rapid growth in imports of modified timber.

What importers want

Importers are very clear why they are importing a particular species. Consistency in appearance and grade, good durability, fit for purpose for all New Zealand’s climatic variation, cost and constant availability are very important.The bulk of imported timbers are tried and true species, introduced a long time ago and popular in the New Zealand market such as kwila for decking or western red cedar cladding. Others are species which are known to perform well for a specific purpose internationally, such as American ash furniture, oak flooring and certain boat building timbers.

The five big merchant stores – Placemakers, ITM, Bunnings, Mitre 10 and Carters – are the main customers of importers.These retailers and their customers dictate what is brought into New Zealand in terms of veneered panels and sawn timber, especially for exterior use. Furniture and manufactured goods retailers are other important customers.

Almost all imports are certified as either FSC or PEFC.This certification is an indication that the timber is sustainably sourced and is now vital for importers and their customers. It is something which New Zealand specialty timber growers will have to sort out. Importers know what grades of timber they want and expect confirmation of grade and product consistency before the timber is shipped to New Zealand.

What architects and designers want

Architects and designers emphasised that product appearance is all important. Most projects do not have a species in mind, it is their design aesthetic which matters. Choice of timber is then based on previous experience with a timber and a supplier, along with the requirements of the client.

The product specification process by architects includes looking at their own materials library, experience from past projects and reviewing recent award-winning projects. Júnior staff rely on senior architects and knowledge of past projects to help select species and supplier.

Architects will specify timber, and then the project manager, architect and shopfitter or builder will consult to determine what species could be used, with additional advice coming from suppliers. At times there is just a brief on colour sought and what it will be used for, size or thickness. A timber yard or stockist will make a species recommendation, send samples or a sales representative will visit to finalise the selection.

What matters when selecting timber

The list below, in order of merit, is what matters to architects when timber is selected.

- Supply availability

- Sustainability

- Project cost

- Dimensional stability

- Fire resistance

- Price

- Colour or tone

- Environmental certification

- Finish

- Imported versus local product

- Available sizes

- Carbon offsetting

- Presence or absence of knot

- Impact resistance

- Fine or coarse grain

- Uniform grain direction

- Flex and ability to wrap or curve

- Moisture resistance

- Weight

- Easy to machine

- Importation requirement

The ranking shows that whether timber is imported or New Zealand-grown is relatively unimportant, but more important than some of the more detailed timber properties. Predictable lead time and availability are crucial.Timber must arrive on site when needed and be of the grade specified so that builders can get to work without delay or needing to experiment on site.

Most architects did not know who to contact or how to obtain information about New Zealand grown non- native timber.Where a known supplier was mentioned, it was generally through already established supply chain importers and timber merchants who offer New Zealand grown timber alongside imported sawn timber and veneers.

Identifying substitution opportunities

Several possible import substitution opportunities were presented for discussion to the participants in on-line workshop.These included –

- A replacement for imported hardwood decking such as kwila and garapa – could a local hardwood such as Eucalyptus saligna substitute for these imported timbers?

- Exposed exterior joinery and cladding – could locally grown timber, perhaps thermally modified, be used to replace western red cedar?

- Thermally modified hardwood cladding – could this be replaced with thermally modified poplar?

- Others including boat-building ply, outdoor furniture, prefabricated buildings such as sheds and cabins, and indoor furniture.

Workshop participants looked in detail at the decking and thermal modification opportunities to discover the practicalities of what would be needed for a realistic attempt to substitute imported timbers for the target market segment.

The way forward

One conclusion from the study was that a dedicated, professional sales agency or industry association could be the best way to take New Zealand-grown alternative species timber to market.To date the only option open to growers has been to attempt to market their specialty timber individually – whether before or after harvest – and as a result no supply chain has ever developed. For a dedicated sales agency to be successful, four points have been identified where further work would need to be carried out.

Better knowledge of the growing resource

Remote-sensing technology can be used to develop a nationwide GIS-based mapping system which can accurately identify specialty species in woodlots and forests and estimate age.This will enable better prediction of potential regional wood flows.Work is already underway at the University of Canterbury School of Forestry in this area, but with some way to go.

A process to meet market requirements

A process for consolidating timber to meet market requirements, linked to knowledge of the area or volume of a species needed within a certain geographical radius to service a market.This might include consolidating different species in the way that ash and oak imports are marketed – the product must simply look right and be fit for purpose.Thermal modification technology is also changing the game, broadening the opportunities for some species to fit into previously unavailable market segments.The other issue that arises here is the need to develop multiple product streams from any given species or processing activity, so that as much of the harvested timber as possible is converted into useable products.

Finding ways into existing markets

New Zealand growers just want, and can only currently service, a small slice of the total pie. Imported timber is good and will always be there. For some time to come New Zealand supplies will be limited.The challenge is for a sales agency to link into existing networks that supply the market and present a sustainable supply of New Zealand grown products alongside imported ones. A boom and bust supply cycle needs to be avoided.

A grading system for specialty timber

This needs to be designed to accommodate the grade classifications demanded by the market. A new system may be needed, rather than trying to adapt to radiata pine grading systems.This could be eventually linked to the species-based GIS developed in and capable of predicting timber grades from standing crops.

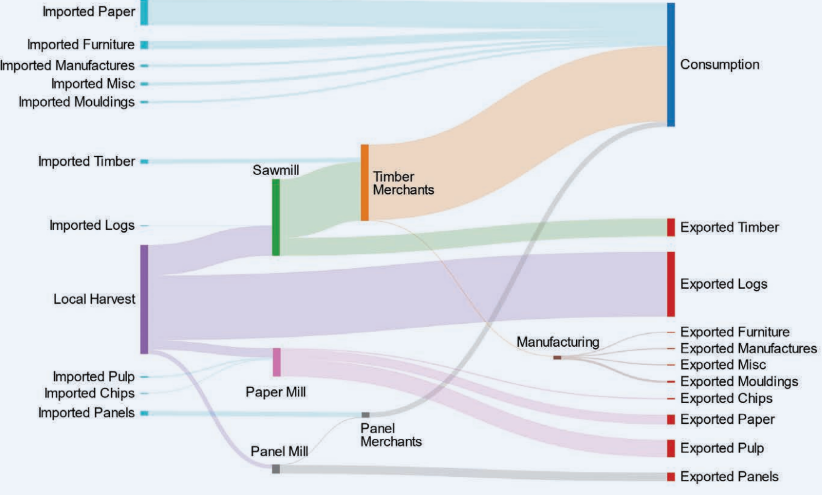

Supply chain problems

The supply chain for timber and timber products is complex. Generally, buyers do not want to know about this, they just want products when they want them.

What is clear is that for New Zealand wood and wood products to penetrate supply chains, buyers need clearer routes to obtain information on –

- Product availability

- Lead times from ordering

- Price range

- Where to get the timber

- Whether samples are available

- Range of finishes

- Compatibility with coatings and treatments

- Dimensions and grades available

- Durability class and use specifications

- Certification status.

Possible solutions

The study team concluded that the most likely way to succeed in penetrating existing markets would be to specifically target some of the low-hanging fruit.This could be by, for example –

Picking a few species which can cover a range of applications and that are ready for substitution and to focus effort on these

Transitioning through imported plantation species, then switch to New Zealand plantation resources once the volume from New Zealand is there Using improved lower grade material. Existing producers of thermally treated radiata pine could undertake thermal treatment of local timber that are poorer quality, such as eucalypts, poplar, acacia or redwood to substitute for imports.

One possible option identified would be to focus on the regional supply of E. saligna and then other eucalypts in Northland, and look to supplying a small segment of the Auckland decking market.The idea would be to ramp up supplies in a planned way, being careful to keep demand matching supplies rather than disappoint the market. At the same time, local growers could be encouraged to plant other eucalypt species suitable for decking such as E. microcorys and E. fastigata to develop a sustainable supply chain.

Further challenges to overcome

The study highlighted several further challenges to be overcome. One is the question why anyone should buy New Zealand grown timber.What rationale could a sales agency use as a marketing platform for locally grown specialty timbers? What makes them better than tried and true imports?

There is an imported species and product for every potential application, and if something happens to limit supply of one species, another is found to substitute for it. Every domestic need for specialty timber can be supplied from overseas.

Historic arguments around New Zealand-grown timbers being environmentally or economically advantageous no longer wash – imported products are FSC-certified and may well be price-competitive with locally grown products. In addition. where homeowners and specifiers are looking to use alternative durable species for outdoor use, unless these had been verified and listed as an acceptable species within the building code NZS3602, local authorities will query the species suitability for application.The risk of such queries will deter specifiers from using alternative local resources over tried and proven imports.

A sales agency would have to find other ways to encourage use of home grown timber.These could include resilience in the face of international supply chain fragility, climate change induced climatic or pest and disease threats, and the lower carbon footprint associated with locally grown products versus imports from around the globe.

Another hurdle is that of small growers obtaining environmental certification for their timber.This needs to be urgently addressed, remembering that certification is essential for the big store buyers. A new independent verification scheme or New Zealand wood mark may need to be developed which will meet the requirements of the New Zealand Green Building Council.

New Zealand specialty timber processors need to be profitable enough to be able to pay growers a fair price, otherwise supplies will not be sustainable. Processing and production costs are higher in New Zealand, so technology could help reduce these costs, ensure customer satisfaction and ease problems associated with finding appropriately skilled labour. However, new technology is never cheap.

The current study did not consider the practical and economic feasibility of getting small volumes of wood from the woodlot to the market.This is another major supply chain conundrum with no simple solution.

Future research priorities

Some future research priorities identified include understanding how to better integrate the supply chain, in understanding the resource in terms of location, age class and quality as well as designing ways to consolidate individual suppliers’ resource together for efficient processing and marketing. Helping in batch processing development of small portable thermal modification kilns, and determining required grade class and grading machines for specialty New Zealand grown species is also a priority.

This article is a summary of some aspects of the import substitution project and a full report is available on Forest Growers Research website.

The Scion Import Substitution Project team consisted of Karen Bayne, Jonathan Harrington, Colleen Chittenden, Russell McKinley and Rosie Sargent.Toby Stovold supported the project. Harriet Palmer is an independent forestry communications specialist.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand