The outlook for forestry in Taranaki

Warren Parker, New Zealand Tree Grower February 2016.

This article is based on the presentation made by Scion at the Taranaki levy information day. It is about Taranaki but much of the information can be used to consider the value of smallscale forestry in many other parts of New Zealand.

Forestry and wood processing are important to the Taranaki economy. The eight wood processing businesses in the region directly employ 500 people and annually pump $28 million of wages into the economy. When farm forestry and plantation forests of 17,560 hectares, transport and other service support are considered, the effect on jobs in the region is probably three to four fold greater.

Total saw log demand in the Taranaki region is currently 160-170,000 cubic metres a year, comprising approximately 26,000 cubic metres of pruned logs, 89,000 cubic metres of A grade logs and 50,000 cubic metres of other logs. Significantly, there is no local demand for chip logs or sawmill slab chip – this needs to be trucked out of the region for marginal returns or left in the woodlot or forest. I will come back to this later.

Log exports from Port Taranaki peaked at 346,300 cubic metres in 2012 and have fluctuated from 119,000 cubic metres in 2010 through to 231,600 cubic metres in 2014. The port is therefore an important outlet for logs, including the lower grades. However, it is unfortunate, given its proximity for local mills, that containerised export products must be sent out of the region.

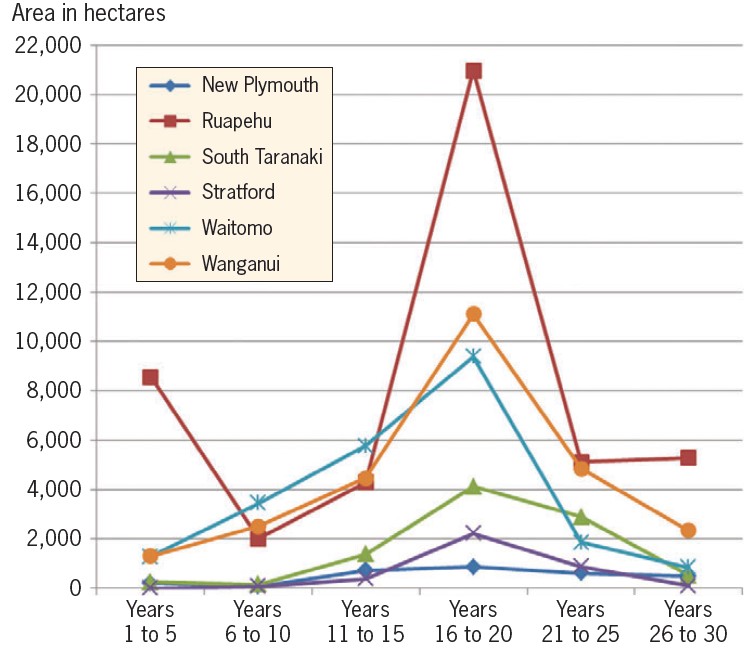

Forecast wood availability in Taranaki through to 2042, shown in the table, illustrates peak regional supply of logs will occur in the mid-2020s and without significant immediate forest plantings a local supply shortfall in a number of log grades will occur by the 2030s. Mills, of course, could procure logs from neighbouring districts such as Waitomo, Whanganui and Ruapehu, but this adds transport costs and some roads are of variable quality.

Strategy shaping forestry

The future for Taranaki forestry is subject to the same problems as the rest of the country −

- Global supply and demand for wood fibre

- Climate change

- Resource scarcity and new environmental limits, especially for fresh water

- Māori land development, given Māori own 40 per cent of the land on which production forests grow and their land and other asset base continues to grow

- The increasing influence of the internet on all aspects of business, including the forest industry supply chain.

Local imperatives also apply including the need to reduce hill country erosion, the development of transport infrastructure and generate synergies with other regional industry sectors such as dairy, poultry, oil and gas.

| Area of forest by five-year age class in hectares | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| District | 1-5 | 6-10 | 11-15 | 16-20 | 21-25 | 26-30 | 31-35 | 36-40 |

| New Plymouth | 211 | 187 | 902 | 1199 | 648 | 491 | 105 | 77 |

| Stratford | 12 | 79 | 409 | 2270 | 920 | 112 | 58 | 10 |

| South Taranaki | 256 | 164 | 1438 | 4158 | 2933 | 520 | 334 | 69 |

| Total | 479 | 430 | 2749 | 7627 | 4501 | 1123 | 497 | 156 |

| Estimated wood availability for each five year period in cubic metres | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| District | 2013 - 2017 | 2018 - 2022 | 2023 - 2027 | 2028 - 2032 | 2033 - 2037 | 2038 - 2042 |

| New Plymouth | 61,754 | 60,632 | 89,207 | 80,011 | 31,367 | 33,907 |

| Stratford | 63,032 | 80,052 | 236,479 | 40,742 | 9,146 | 2,064 |

| South Taranaki | 83,342 | 297,781 | 415,034 | 139,349 | 18,372 | 26,351 |

| Total | 208,128 | 438,465 | 740,720 | 260,102 | 58,885 | 62,322 |

Major transformation

Climate change with the Paris 21 Global Accord in place is of particular significance to the region’s future. To hold the global average temperature increase to below 2o C above pre-industrial levels will, according to the International Energy Agency, require 40 per cent of all new international energy investment from 2030 to be focussed on energy efficient and low carbon technology. In addition, there is an implicit requirement for country contributions to be increased at five yearly intervals because current greenhouse gas reduction pledges will only constrain the temperature increase to an estimated 2.7oC compared to a target of 1.5oC.

Therefore, New Zealand’s current intention to reduce greenhouse gas emission levels to 30 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030, or 11 per cent below 1990, will come under increasing pressure as the rest of the international community also have to shoulder heavier greenhouse gas reduction targets. Increased monitoring, reporting and standardisation of this will add to the transparency and accountability for greenhouse gas emissions reductions for all countries.

The spotlight on accountability will be reinforced by the growing number of businesses who have committed to de-carbonise as well as the already very active non-governmental organisations. With this background in mind, it is obvious that the Taranaki economy, with its heavy reliance on dairy, oil and gas, will undergo a major transformation over the next three decades. It is highly likely that forestry and wood processing, with its environmental and economic benefits, will be an important element in this transformation.

Successful riparian planting

The second major push for environmental limits is typified by the National Framework for Fresh Water Management, which sets new thresholds for water quality and use. It runs in parallel with the Paris 21 agreement as improvements in water quality are inter-dependent with land use. The Taranaki Regional Council’s 2015 State of the Environment Report confirms the region’s fresh water resources and quality are stable compared to many other areas. This reflects proactive steps by the regional council and land owners, such as extensive riparian plantings. Almost 100 per cent of Taranaki’s 1,800 dairy farms now have riparian management plans in place covering about 14,000 kilometres of stream bank.

Nevertheless, the region faces increased weather related risks such as drought, high winds, flooding and erosion due to increased frequency of extreme weather. This is especially important in eastern Taranaki hill country where there are 83,000 hectares of vulnerable land. Trials in this district show that, compared with pasture, tree cover can reduce erosion by 90 per cent and planting open space conservation trees can reduce erosion by 70 per cent.

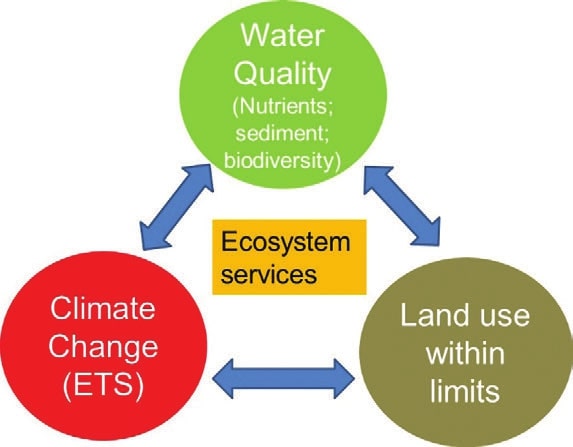

Ecosystem services

The third shaping factor in relation to climate and the environment is the quantification and monetisation of ecosystem services produced by different land use enterprises. These need to be factored into the nett economic benefit derived from them. Externalities generated by dairy and forestry and their associated market and non-market values in New Zealand, as shown in the next table, highlight why this development is important to level the playing field for forestry.

The contribution of forests such as avoided erosion, reduced sedimentation, conservation of indigenous biodiversity, recreation and tourism, are undervalued. This distorts the allocation of capital and imposes costs on the public as is now clearly evident in the central North Island where large scale deforestation has recently taken place.

Importantly, it also shows that the low environmental effects of forestry can be combined logically with more intensive land uses for greater sustainability of land use at the farm and catchment level. However, these positive effects are offset by some of the negative effects of forestry which need to be acknowledged. These include the spread of wildings and pollen, increased sediment entering waterways in the first two to three years after harvesting and the potential for the residues from harvesting to enter waterways during heavy rainfall need to be acknowledged. As with other farming enterprises, best practice management can mitigate the negative and enhance the positive of forestry.

| Externalities and services | Units | Land uses | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dairy | Forestry | ||

| Quantities | |||

| Nitrogen leaching | Kilograms per hectare per year | 15 - 115 | 3 to 28 |

| Phosphorus leaching | Kilograms per hectare per year | 0.30 - 1.70 | 0.01 to 0.10 |

| Carbon emissions | Tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent per year | 8 - 14 | |

| Carbon sequestration | Tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent per year | 35 to 55 | |

| Values | |||

| Carbon | Dollars per tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent | 3 to 9 | |

| Nitrogen | Dollars per kilogram | 350 to 650 | |

| Flood mitigation | Dollars per year | 1 to 41 million | |

| Non-market values | |||

| Biodiversity | Dollars per person | 69 | |

| Recreation | Dollars per visit | 4 to 92 | |

| Land stabilisation | Dollars per hectare per year | 1 | |

| Water sediments | Dollars per hectare per year | 105 | |

| Algae in water | Dollars per hectare per year | 111 | |

| Level of water flow | Dollars per hectare per year | 12 | |

Implications for Taranaki forestry

With the strategic imperatives and local demand requirements in mind it is an opportune time for land owners in Taranaki to reconsider and plan their future investments in forestry. In doing so they should take into account the following –

- To meet future local demand it is clear that planting forestry will need to increase significantly in the next few years. Recent planting rates indicate how small the area is which has been planted in recent years. Land owners have access to the Afforestation Grant Scheme to offset establishment costs and for steeper or higher cost land areas the Permanent Forest Sinks Initiative and possibly regional council support may be available.

- It is surprising how rarely forest owners and farm foresters spend the time to talk to mill operators to get an understanding of their longer term log requirements. As noted earlier, Taranaki has long established frms who are continuing to invest in infrastructure and require security of suitable log supply.

- Forestry needs to be located in areas that provide competitive harvesting and transport costs, around 50 to 100 km from the mill depending on road quality and slope. If this is not the case then options such as the Permanent Forest Sinks Initiative, including planting of manuka, should be considered.

- As with any long term investment the decision to plant is underpinned by confidence in the result. Good advice on forest economics is essential, noting the importance of the Paris 21 agreement and possible changes to the Emissions Trading Scheme on future carbon prices and being able to exploit areas which already have roading and other infrastructure in place for harvesting second or later rotations.

In deciding to plant or not it is essential to −

- Choose the best location and match the species and silviculture to this site. Be aware of high wind risk and take steps to mitigate this in areas selected for planting and the silviculture regime.

- Select the best genetics for the location – investing in high quality genetics provides the foundation for a highly productive forest.

- Generally increase the stocking rate compared to past regimes. There is growing confidence that many sites are under-stocked in radiata pine and for structural purposes a final stocking rate of around 550 a hectare

is likely to be optimal. - Pay close attention to stand management – disease surveillance and control, fertiliser, pruning or not pruning are critical to long term productivity.

Conclusions

The Taranaki region has a proud and long history in forestry and the strategic reasons for forestry and wood products are positive as the world moves progressively to low carbon, renewable sources of energy and materials. Taranaki forests are also among the most productive in the country providing they are established with high quality genetics, well managed and are thinned to an appropriate final stocking rate.

The shortfall in log supply to meet local sawmill demand from the late 2020s to the 2030s indicates that planting should begin now. There are several schemes to support farmers with establishment, and current projections are that the carbon price will continue to increase through to 2030 in conjunction with the climate change abatement initiatives.

Finally, in deciding to venture into or increase forest planting land owners are strongly encouraged to talk to local wood processors regarding their longer term requirements and how they can grow forests to best meet their needs. They can also get excellent advice from the regional council, consultants and of course Scion.

Warren Parker is the Chief Executive Officer of Scion.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand