Another example of the Farm Forestry Model: Glenmore

Neil Cullen, New Zealand Tree Grower May 2008.

The decades of the 1970s and 1980s saw a great transition in landowners’ attitudes towards their farms. Development of the land from tussock, bush or wetland to pasture had been the driving force on many farms as farmers, encouraged by government subsidies, rushed to increase their stock numbers.

Converting indigenous forest to exotic

In our corner of the country, the Catlins in South East Otago, large areas of indigenous forest were cleared during the 1970s by chainsaw, bulldozer and fire. Land in bush was regarded as valueless and the government was actively engaged via the New Zealand Forest Service in converting indigenous forest to exotic forest.

The transition in attitude was part of the world-wide awakening to the concepts that there are limits to the planets resources. The various ecosystems are interlinked, humans have to learn to work with nature and conserve what remains of the unique features, flora and fauna in every region.

First plantings

On our farm in the Glenomaru valley more than 130 hectares of bush had been cleared or damaged by fire during the 1970s and early 1980s. At the same time, with the aid of the Forestry Encouragement Grant Scheme and advisors such as John Edmonds, the first of the forest blocks had been established.

These plantings of radiata pine were on steep south facing slopes of low natural fertility where money spent on fertiliser and fencing was difficult to justify. Much of the remaining native forest had been fenced of from stock. By the time Pam and I took over in 1991 about 45 hectares had been planted in radiata pine.

We continued with the planting of radiata and using seasonal workers from the local meat processing plant, completed the silviculture on the early plantings. In 1996 an adjoining block of 120 hectares was purchased and immediately ten per cent of that area was planted out on a steep south facing slope. As this newly acquired land was exposed to the prevalent south-westerly wind we started to provide shelter using Eucalyptus johnstonii, E.cordata, E. rodwayii and E.niphophila in shelter belts and along with macrocarpa in some of the larger gullies.

Soil types

To assist with better planning of development priorities a soil scientist provided a report on the various soil types on the farm. Being part of the geological feature known as the Southland Syncline, the farm consists of a series of east-west running valleys and ridges. These are overlayed with lowland yellow – brown earths with various degrees of leaching. The most heavily leached and podzolised soil type, Hinahina makes up about half of the total farm area.

The report and soil map helped confirm which areas on the farm were most suited to forestry and where potential for greater grass production existed. Using the model of planting trees on the less fertile soils and less favourable terrain, and at the same time improving the carrying capacity of the better country, allowed us to maintain our stock numbers but increase the forested area to the current 114 hectares. Erosion has not been a big issue except when high rainfall occurs over a short period as it did in February 1991, when 200 mm fell in 24 hours. Sheet erosion from that time is still visible in the district and serves as an indicator where forest cover may be needed.

Fencing off streams

Attendance at a Regional Council field day in the late 1990s on riparian management prompted consideration of how we could better look after the Glenomaru Stream and its tributaries which flow through the property. Starting in 1999 we began fencing of unprotected sections of the stream and planting the banks with a variety of natives.

Although there have been many losses with these plantings they are gradually becoming established and we are told just keeping stock out and having long grass as a filter improves water quality. Provision of alternative water supply for stock is part of this process and we have used ponds and spring-fed troughs, as well as pumping water around the easier country.

On one tributary where unfenced bush adjoined the waterway we obtained assistance with the fencing and in return protected the bush under a QEII covenant. This protection has been applied to other areas of native forest as well and counting three new blocks that are in the pipeline about 100 hectares of the 130 hectares remaining on the farm will be under covenant. There is considerable flexibility in the covenanting process which can include areas of exotic forest and, as we saw at the Wardle’s property recently, on a conference field day also allows for management of native forest.

Harvesting

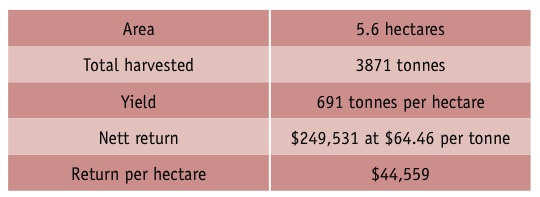

From 1998 we began harvesting small areas of the original radiata plantings and in most cases replanted with alternative species. In 2003 a block of 31-year-old trees was harvested. My parents and brother had retained ownership through a forestry right for these trees. They were fortunate to harvest when prices were at a peak and as can be seen from the table below, returns were very satisfactory. The sale was tendered on nett rate per tonne harvested.

Quite obviously there is no way this area of steep, relatively unfertile land could have produced a nett return averaging $1,437 per year by any other means. A reduced area has been replanted in radiata with a strip adjoining the Glenomaru Stream being allowed to regenerate with natives that flourished under the pines. Although this block was beside a road, harvesting was complicated by the fact that most of the logs had to be hauled across the stream. Resource consent was obtained to install a temporary culvert to minimise damage to the waterway.

It was not until harvesting took place that I really appreciated the importance of placement of forests in relation to roads. Too many of us have planted away merrily without enough consideration for extraction issues such as provision for roading and skid sites and potential environment problems. Another lesson learnt from harvesting is the importance of insistence on contractors cleaning their gear before arrival on your property. Introduction of weeds like gorse and broom by this means is clearly unacceptable.

Recent planting

Planting in the last ten years has included a range of species with varying success. Douglas fir is growing well where not too exposed to strong winds. Redwoods are very site specific and growth rates are slow compared to further north. Sitka spruce, tried as a coastal alternative to Douglas fir, is doing well in small numbers but the spruce aphid looms as a threat. E. nitens as elsewhere grows prolifically in moderately fertile soils but their use, apart from being chipped, poses a few problems.

Planting in the last ten years has included a range of species with varying success. Douglas fir is growing well where not too exposed to strong winds. Redwoods are very site specific and growth rates are slow compared to further north. Sitka spruce, tried as a coastal alternative to Douglas fir, is doing well in small numbers but the spruce aphid looms as a threat. E. nitens as elsewhere grows prolifically in moderately fertile soils but their use, apart from being chipped, poses a few problems.

Of the natives, red beech, which does not occur naturally in this district, shows great promise with good form and growth rate. Can existing mixed podocarp native forests be managed for future timber extraction? Quite possibly, but not as successfully as with single species beech forests. The biggest hurdle is probably a mental one. For those used to 30 year rotation radiata the change to 200 year growing time is quite a leap.

Cypresses appear to be the best option in this area as an alternative to radiata. Canker has not been a significant problem here with our macrocarpa woodlots but recently we have used lusitanica and the nootkatensis hybrids as insurance against that threat.

Forest ownership

The retention of ownership of a tree block by my family until harvest obviously helped in the transfer of the property to Pam and myself. Forest ownership can also provide connection to the land for those family members who choose career paths other than active farming. With most of our larger plantings being on one block with a separate title, the splitting of this from the more productive farm land is an option.

There are still at least 60 hectares of land that I believe would be better planted in forest or allowed to revert to native forest. If or when this occurs will depend on future circumstances and availability of funds. There is no one template for the farm forestry model, as each farm and each landowner’s circumstances are different. But on our farm as on most throughout the country, farming and forestry are a natural mix.

Some farm statistics

- Total area 648 hectares

- Approximately 160 hectares cultivated

- 530 hectares purchased by the family in 1968

- Pam and Neil take over 1991 − 120 hectares added in 1996

- Stock wintered 2008 −2500 ewes, 400 hoggets, 100 cows, 90 calves, 130 deer

- Rainfall 1150 mm average

- Distance from coast12 km

- Altitude 50 to 450 metres

- Forest species:

- Radiata pine 90 hectares

- Douglas fir 11.5 hectares

- Cypress 6.5 hectares

- Other 6 hectares

- Native 130 hectares

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand