Manuka – a rapidly growing industry

Stuart Orme, New Zealand Tree Grower February 2017.

There was a time when the government paid farmers to clear manuka from their land. This article aims to help unravel some of the issues surrounding the source of New Zealand’s current liquid gold in the form of manuka honey.

Global demand for high value manuka products is increasing. New Zealand’s marginal land owners are well placed to take advantage of this, but developing a sustainable venture based on manuka is not necessarily straightforward. There are many practical and economic aspects to consider.

The market for manuka

A main product of the manuka tree Leptospermum scoparium is, of course, nectar which bees make into honey. New Zealand honey exports have experienced an exponential compound growth rate in excess of 20 per cent a year over the last 10 years. This makes it one of the fastest growing land-based industries, with the main driving factor being the increasing prices and demand for manuka honey.

With international acceptance and understanding of the medical opportunities which manuka has, there is a justifiable expectation that the growth limits are sustainable, if managed well, for some time yet. Prices for the honey range from $18 to over $130 a kilogram, depending on the activity rating of the honey.

The term activity as it relates to manuka is used to describe its antibacterial activity. In the case of manuka this varies in scale with higher rated activity levels being used for medicinal products and have an increased price premium in the marketplace.

There is a wide range of products that use manuka honey including −

- Food and beverages

- Skincare, soaps and lotions

- Natural health products such as throat lozenges and cough medicines

- Medicinal products used to treat wounds and infections with the special anti-bacterial quality of manuka honey which been scientifically proven, mainly due to the research efforts of the late Dr Peter Molan and associates.

Tea tree oil, also well known for its medicinal and therapeutic properties, can be derived from manuka foliage. An average manuka stand could potentially produce two to four tonnes a year per hectare on a bi-annual managed basis. Gross income can be in excess of $100 a tonne for foliage. If the foliage is harvested after flowering, a stand may take advantage of honey and oil crops.

Understanding the value chain

Most apiarists place hives on land owned by someone else and compensate the land owners by paying for the number of hives or on the amount of honey produced. Gone are the days where the beekeeper just dropped off a pot of honey as compensation. Examples of current agreements between the apiarist and landowner vary and may be based on a percentage of profit, a dollar value per kilogram of honey harvested, payment per hive for a season, or a mixture of all these arrangements.

If you are a land owner considering a working arrangement with a bee keeper it is wise to get independent advice before entering into any agreement. Once happy with the operator you are going to work with, it is best to give the bee keeper at least two years of access before judging the results because variations due to climate, flowering and eventual volume can be outside the apiarist’s control. When happy with the partnership, a long-term contract should then be considered which allows both sides to manage it and the joint returns to get the best result.

What is the best land use?

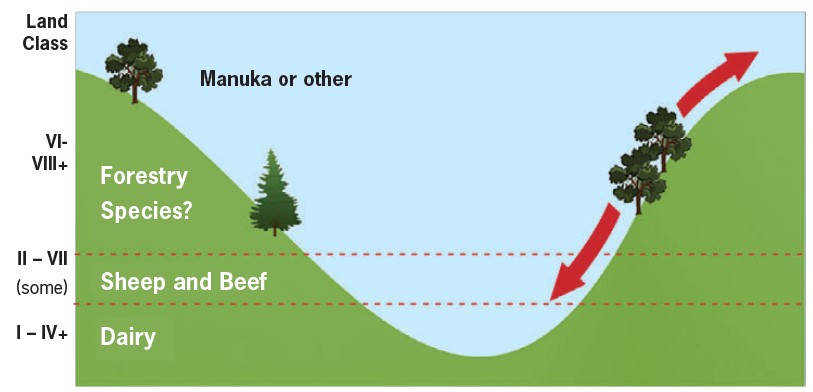

The underlying question for any production opportunity has to be what the best land use is. There will be a variety of solutions depending on land suitability and productivity, economic factors such as harvest costs and the distance to market, along with land owner aspirations.

The diagram on the left illustrates the perception that good land can and should be used to produce food. This then leads to the question of what the best marginal land use will be, which is invariably some form of vegetation. This article is not meant as an incentive to rush out and change current land use just because the return on investment looks better than the current options. It simply provides information for consideration of manuka as a crop, whether managed by stopping regular clearing of regenerating manuka, or by planting.

For best bee performance

Honey returns from manuka depend on the ability of bees to harvest the nectar and process it in the hive. The easier it is for the bee to operate the more likely the crop will be maximised. An ideal hive site may −

- Have a basin with an all-around aspect, with a sheltered hive location in the bottom by a water source that can be easily accessed and kept secure

- Have a native manuka population with high activity nearby, if a planted crop, which can add initial cash flow as young plants gets established. The native trees could be managed out and replaced with better material over time

- Not have any neighbouring bee hive operators or vegetation that might attract the bees elsewhere

- Be located in a position where bees need to fly over manuka to get to other more appealing sources of nectar further away, which will prompt the bees to choose the manuka.

The above factors are common to naturally regenerating manuka as well as to the planted manuka crop. The benefits and challenges for manuka as the vegetation of choice are summarised in the table below.

| Benefits | Challenges |

|---|---|

|

|

Existing resource

By far the most profitable option for a land owner is to receive income from an existing manuka resource on their property. With existing manuka there is an opportunity to effectively use it for manuka honey at no initial additional cost, other than perhaps establishing new access. This income can exist until the seedlings growing beneath the manuka break through the canopy and replace the manuka nurse crop.

Improved honey returns for an existing and emerging manuka are potentially available from −

- Active management by removing competing pollen sources

- Additional planting improved material of a higher activity rating

- Removing transition species to suspend the reversion process and retain the manuka crop on the site

- Planting support species which can feed bees outside the manuka season, which provides an opportunity for hives to stay on the site all year. This ensures a robust healthy bee population capable of maximum honey collection in what is normally the short time available to it.

A working example

The quality and quantity of honey available annually is not guaranteed, more so from a natural resource where the plant parentage will be variable and often exposed to honey dilution from other plants that attract bees.

Having a good relationship and trust in a competent beekeeper is invaluable as a commercial arrangement that benefits everyone can be developed.

The table below shows what is possible from a 100-hectare example using the following assumptions −

The land owner spends $100 a hectare in the first year on access establishment or upgrade and $40 a hectare each year on land costs such as rates and administration

- The site has 100 hives at one hive per hectare

- It models three different activity levels and associated dollars per kilogram of honey, currently or close to those being paid in the market

- Hive production averages 25 kg a year over a 30-year period which is below the average production noted by the Ministry for Primary Industries of 31.7 kg per hive, and possibly well below or above any New Zealand site at any given time

- The dollars per hive back to the land owner and the internal rate of return from that land use investment is based on three different percentage shares of gross hive revenue.

The figures in red show where the bee keeper has most probably lost money on the arrangement, which in the long term is not good for the land owner. It becomes evident that with trust and good records there is room to come to an arrangement which rewards a land owner for managing a native crop of manuka to maximum production.

There is also strong evidence to support planting manuka as a forest crop for honey, carbon and biodiversity. This is especially the case when compared to internal rates of return of between two and four per cent for the average sheep and beef and dairy farm, excluding current market returns.

Planted manuka

Costs associated with planting manuka are higher than managing an existing resource. Therefore, the expected internal rates of return available will be lower, but will still appear to be better than mainstream returns if looking for an alternative or supplementary land use. It costs the same amount of effort and resources to establish a manuka crop with a poor activity rating for the honey produced as it does a high activity crop.

| Manuka activity | Dollars per kilogram | 10 per cent share | 20 per cent share | 30 per cent share | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dollars per hive | Internal rate of return | Dollars per hive | Internal rate of return | Dollars per hive | Internal rate of return | ||

| 5 | $18 | $5 | 0.45% | $45 | 36% | $90 | 68% |

| 10 | $35 | $43 | 34% | $130 | 96% | $218 | 159% |

| 15 | $55 | $93 | 70% | $230 | 168% | $368 | 266% |

| Manuka activity | Dollars per kilogram | 10 per cent share | 20 per cent share | 30 per cent share | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dollars per hive | Internal rate of return | Dollars per hive | Internal rate of return | Dollars per hive | Internal rate of return | ||

| 5 | $18 | $5 | -13.8% | $50 | -4.3% | $95 | -1.15% |

| 10 | $35 | $48 | -4.5% | $135 | 0.66% | $223 | 3.39% |

| 15 | $55 | $98 | -1.02% | $235 | 3.71% | $373 | 6.45% |

| 20 | $95 | $198 | 2.72% | $435 | 7.41% | $673 | 10.27% |

Proven genetics are therefore important when selecting which manuka crop to plant.

Costs can range between $1,650 a hectare to $2,500 a hectare depending on −

- Land preparation

- Pest control which is critical if goats are present

- Tree stock purchased

- Planting costs which are normally not very different from those of planting normal forestry species

- Weed control

- Pest and weed control to get the crop successfully established.

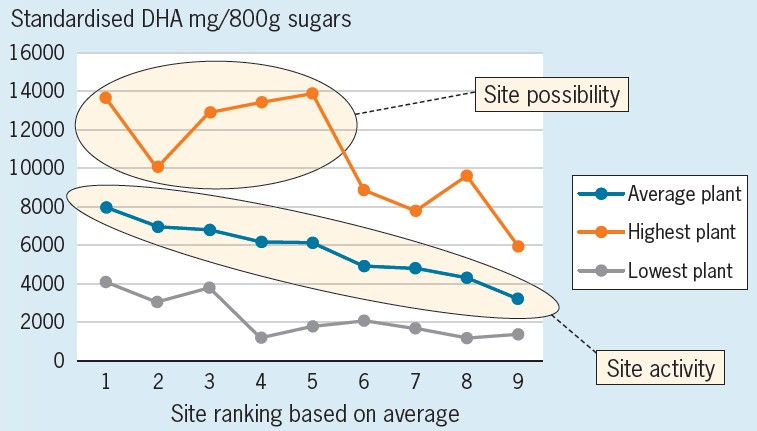

The diagram summarises some work that Midlands Apiaries completed recently showing the range of activity in several manuka populations.

The main point to understand from the diagram is that the current manuka honey activity is made up of the average activity in the manuka crop, less whatever contamination comes into the crop by way of foreign nectar from plants competing for the attention of the bees. By establishing plants which have a history of high activity, or the offspring of them, in the right site, a honey crop with a high activity is more likely to be produced.

The table at the top of the page takes the same examples as the first table and assumes an additional $2,000 a hectare to plant a manuka crop which does not start producing in full for 10 years. Given what a good plant breeding programme is capable of, it also models the return from a higher activity level that currently commands a top price in New Zealand from the hive. The figures in red again show that the landowner is out of pocket. If we add potential carbon returns, assuming $15 a unit from the Emissions Trading Scheme based on the carbon sequestration tables, the internal rate of return increase from minus 13.8 per cent in the first example to plus 3.2 per cent. In the last example it rises from 10.27 per cent to 12.5 per cent. This is an average carbon income, assuming $15 a unit, of $142 a hectare each year once growth variances are accounted for. Incidentally, some manuka blocks we have measured exceed the Ministry for Primary Industries indigenous carbon sequestration tables for their region.

Summary

Some land owners are spending upwards of $2,000 a hectare to clear manuka, apply fertiliser and try to bring back naturally reverting land into grass production. Others may already have sectioned off similar land which is receiving a diminishing grazing return, but a climbing carbon and honey return. Neither method is necessarily wrong, but the values obtained in the environmental, biodiversity and long-term economic sustainability areas will be quite different.

What the best land use is will be different for everyone and more than likely the best option will be a matrix of possibilities. However, the common thread is that whatever the best use is – whether driven by history, core skills, aspiration or cash flow – the decisions around it need to be made and reviewed from time-to-time in an informed manner and with a medium to long-term view.

With a growing community expectation to improve environmental standards, planting the right species on the right land has gained acceptance within the agricultural community. It is further supported by agencies which provide funding, allowing landowners to make considered land use changes. At one time in the past, around 66 cents in the dollar were available to clear scrub and indigenous forest for pasture. Now up to $1,500 a hectare is available to re-establish it.

Stuart Orme is a Registered Forestry Consultant based in Masterton.

Farm Forestry New Zealand

Farm Forestry New Zealand